SIX LEGS GOOD: INSECTS IN ART

For every person on earth, there are over a billion insects. It seems only reasonable, then, that they should feature significantly in our art. They have done so in three ways: first and most frequently, as a subject; second as a material; and third as collaborators in the making. The range of work is considerable, so this article focuses on a representative cross-section from each of those categories.

Depictions of insects

Insect depictions started, of course, with the ancients. Museums such as the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and The British Museum in London, hold wonderful scarabs from Ancient Egypt. But we’ll fast forward to the Enlightenment, when the emerging scientific paradigm led to the picturing of insects as adjuncts to discovery and classification. That might be added to the depiction of insects simply because they were there in the landscape, or for their metaphorical attributes.

Insects often appear in Golden Age still life paintings of flowers, adding an extra element through which artists can demonstrate their skill. They may also symbolise the interconnectedness of life, the teeming variety of God’s design, or be reminders of death – being associated with decay. And specific insects have their own associations: flies stand for the brevity of life, crawling insects – beetles and caterpillars – symbolise earthy life full of sin; butterflies and dragonflies represent transformation and – in their freedom of flight – the soul.

Jan van Kessel the Elder (1626-79) had the ultimate artistic heritage: his grandfather was Jan Brueghel the Elder, and David Teniers the Younger was his uncle. He specialised in meticulous studies of insects and flowers, typically in somewhat artificial arrangements that recall the ‘cabinets of curiosities’ that were fashionable in Renaissance Europe – collections of natural objects and artworks that were regarded as a microcosm of the world. As such, the insects are foregrounded in contrast to their supporting role in the floral still life. The apparent placement on vellum, rather than in nature, and combination of various viewpoints add to the sense of specimens laid out for our inspection. The invention of the microscope – generally credited to Dutch spectacle makers Hans and Zacharias Janssen and Hans Lippershey, around 1590 – was an important factor in the realism achieved, albeit often indirectly: typically still life painters would have worked from secondary sources, and van Kessel used a mixture of illustrations and scientific diagrams.

Some 17th century painters did work from life and were also important in the development of entomology as a science. Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717) grew up in Frankfurt, where she took an early interest in insects and was raising silkworms by thirteen. That, together with her father being an artist, led her to rear insects in order to observe and record their metamorphosis on their plant host and through their entire life cycle. Merian was the first to write about the significant relationship between various insects and plants — a cornerstone of modern ecology – and provided evidence against the prevalent contemporary belief in spontaneous generation. She moved to Amsterdam in 1691 onwards, where she published books of her findings. In 1699, she was the first European woman to independently go on a scientific expedition in South America, leading to her account of the insects of Suriname, then a Dutch colony. In 1705, she published her seminal Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium, in Dutch and Latin, including 60 illustrations depicting tropical insects, plants and animals in their full life cycle and their food plants. Following her return to Amsterdam, she continued to breed, study and document European caterpillars and flies. Her images were used by Linnaeus and others to identify many new species, and in recent years, Merian’s status as a scientific pioneer, trailblazing woman, and significant artist has risen.

The appearance of insects in compositions primarily focused on other subjects speaks of a style concerned with detail. For that reason, their frequency declines in the 18th century; and in the 19th the Impressionists rarely feature them, though the Pre-Raphaelites often do (i).

