DOUG AND MIKE STARN: SCIENTIFIC ANALOGIES

The Starn Brothers are effectively one artist – Doug and Mike are identical twins, born in 1961, who work on everything together in a vast studio in Beacon, New York – and finish each other's sentences in the way one might expect. HackelBury Fine Art in London currently has an excellent overview of their practice, combining new work with judicious selections from six of their many previous projects across a forty-year career.

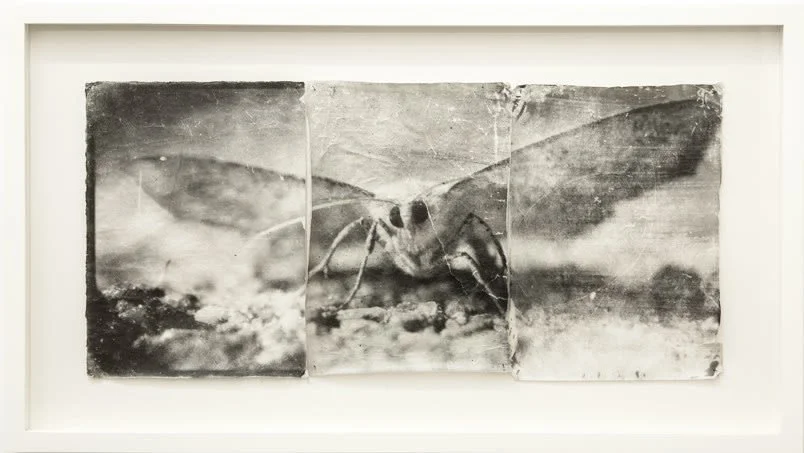

The Starns started from their interest in nature and art, together with a scientific mind-set – they like to take things apart then put them together again. Beauty unquestionably results, but the real point of their work lies in the analogies their processes yield. Early on they ‘started to get obsessed by light, and what was in it metaphorically for us’ (1). That led to ‘Attracted to Light’: a project photographing moths, which they thought of as ‘little creatures coming out of nowhere and flying towards the light’ (2).

The scales that cover moth wings are complex and fragile structures that snap into individual pocket-like slots to stay attached, helping them to find friction in the air. After touching a moth’s wing a layer of what appears to be dust will more often than not be left on a person’s hand. As the Starns say, ‘their wings are really dusty from scales, and so we aimed to reflect that by using a silverprint process that led the images to fall apart in the development’. The prints are on Mulberry tissue paper, stronger than it looks when scuffed, abraded, and torn, operating rather like moths that can get very tattered and yet still fly.

Moreover, the prints range from three inches to twenty feet wide, enabling the viewer not to just examine the moth, but to think of them on their scale, to see themselves as moths searching for the light. Doug and Mike also found that moths ‘actually have a different sense perception than we do – we have a complicated sense of vision and process what we see 30 times a second; moths just see light and dark but see things 10 times faster than us. They see more within each moment – one second for a moth takes ten of our seconds, their mind goes into a hyperdrive. That was a revelation about how perception really is individual, we’re all making the world inside our minds’.