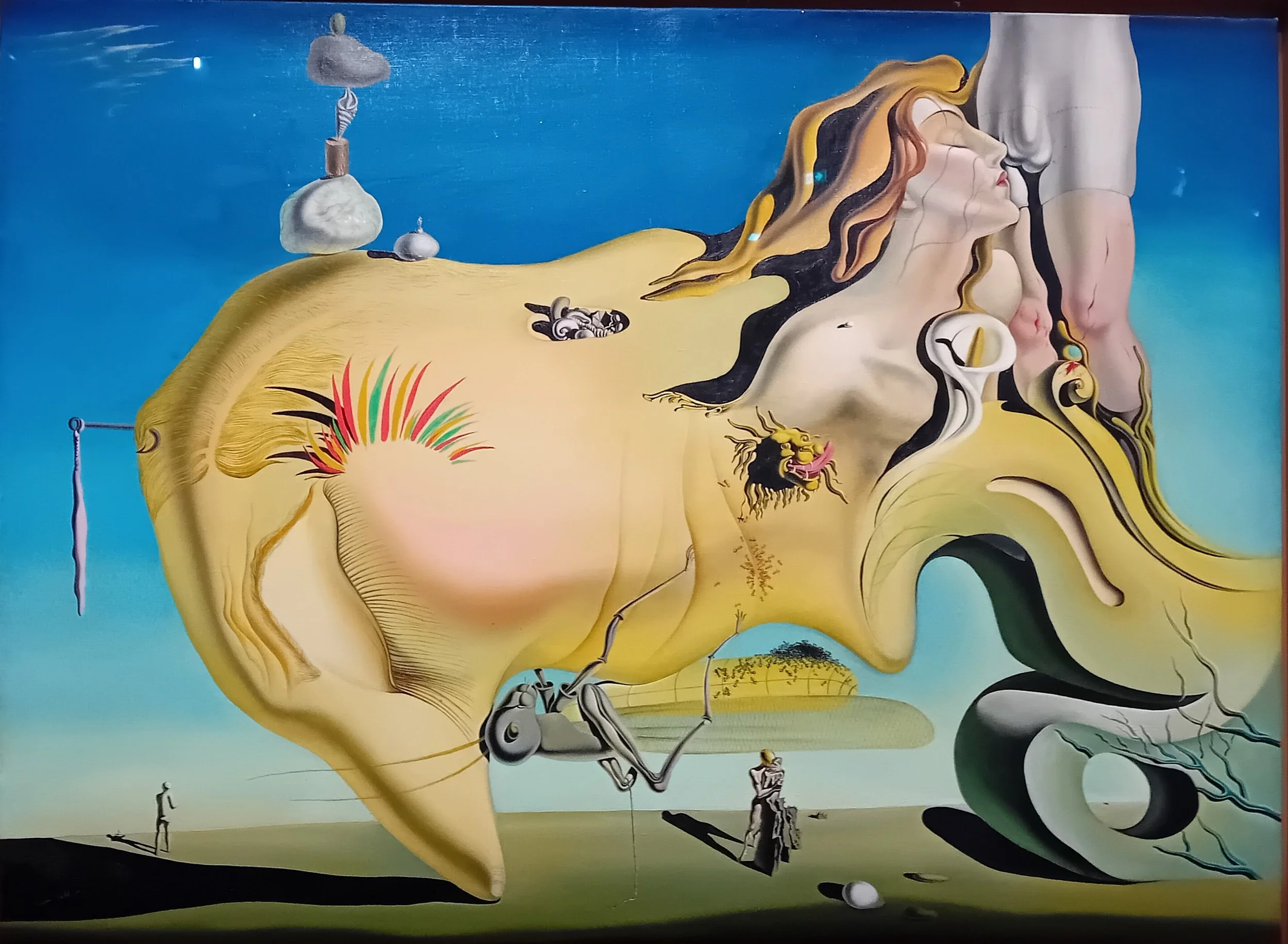

The surrealists were attracted to insects, mainly for their strangeness and psychological potential. That could lead to a lack of realism: insects with human heads, for example, or Dalí’s tendency to depict grasshoppers as having only four legs (see, for example, The Great Masturbator, 1929). Dalí’s favourite insects, though, were ants, which appear in some fifty of his paintings and in the film Un Chien Andalou. His autobiography (ii) suggests the source of the mixture of fear and fascination they carried for him: ‘The next morning a frightful spectacle awaited me. When I reached the back of the wash-house, I found the glass over-turned, the ladybugs gone and the bat, though still half-alive, bristling with frenzied ants, its tortured little face exposing tiny teeth like an old woman's … With a lightening movement I picked up the bat, crawling with ants, and lifted it to my mouth, moved by an insurmountable feeling of pity …’

Armies of ants can appear pretty-much infinite, and MC Escher sets ants in an infinite context for them in his famous ‘Möbius strip’ series, as eight red ants track one another around a figure eight which twists back on itself. Escher often used insects in his bafflingly logical compositions, and even expanded their variety in 1951: he explained that the six-limbed Pedalternorotandomovens Centroculatus Articulosus (curl-up) ‘came into existence (spontaneous generation), because of the absence, in nature, of wheel shaped, living creatures with the ability to roll themselves forward’. The Latin name might be translated as ‘moves by rotating alternate feet, has central eyes and is full of articulations’.

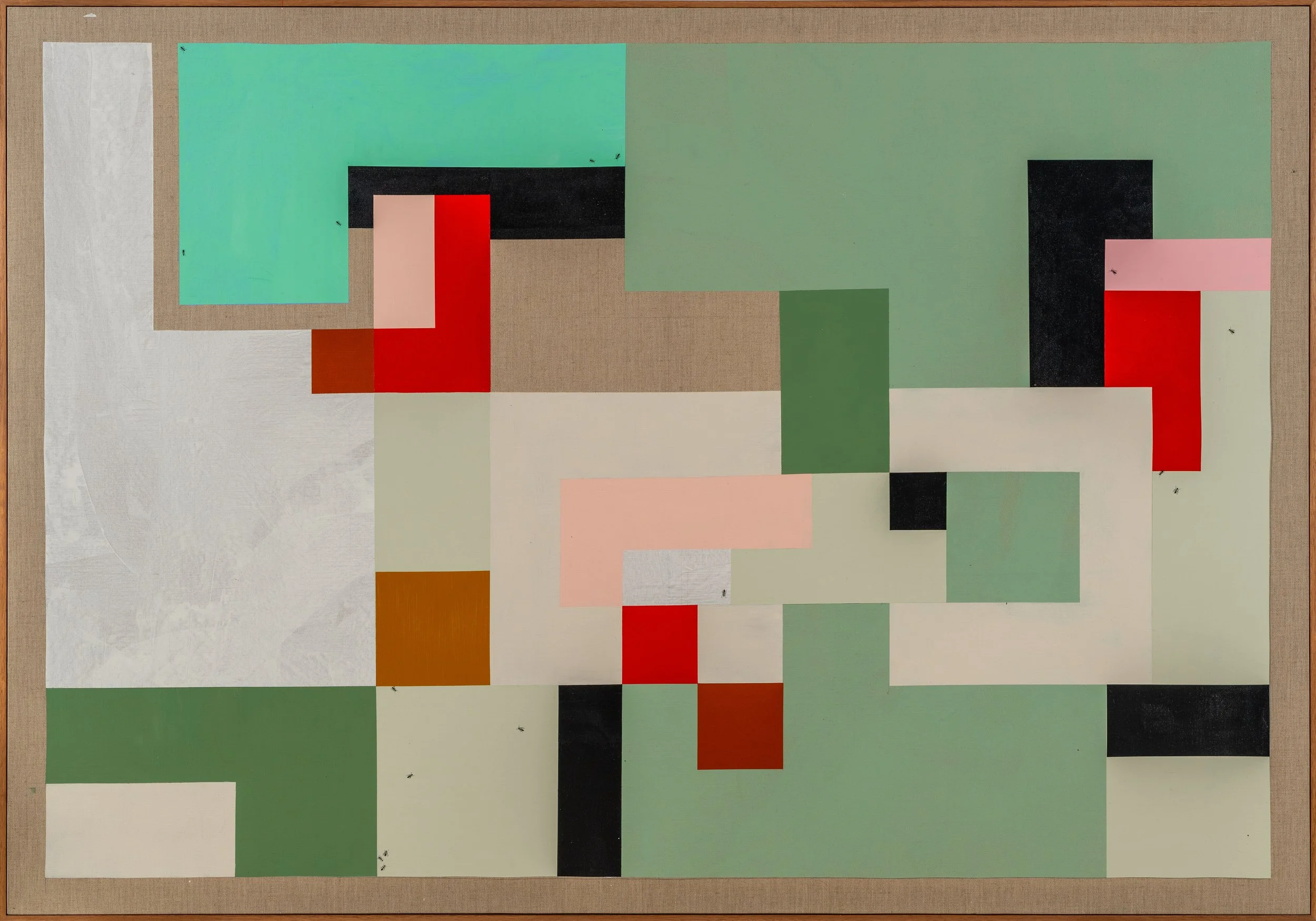

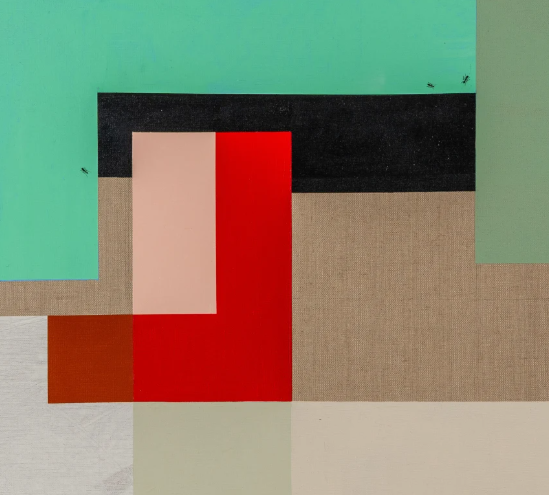

A more recent take on the ants casts them as disruptors in what look like abstract paintings. Palestinian painter Ruba Salameh evokes aerial views of a city or electronic circuit boards using a visual language that draws on Constructivism, Bauhaus and Minimalism. Carmel is perhaps most reminiscent of Ben Nicholson. But she includes small black dots, which on close inspection are revealed as depictions of ants. Some gather around shapes as if to carry them away, others seem to be stuck in corners or forced along paths. The addition of the ants to the pictures suggests a meeting of the man-made and organic, the disruption of a pure surface, and alludes to the resilience of communities suffering oppression.

The somewhat anthropomorphic praying mantis is another favourite of the Surrealists, André Masson and Max Ernst in particular. Ernst first came close to mantids in 1923-24 when he stayed with the movement’s leading poet, Paul Éluard, who was raising them. And Ernst will have read the writings of the surrealist biologist Roger Caillois: his The Praying Mantis: From Biology to Psychoanalysis (1934), identifies an innate lyricism in the mantis that breaches the barrier between the human and the non-human. The attraction for artists was undoubtedly the notorious cannibalism of the female during mating, making the mantis an ideal cipher for exploring the conjunctions of desire and fear, creation and death. And it fitted in with Freud’s theory that the ‘vagina dentate’ – with teeth – captured the fear of castration that he argued all boys feel upon first seeing female genitalia. That adds an edge to the mantis’ appearance in Ernst’s The Joy of Life, 1936, for example. It's not true, incidentally, that the females always devour their mates: only a few of the 180 species do so, and the incidence varies. Yet the frequency is sufficient to make us wonder what the evolutionary reason might be. Some biologists say it's simply hunger: the females, which are much larger, may be unable to resist a male meal that's so tempting and so vulnerable, and research suggests that well fed females are less likely to eat their mate. But it may also be that the sex act is protracted when the female gets caught up in chewing her partner, increasing the odds he will fertilize her eggs — the male can continue to engage in sex after his head has been devoured, as a ganglion in the abdomen controls the motions of copulation (iii). That may, then, provide an evolutionary advantage to being consumed – although, on the down side, his chances of mating with other females are ended.

Sarah Gillespie is known for her fabulously detailed mezzotints of the moths she finds in her Devon garden. The mezzotint, to take a detour into the 17th century invention of the German soldier-artist Ludwig von Siegen, is a labour intensive form of intaglio that generates half-tones by roughening a metal plate with thousands of little dots made by the small teeth of a metal ‘rocker’, so that tiny pits in the plate retain the ink when the face of the plate is wiped clean. Gillespie has written of how art can seem ‘above engaging with anything so dreary as a dying planet’, in which context she sees paying close attention as an act of rebellion (iv), given that ‘in our brightly lit, self-absorbed and busy lives’ she believes it is ‘above all our attention to the lives of our fellow creatures that has slept’. Over 60 British moths have become extinct over the past century, and their total numbers have fallen by a third. They tend, says Gillespie, to be ‘unseen in the dark and dismissed as ‘dull’ in favour of their flashier, diurnal cousins, the butterflies’, but are in fact more numerous and more varied, are a major part of our biodiversity and hold vital roles in the wildlife ecosystem. For example, their caterpillars are vital to feeding the chicks of many birds. Mezzotint provided a labour of love through which to pay that homage of attention, and ‘the gradual drawing forth of the moth from the darkness seemed a perfect matching of method to subject’.

The Peppered Moth, to take another detour, is often known as ‘Darwin’s Moth’, as he identified it as a key example of natural selection. Darwin noted how the naturally occurring genetic mutation of black, rather than pale peppery, wings became commoner in urban areas because they were better camouflaged in the sooty environment resulting from the industrial revolution. Darker wings made predation less likely, because pollution had both killed off the lichen and made walls and trees trunks darker.

Sticking to moths, the Starn brothers, featured in our online Visual Fine Arts section, find a way to pick up materially on their characteristics in the series ‘Attracted to Light’. The title suggest behaviour typically attributed to moths, but might also stand for both the lure and the fundamental process of photography. The prints are both tattered and abraded, not from age so much as to make a reference to the double fragility of moths. First, as their wings can tear easily from even the slightest touch. And second as their wings are covered in a mosaic of microscopic scales that snap into individual pocket-like slots to stay attached. They are, nonetheless, easily lost: the scales are as fine as dust, and after touching a moth’s wing a dust-like layer will often be left on a person’s hand. The good news is that moths can continue to fly with reduced wings, and despite losing some scales – even though they do improve the lift to drag ratio.

Scales have other functions (v): they can act as camouflage; can help attract a mate; and may interfere with light to make it harder for predators to detect them, and possibly interfere with echolocation, too. They can also act as insulation. That’s why moths tend to have thicker scale layers than butterflies: moths – being mainly nocturnal – can’t warm up in the rays of the sun, so they need extra insulation.

None of that, however, explains why it might be helpful to lose the scales so easily. The answer lies in the common scenario of a moth flying into a spider’s web. Thomas Eisner (vi) tested various insects by dropping them onto a web, and found that only moths were consistently able to escape, fluttering vigorously but sliding over and off the web without sticking – while leaving scales behind. According to Eisner (vii) ‘they all left impact marks on the webs where scales became detached to the viscid strands. Moth scars, we came to call such tell-tale sites, and soon learned that they were common.’

When shown at Tate Modern, Petrit Halilaj’s group of giant moth costumes was suspended at various heights and illuminated by custom flickering lights. The artist performs in these costumes: having been a bird and a dog, he has recently favoured moths as an animal persona. Woven into their construction is a strong sense of familial history and memory. Halilaj worked with his mother to create the sculptures out of materials including Kosovar fabrics and Dyshek carpets. During this process, the two discussed Halilaj’s childhood memories. When he was younger, Halilaj would chase moths around the light bulbs in his family house in Kostërrc – a home which was destroyed during the Kosovo War (1998-9). As a moth he can forget that trauma.