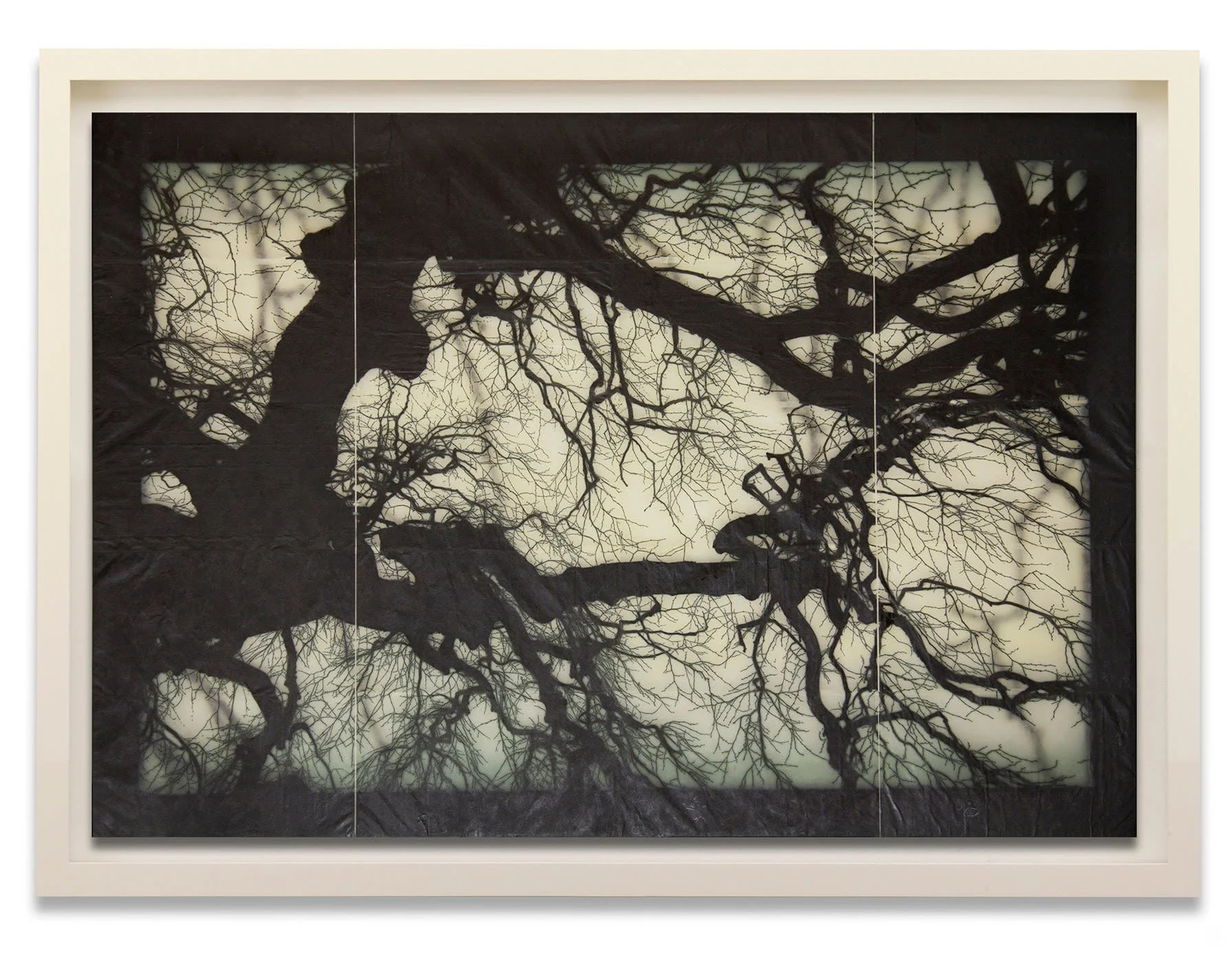

Trees, of course, also seek the light, creating patterns of natural architecture and shadow. What led the Starns to the series ‘Structure of Thought’ was that, although a tree is a hierarchical system of trunk, branches, and twigs, ‘when you silhouette it, the whole hierarchy is collapsed, and connections happen everywhere’. That reminded them of how you can take a thought anywhere, you do not have to go in any particular direction. Moreover, the silhouetted images have something of the brain’s system about them: trees and brains are similar branching structures, and both use a central trunk to send signals to a network, with the nervous system's central trunk being the brain and spinal cord, and its branches the peripheral nerves (3). The Starns subtly emphasise this in their large prints by using layers of wax, with trees in front of a back layer that does indeed show microscopic views of the neural paths in the brain.