But are moths attracted to light bulbs? The latest scientific research suggests not: it’s more that lights trap any moths that happen to fly past. According to a study (viii) employing high-resolution motion capture and stereo-videography to reconstruct the 3D kinematics of insect flights around artificial lights, moths do not steer directly toward the light. Instead, they turn their dorsum toward the light, generating flight bouts perpendicular to the source. Under natural sky light, tilting the dorsum towards the brightest visual hemisphere helps maintain proper flight attitude and control – an evolutionary advantage. Near artificial sources, however, this response can produce continuous steering around the light and trap a moth. Dr Sam Fabian, an entomologist at Imperial College London, explains that ‘If the light’s above them, they might start orbiting it, but if it’s behind them, they start tilting backwards and that can cause them to climb up and up until they stall. More dramatic is when they fly directly over a light. They flip themselves upside down and that can lead to crashes. It really suggests that the moth is confused as to which way is up.’

Alison Turnbull has also studied moths closely, indeed she started with the evolutionary story of the Peppered Moth depicted by Gillespie above, being interested in the parallels between such variations driven by mimicry and the processes of mapping, transcription and conversion that characterise her art. Here, though, we have Turnbull’s transcription of the DNA barcode of a species of Morpho butterfly. As she explains, ‘the iridescent blue butterfly is found in Latin American rainforests. I saw them initially in the Natural History Museum’s collections and subsequently in the Colombian Pacific rainforest. I wanted to translate the barcode in watercolour – where the vagaries of the hand-made are inescapable – so the image would become more tremulous, less fixed.’ Here, then, the coding that replaces the traditional reliance on visual cues becomes the visual cue. Such DNA barcoding, the use of short, standardised genomic regions to facilitate species identification and discovery, has revolutionised the study of biodiversity, aiding both specimen identification and species discovery, while also revealing eco-evolutionary processes.

Czech artist Anna Hulačová approaches environmental issues from an unusual perspective, explaining that bees are her favourite subject because pollinators are an indicator of the cleanliness of the environment. It’s telling, she observes, that ‘the city is currently a cleaner environment than the countryside, which is surrounded by fields treated with pesticides’: consequently, beekeepers who have apiaries on the roofs of townhouses observe that urban honey often has a better chemical composition than rural honey’. It is, however, ‘fantastic how bees are able to adapt to changing conditions – there is a unique evolutionary mechanism that works in them, for example in terms of body transformation in reaction to the parasite varroa mite. I imagine the toxic landscape then, as a strange inhospitable universe in which surviving animals have to mutate or transform to survive. Like aliens in their own alienated universe – the landscape. The insect world is also alien to us in many ways, and I enjoy the idea of mutant bees reminiscent of the aliens from the covers of mystery sci-fi magazines in the ’90s’. That led her to the invocation ‘Alien bees, save us, please!’ She sees that as ‘a fanatical prayer to aliens who could save the planet for us, because we don’t believe we are capable of doing anything about it.’

A logical end to the section on representations of insects is the giant fly that settled on a swirl of cherry-topped fake whipped cream on Trafalgar Square’s fourth plinth in 2020-22. Heather Phillipson describes this particular version of a Knickerbocker Glory as apocalyptic: riffing on Trafalgar Square as ‘the centre of hubris and data collection’, she added a drone that inverted the usual collection of information by broadcasting the sculpture’s view of its surroundings. The implication of impending collapse is picked up in the title: Esther Leslie has suggested (ix) that The End may evoke the climate emergency, the end of the welfare state, the death of democracy, the murder of truth, the end of privacy. What it is unlikely to presage is the end of flies: they’ve made it through millions of years already and can survive harsh environments. Take radiation: it is measured in units called grays. Doses as low as 3-6 grays are fatal to humans. Some cockroaches have survived 900 grays. But fruit flies have survived doses of 1,600 grays (x). They are, moreover, fast to reproduce, agile avoiders of attack, and can get by with very little. Outlasting us will be no problem.

Insects as material

One step on, perhaps, from depicting insects is actually featuring them physically in the work. The longest-established practice of that type is in the form of paint: carmine red is made from the cochineal, a tiny cactus-loving scale insect of the suborder Sternorrhyncha that produces carminic acid to deter predators. The insects are brushed off the pads of prickly pears, dried, the acid extracted, then mixed with aluminium or calcium salts to make the carmine dye, also known as cochineal. That’s traditional enough. One might, on the other hand, assume that collaging whole insects to paintings would be a purely modern trend. Yet, not so: the 17th century Dutch artist Melchior d'Hondecoeter specialised in painting natural scenes as realistically as possible, and while he was particularly noted for his birds, a lizard and butterflies also appear in this evocation of a forest floor. If the butterflies look convincing, that is largely down to his attaching real butterfly wings to the canvas.

Fast forward to the 1950’s, and Jean Dubuffet’s application of butterfly wings to his paintings was differently motivated: their patterns were incorporated into abstracted compositions evoking the life of the earth, and fitted within his philosophy of his ‘Art Brut’: challenging traditional ideas of beauty by taking the ‘outsider’ art of children and the insane as exemplars, and using such unorthodox materials as cement, plaster, tar, asphalt – and butterfly wings. Consistent with his challenging of aesthetic conventions, Dubuffet dismembered the butterflies brutally, tearing the wings apart and randomly distributing their fragmentary remains.

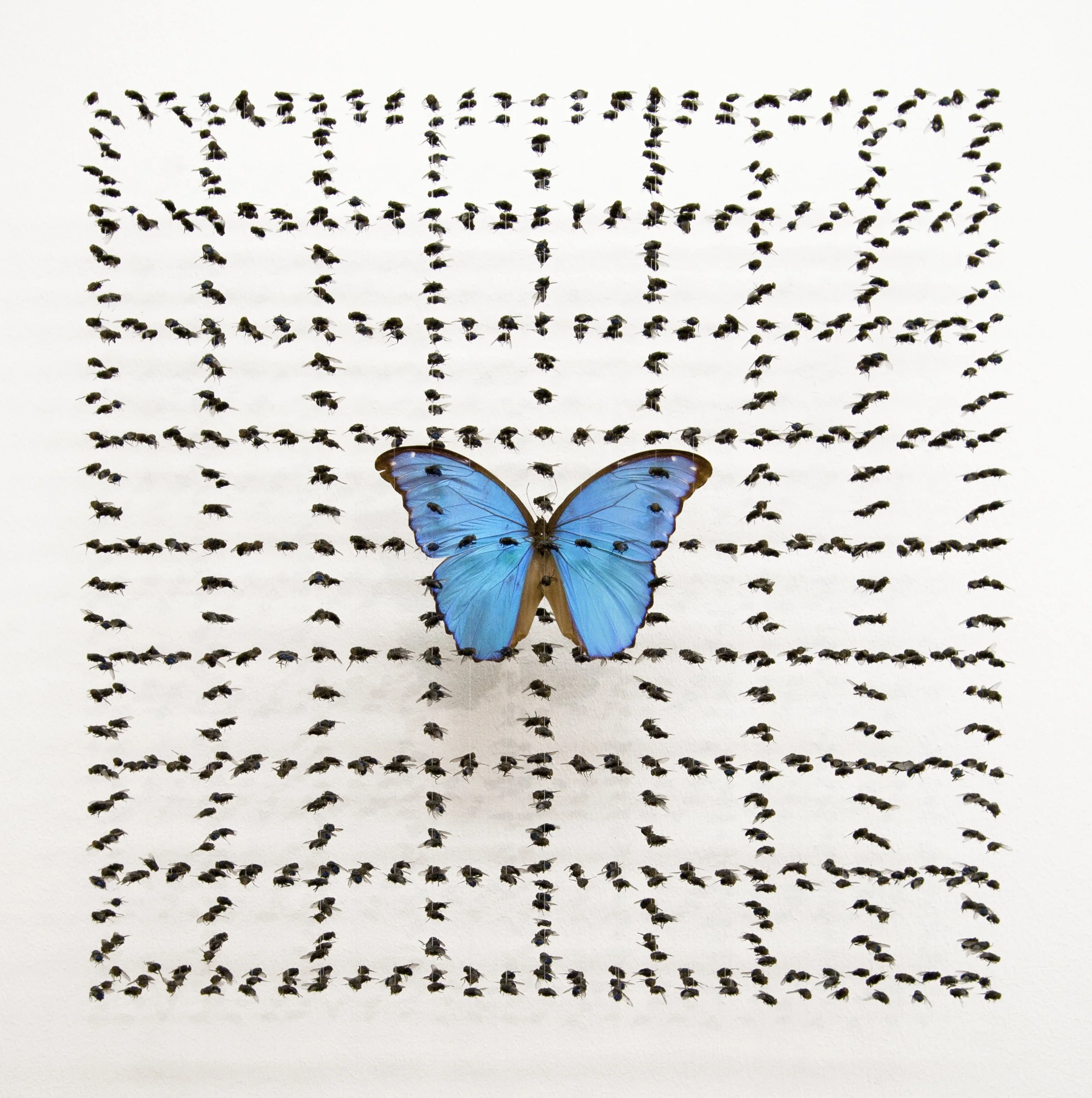

There was, then, plenty of precedent for Damien Hirst’s more famous use of butterflies. He has employed them in two distinct manners. First, as in In and Out of Love (1991), in a live setting, with the butterflies allowed to settle on paintings. That leads to works in which the insects are distributed on the surface, remaining whole, and according to natural chance. Second, highly orchestrated and patterned combinations of wings that take on something of the aura of stained glass windows – not a coincidence, as the connection between butterfly and soul is evidently in Hirst’s mind in such works as Disintegration – The Crown of Life, 2006.

One could argue, however, that the Hirst uses the humbler, and despised, common fly more powerfully. He has made dense black surfaces out of their dark massed bodies to gloweringly menacing effect, and they are central to A Thousand Years, 1990, which many consider to be his most impressive work. The life cycle of flies takes place in an enclosed glass and steel structure that spans over four meters. Maggots metamorphose into flies within the confines of the transparent chamber, and the flies are provided with a cow’s head as sustenance, and also an Insect-O-Cutor. The means of life and death are made visible within the artificial ecosystem, making for a visceral update on the Vanitas theme.

It makes sense that the Belgian artist Jan Fabre is fascinated by beetles: he is the great-grandson of the famous entomologist Jean Henri Fabre. As Jan explains, his family ‘had a lot of old publications, manuscripts, drawings. I remember the first time I saw them, I was seventeen or eighteen years old and it influenced me a lot. Later, I built my first laboratorium, The Nose / Noselaboratory (1978 – 1979), in my parent’s garden and I was sitting inside at a small table drawing, using my microscope, digging up worms, catching flies; ripping off wings of flies and trying them on the worms. I felt like Dr Frankenstein doing these experiments’ (xi). Fabre has made many works using buprestid beetles as materials, effectively ‘painting’ with their colour. Fabre appreciates the so-called ‘jewel scarabs’ for their beauty, memory, and ability to process information, which he says has enabled them to survive millions of years. As he says ‘Scarabaeus have an outer skeleton. That’s the reason why this insect survived a couple of million years and of course thinking about exoskeleton is thinking about creating a new skin, a new armour for humans … creating a new kind of protection. From the moment humans have an outer skeleton, you can’t hurt them anymore, you can’t wound them and you go away from the stigmata of Christ’. He used 1.6 million of their iridescent emerald-like shells to encrust his work for a ceiling in Brussels’ Palais Royal (Heaven of Delight, 2002). Skull with Magpie sees a more modest usage form a skull that ratchets up the Vanitas theme while giving the jaws of death a glamorous allure.

Two British artists – Tessa Farmer and Claire Morgan – have worked extensively with insects, building them into all manner of sculptural scenarios. Morgan featured in the Seisma exhibition ‘Seismic: Art meets Science’ and in our 2023 print edition ‘03: Entomology’.

Farmer, featured in our Kafka Series online, turns flies into armies of fairies in such installations as Swarming Fever, 2021. Her matter of fact description cannot disguise that it is rather extraordinary: ‘fairies, riding in weaponised skullships, flown by enslaved bees, beetles and butterflies are chasing and hunting a fleeing bird. A swarm of one hundred bumblebees spews from the main ship which is constructed from a small caiman skull, crab claws, snake ribs, mouse bones, wormshells, shed snake skin and coral.’ The fairies are sinister and sophisticated – as is consistent with their medieval origins as myth, rather than the adonised version encountered in recent times; or with the behaviour of the parasitoid wasps – also studied by Farmer – which lay their eggs in the bodies of others. Perhaps they are some sort of evolutionary link between insect and human. Indeed, while the Boschian dramas mimic the enthralling malevolence of hedgerows using their own inhabitants, Farmer does see them as making a case for insects: they are often maligned and misunderstood, she says, but ‘are actually an essential part of the ecosystem, providing important pollination, pest control, and decomposition services.’ Ignorance of that ‘is perhaps symptomatic of our increasing disconnection with the natural world’.