Drilling down from trees to leaves, the ‘Black Pulse’ series is again about light – and also darkness. The Starns scanned leaves – they didn’t use a camera – then ‘in Photoshop we were able to separate the skin and flay the leaf to just show the veins where the carbon is being inhaled into the tree and absorbed into creating it’. The life of leaves – the lungs of the tree – relies on photosynthesis, the process whereby the chemical chlorophyll assists in turning water and carbon dioxide into sugars as energy for growth. For the Starns, the process is a fitting trope for photography itself, for both rely on light to develop latent forms and bring them into being.

The leaves of ‘Black Pulse’ are wrought in remarkable detail, bringing out their sculptural beauty. And there is also a deep connection to the human, as the carbon revealed as inhaled through the leaf is the same carbon we exhale. That is likely to put us in mind of the 50% increase in carbon dioxide since pre-industrial times that has led to global warming (4). Not only does one large tree provide a day’s supply of oxygen for as many as four people, but it will also absorb more carbon dioxide than a person exhales. That illustrates the beneficial effect of the tree – though, of course, the warming is not down to our breathing: that is part of a balanced natural cycle. As the carbon comes from the food we eat, which was originally captured by plants through photosynthesis, it does not contribute to the net increase of atmospheric CO₂ – unlike the CO₂ from burning fossil fuels, which a tree's absorption can help offset. That leaves say so much about life and death is reflected in the Starns’ presentation: half are printed on glossy paper, emphasising life; half on visibly fragile paper, emphasising death.