What those examples have in common is that the insects are dead. The use of living insects as a material is rarer, the most striking example being Pierre Huyghe’s Untitled (Reclining female nude), 2012, in which a concrete figure sports a beehive structure as its head, making it a living swarm of bees coming and going. As the work’s owner, New York’s MoMA, explains ‘the living beehive serves as the nude’s head, but also, by extension, her brain. The collective thought processes of bees – their ‘hive mentality’ – have long been studied in relation to human political and social organisation. Untitled (Reclining female nude) explores these affinities and emphasises the ancient, symbiotic relationship between humans and honeybees, which, in building their hive, collaborate in the creation of the sculpture.’

Insects as artists

Can insects make art? Not, perhaps, without human help, but that unlocks a number of collaborative possibilities. Indeed, Steve Kutcher, who uses insects as living paintbrushes, says ‘I have to take good care of them. After all, they are artists!’ We’ll start with bees, then move on to ants before arriving at Kutcher, who uses many different insects. Other examples might include Neri Oxman’s pavilions made by silkworms, or – stretching more broadly into arthropods – Tomás Saraceno’s employment of spiders.

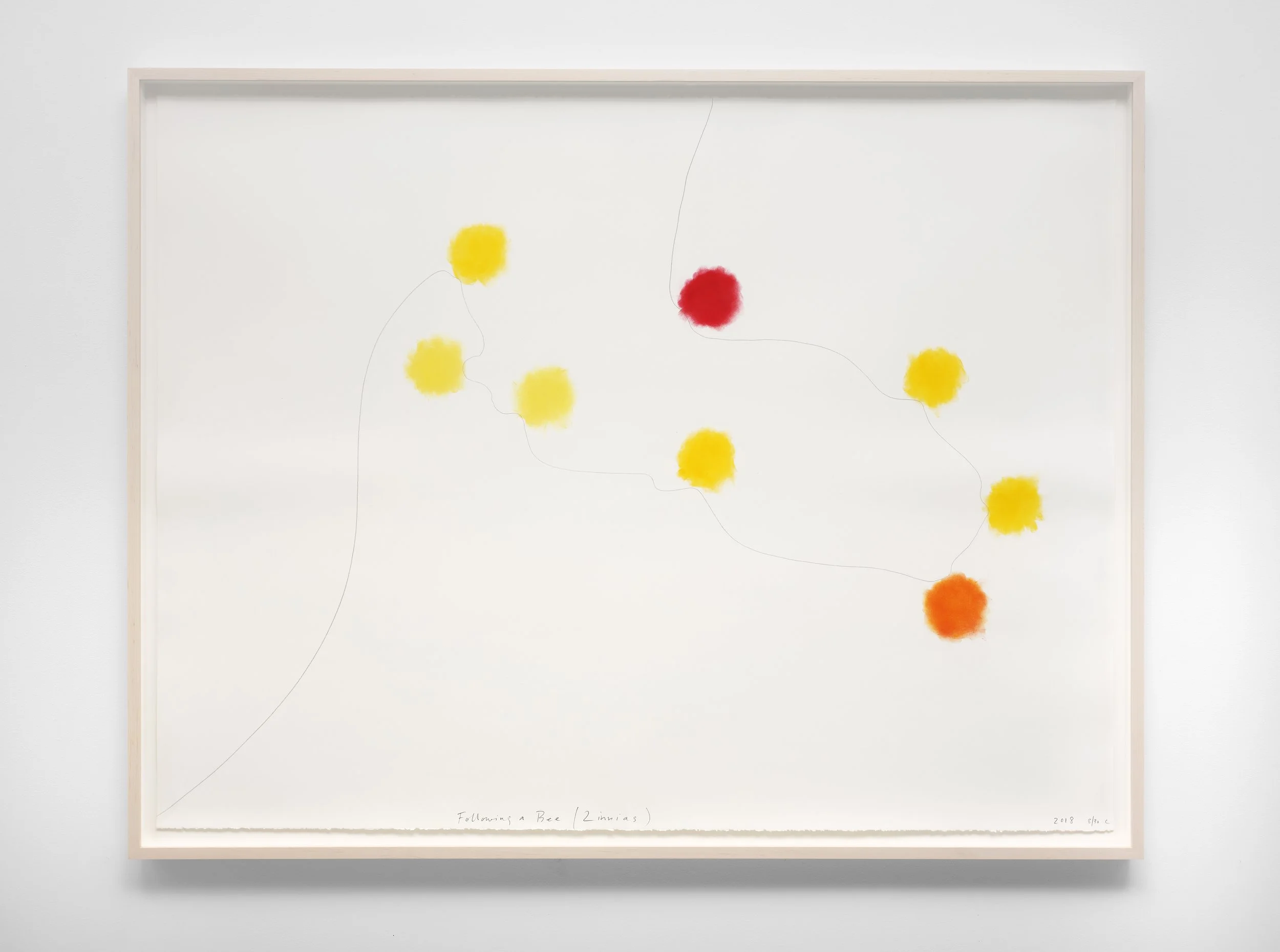

American artist Spencer Finch enjoys observing bees, and has set up his garden as a ‘laboratory for making art’ so that they might be said to make drawings for him. Every summer Finch grows a bed of several hundred zinnias. Each morning, he photographs them so he knows where the blooms are, then sits up on a ladder with a print-out of that on acetate. When a bee arrives, he follows the line of its flight. Once it stops to pollinate, he marks on the drawing where it stopped, repeating the process as the bee flies on from flower to flower – typically for around five minutes, stopping up to twenty times before it leaves the zinnias. He places the acetate on an overhead projector to transfer the lines, then matches the dozen or so colours of the flowers in his patch to the colour of his pastel.

Finch learns about bee behaviour along the way. He’s found that they move extremely unpredictably: for example some visit only a couple of blooms before leaving, and one bee will ignore flowers that the next bee chooses. And ‘sometimes they’ll stop for hours on one flower’, he says, ‘I’m not sure why, maybe they just need a break. I cut my losses in those cases and follow a different bee’.

Rivane Neuenschwander, 'Quarta-Feira de Cinzas / Epilogue', 2006. DVD projection, made in collaboration with Cao Guimares, Installation dimensions variable.

Running time: 5 minutes, 44 seconds. Copyright Rivane Neuenschwander and Cao Guimarães.

How about ants as — unwitting — performance artists? That is one way of looking at Quarta-Feira de Cinzas / Epilogue, 2006. The six minute loop, by the Brazilian artist Rivane Neuenschwander in collaboration with Cao Guimarães, shows red and black ants carrying coloured confetti across the floor of the Brazilian rainforest. The artists saturated the confetti discs in pork fat and sugar to attract the ants. The title is Portuguese for Ash Wednesday — the start of Lent and the last day of the Carnival festival, in which confetti is thrown. Neuenschwander has described the work as an attempt to ‘capture the mood of the end of the festival, when there is a certain melancholy after the days of madness and excess’; and said that what fascinates her in working with ants is ‘the collaboration between chance and control’ (xii).

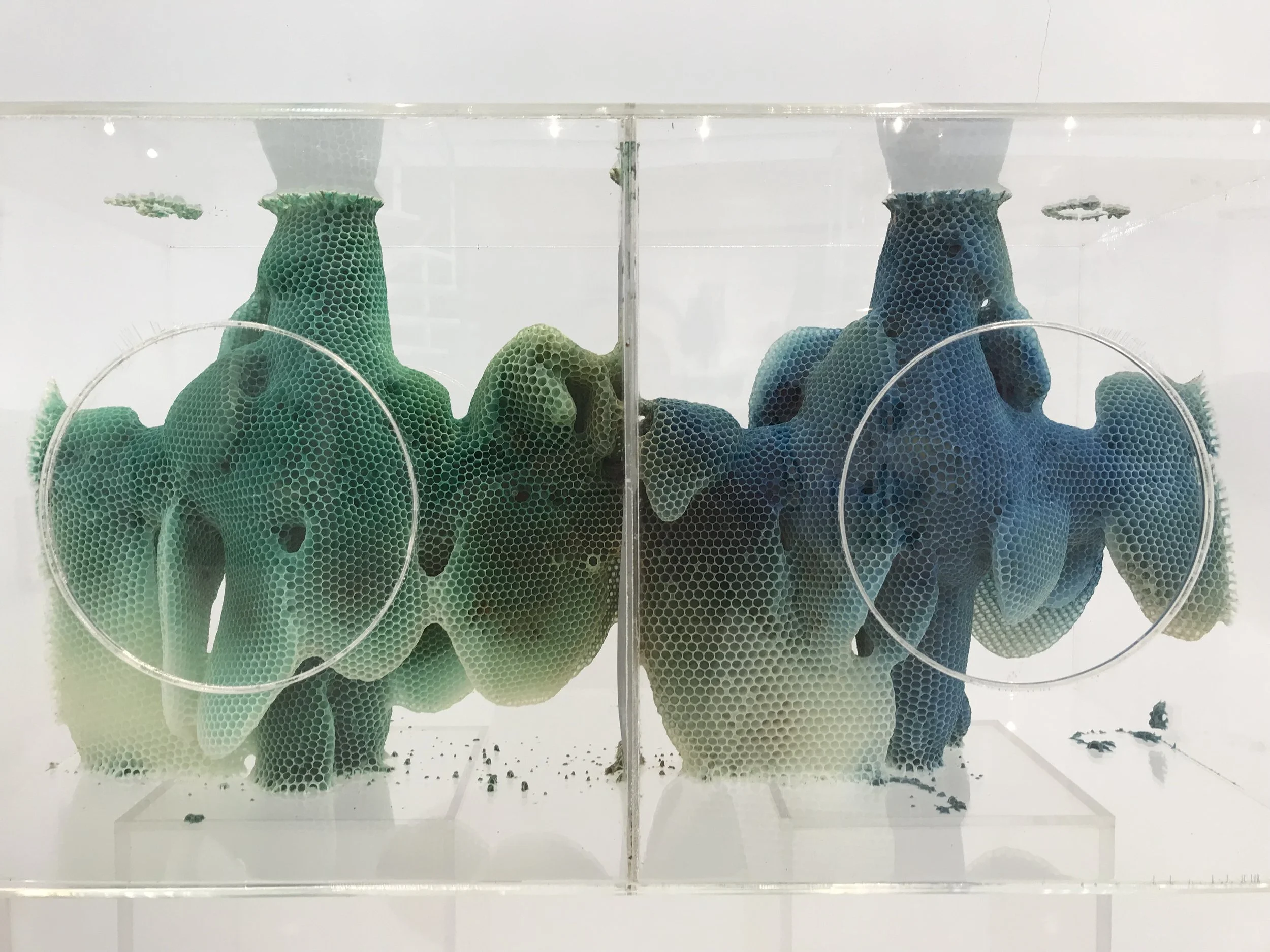

The forces of nature meet the consequences of human intervention in the work of Beijing artist and bee keeper Ren Ri. He has worked closely with bees since 2007: for his Yuansu Chain Series, he supplied them with pigmented water, and rotated their wax constructions regularly to form sculptures which meld nature and artifice in what might be seen as a godlike manner. Ri comments that ‘the bees have their own natural time, which is different from human time’s algorithm. My involvement represents man-made time. My work is the final fruit of the integration of the two different times, which needed to be harmonized’ (xiii).