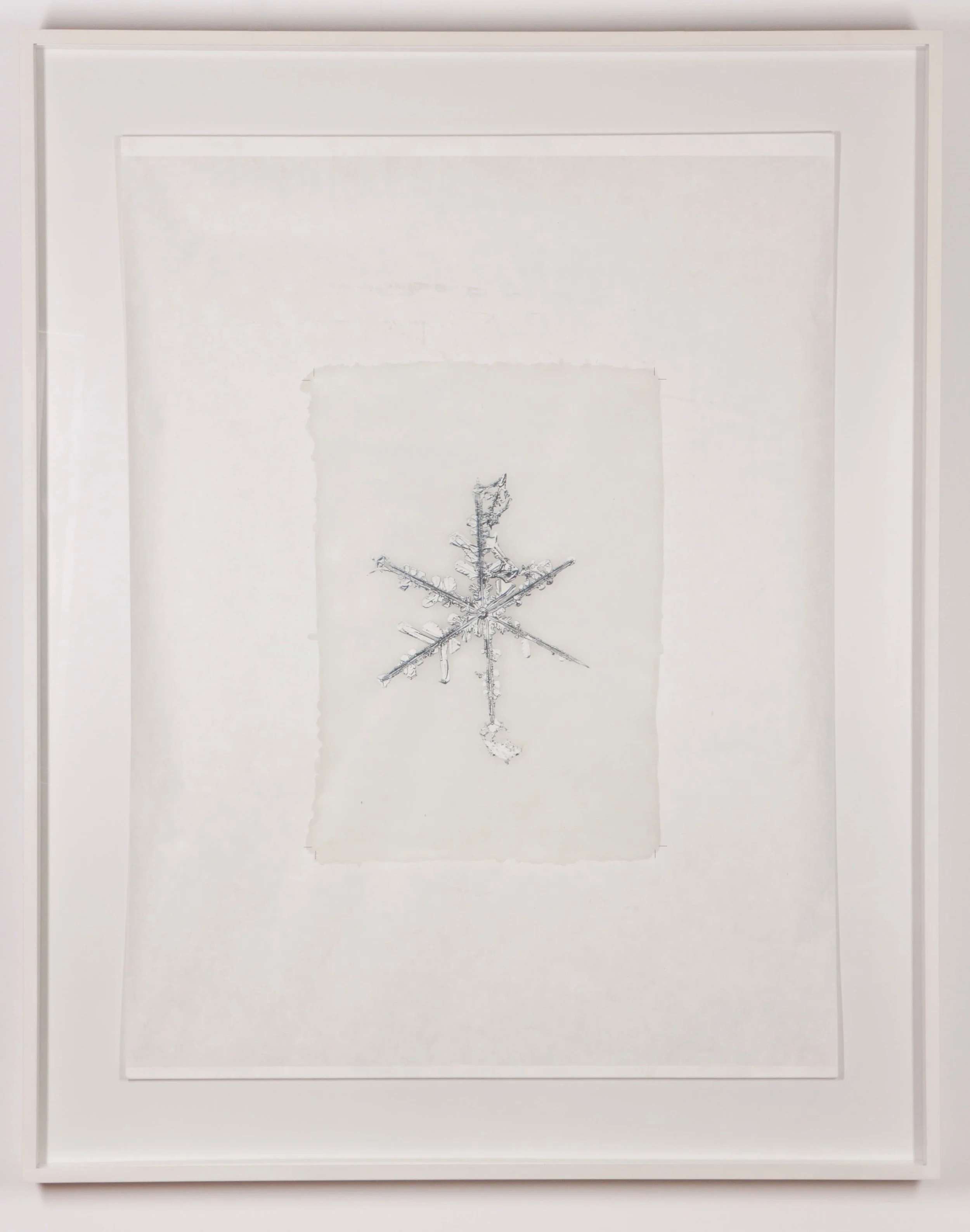

Visually, those leaves share something with the 2005 series of snowflakes, ‘alleverythingthatisyou’. That uses photography and mixed media to capture the structural complexity of snowflakes, connecting them to broader themes of chaos, order, and interconnectedness. Technically, it was complex: the Starns spent five years developing a set-up capable of doing what was needed. For example, when the snow landed it needed to be lit, but that would melt the flakes, so engineers were called in to develop fibre-optical lighting. The brothers were happy to shoot whatever snowflakes came, they did not have to be perfect – as few are, after the tribulations of their formative journey.

The ice crystals that make up snowflakes are symmetrically patterned because they reflect the internal order of the crystal’s water molecules as they arrange themselves in predetermined spaces to form a six-sided snowflake. It is the temperature at which a crystal forms – and to a lesser extent the humidity of the air – that determines the basic shape of the ice crystal. Thus, we see long needle-like crystals at -5°C and very flat plate-like crystals at -15°C. The intricate shape of a single arm of the snowflake is determined by the atmospheric conditions experienced by the ice crystal as it falls. And because individual snowflakes all follow slightly different paths from the sky to the ground – and, consequently, encounter slightly different atmospheric conditions along the way – they famously appear unique, resembling everything from prisms and needles to the familiar lacy pattern (5).

The snowflake project started from Doug and Mike’s interest in minute things making up larger things … Just as an igloo is made up of snow, so the snow itself, they say, ‘is like an igloo, made up of all these tiny moments – planned / unplanned, chaotic / resolved, fragile / strong – all at once’. There turns out to be an analogy between how our personalities and mental worlds are formed, and how snowflakes come about.

That analogy is pushed further in the ‘Big Bambú’ series of large-scale, immersive, and evolving installations built from thousands of bamboo poles lashed together with nylon rope, forming expansive, organic structures that resemble a living, growing organism. These installations often invite audience participation, allowing visitors to walk through, climb, and interact with the sculpture, further emphasising the idea of constant change and evolution. That they use bamboo is not the point, the Starns stress, they simply came across it as the perfect bearer to represent the interconnected elements that create the structure of life. Not unlike the snowflakes, that relates to ‘our own personal philosophy of how things grow – whether that be culture, person or family – from random occurrences, trajectories from history or politics or fears or hopes … All these things interconnect, and we travel forward through these interactions, regardless of our plans. That is how we move forward in life. We thought this would be physically demonstrable as a sculpture that played out over time, always complete but never finished’. The initial version ran to 7,000 poles and over 100 miles of rock-climbing cord as they continued to build it over the six-month run of an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, in 2010. The image is of the fourth iteration in Jerusalem.

The most substantial part of the Starns’ current London show, ‘A Tragedy of Infinite Beauty’, presents two new bodies of work, ‘Under the Sky’ and ‘Everything Is Liquid’.

‘Under the Sky’ features clouds, bringing what is normally in the background into prominence in photographs made to look more painterly by overlays of acrylic paint, varnish, and wax. That fixes what is, perhaps, the ultimate symbol of ephemerality. As the Starns put it: ‘The cloud is the inevitable thought, the thing with no permanent shape, drifting through the clarity of blue and silent mind. As the cloud changes continually, the watcher only watches it until losing interest, and as awareness of it slips by, the thought’s gone out of sight. They always will be – old, worn, and always new.’

The setting for the clouds is, of course, nothing but an ocular phenomenon, the perception of light in the atmosphere. By day, that tends to appear blue to us, due to Rayleigh scattering (6), named after the British physicist Lord Rayleigh (1842-1919). He established that when light is scattered by small molecules in the atmosphere, the percentage of light scattered is inversely proportional to the fourth power of the wavelength. Red light has the longest wavelengths (620-750 nm) and violet has the shortest (380-450 nm), meaning that when violet light encounters a particle at least one-tenth the size of its wavelength, it will scatter far more efficiently than red light would. So, when light from the Sun encounters atmospheric nitrogen and oxygen molecules, they scatter more of the violet and blue light waves. That diffuses them throughout the atmosphere and makes the sky appear blue (rather than violet, because the human eye is more sensitive to blue light waves).

Red, orange, and yellow light waves are more likely to pass through the atmosphere without scattering. As a result, the midday Sun appears yellow, because more of those light waves are able to reach the human eye. As the Sun nears the horizon at sunset and sunrise, its light must traverse considerably more of Earth's atmosphere than during the day. The violet and blue wavelengths have to pass through up to forty times more air molecules to reach us, allowing these wavelengths to be absorbed and redirected multiple times, scattering away in all directions. Then the red and orange wavelengths that are left over make their way through the atmosphere, giving the Sun and the surrounding sky a red and orange glow.

Whatever its apparent colour, you cannot touch the sky. Yet the Starns, paradoxically, make it into ‘an object to touch … stained paper, taped and glued together … made by hand – see the grit’ and ‘pasted crudely,’ so that they will not lie flat. That sculptural presentation recognises how the sky is real for us, in line with which they find a striking analogy for the untouchable nature of the sky: ‘the beauty of life is true and real even though you can’t touch it.’

The eponymous ‘tragedy’ in this ‘infinite beauty’ is the sublime indifference – by day or night – of the sky above us. That has a long history as a poetic trope. W.H. Auden (7) can stand in for many:

‘Looking up at the stars, I know quite well

That, for all they care, I can go to hell,’

In the Starns’ words: ‘The Sky covers and continues at all times and in all places, covering us, over us. With its beauty, the horror we create on each other is made all the more horrific. It is a tragedy of infinite beauty with no regard of our never-ending war waging and the oppression of each other. The Sky is completely, and utterly, oblivious.’ Auden concluded similarly:

‘But on earth indifference is the least

We have to dread from man or beast.’

Yet there is hope, say the Starns, as ‘the beauty of the sky both shames and inspires. The situation is our own making, and the sky is ours ... taking cover under its beauty, it is beauty to strive for, try to live up to it, to see our reflection in it, recognise it.’ Consistent with that, the titles of the series – ranging from ‘it’s love and sympathy’ to ‘people searching a building after an airstrike’ cover a wide range of emotional scenarios as they play on our anthropomorphic tendency to read things into clouds.