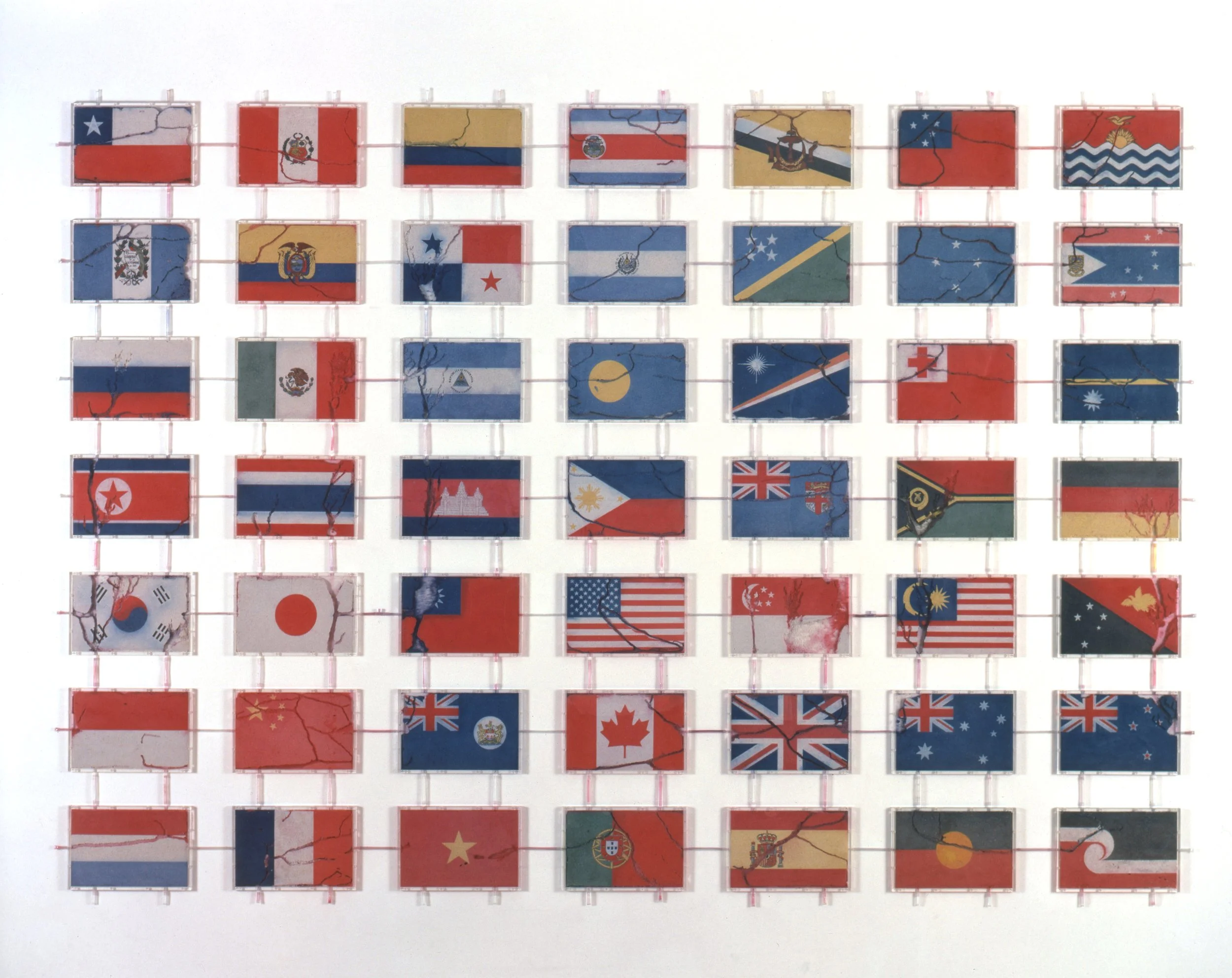

Yukinori Yanagi mounts entire ant colonies in transparent displays of colourful sand arrangements, here forming 49 national flags – representing recognised nations, former colonial powers and indigenous peoples of the Pacific Rim. That mixture acknowledges the contestation of territorial authority and national identities that characterises the region’s history. The ants displace the sand grains, creating tunnels in the sand that read as breaking down the political boundaries: initially as a performative display, and subsequently as the fixed results. One might read into that the chance factors which have brought about many such boundaries, the present fact that such borders have no authority over the natural world, and the future certainty that insects and what they do will outlast humanity and its nations. Yanagi himself has suggested that when the ants erode the clear boundaries between the flags, this serves as ‘a simple, equal and hopeful way of expressing the gradual unification of all the world’s nations’. And it’s appropriate that the demonstration falls to ants: they are one of those complexly social species in which collective action enables vastly more success than would be available separately to the individuals involved. Humanity could learn from them, it being so easy to find examples of how national human collectivity, by way of contrast, can magnify our faults.

Steve Kutcher, also featured in our 03: Entomology Edition, might be placed in the tradition of Maria Sibylla Merian, being an entomologist who makes art as much as artist with an interest in insects. He established a career as a ‘bug wrangler’, persuading insects to ‘act’ for commercials, TV shows and feature films. In the 1980’s he was working on a project with Steven Spielberg, and as Kutcher explains ‘they asked me to have a fly walk through ink and leave fly footprints’. That led him to continue using insects as living paintbrushes. He applies water-based paint to the ends of their legs, and puts them on wet paper so you can see the footprints. ‘I find it fascinating to watch insects walk’, he says, ‘they can walk across ceilings and glass and sand and water, and I noticed different patterns. Sometimes they would drag their feet, sometimes hop, skip and jump. Now you normally wouldn't notice this, but by putting pigment on their feet it opens up a whole new world of walking.’ And if he shifts or turns the paper, that can cause the insects to create different angles, curves or circles. He works with various insects, as if they are different brushes; and such variables as the temperature, the time of day and the lighting conditions are also influential. As for Eleven Steps, Kutcher notes that ‘the hissing cockroach is a very strong insect with the advantage that it drags its abdomen’, so in addition to the feet he ‘can put multiple colours on the abdomen on the underneath side, and as it walks along it mixes the colours.’

By ‘using a combination of insects and a combination of techniques’, says Kutcher, ‘the number of possibilities is endless’. And that provides him – like Finch, Neuenschwander, Ren Ri and Yanagi — with something that many artists seek: a method that they can only partly control, so that chance factors play a significant role, keeping the language fresh. Compare currently, for example, Ian Davenport’s use of poured and thrown paint, or — more elaborately — Niki de Saint Phalle shooting at bags of paint attached to the canvas, or Alberto Burri applying a blowtorch to plastic.

Overall — whether starring in, becoming, or even making it — insects have a more significant role in art than one might have expected. And that makes some sense: not only does it often introduce topics of interest, it is consistent with more notice being taken of the most populous life on earth, and with recognising that insects matter to all the other life forms with whom they share the planet.

Footnotes:

i. See Marcel Dicke’s analysis of ‘Insects in Western Art’, American Entomologist, Winter 2000.

ii. The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí, 1942.

iii. See for example Debbie Hadley: ‘Praying Mantis Mating and Cannibalism’, 2019.

iv. From Sarah Gillespie’s blog.

v. Taylor Lauster: ‘Butterfly and Moth Scales’, The Particle Analyst, c. 2005.

vi. Thomas Eisner in For Love of Insects, Bellkapp Press, 2003.

vii. As quoted by Ian Sample in ‘Why are moths attracted to lights?’, The Guardian, 2024.

viii. Samuel T. Fabian et al: ‘Why flying insects gather at artificial light’, nature communications, 2024.

ix. In her contribution to the monograph Heather Phillipson, Prestel 2020.

x. ‘Are fruit flies radiation resistant?’, Dr Killigan’s blog, 2023.

xi. Paris Project conversation with Jan Fabre, 2015.

xii. Interview with Ben Luke in Art World, April/May 2009, pp.96–9.

xiii. Interview with CLOT magazine, 2017.

All images shown courtesy the artist, gallery, and photographer ©️ All rights reserved.