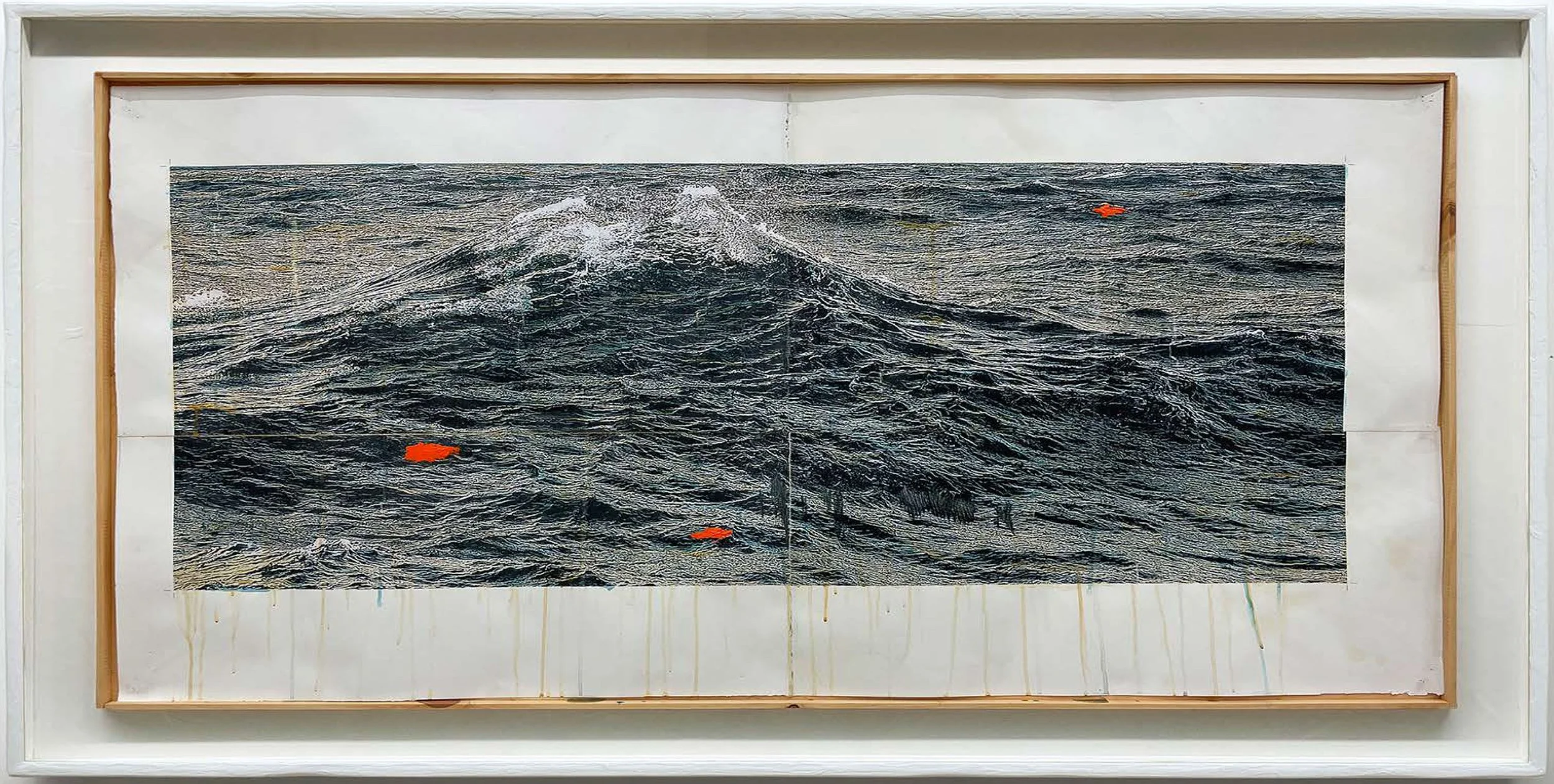

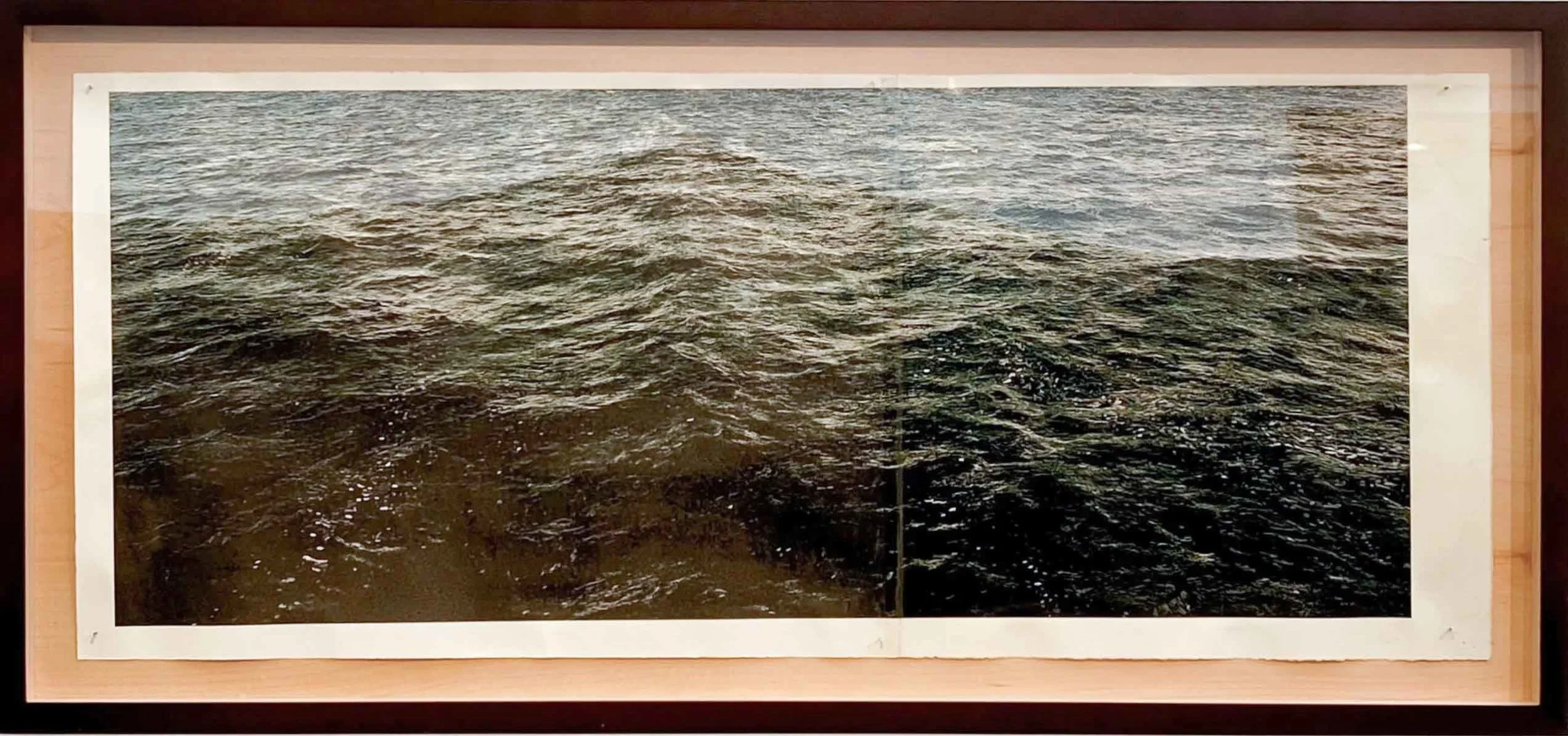

The thematically interchangeable mountainous and watery landscapes of Everything is Liquid also explore transformation, the idea that everything is fluid and constantly changing. For the Starns, explain HackelBury, ‘vision is not a passive act, rather an active process, taped together moment by moment, formed and reformed as we move through the world. As with the landscapes they depict, we too are fluid, evolving, incomplete’.

What we see, then, is the geological time of mountain movement contrasted with the sea’s speed – all under the meteorological time foregrounded by ‘Under the Sky’. Up close, the images disintegrate into an outcome some distance from straight photography. Doug and Mike describe themselves as ‘taking the visual clarity of the high-definition digital photographs, zooming into the details of the image until they begin to fall apart’, and so ‘destroying the photographic detail and three-dimensional illusion while retaining elements of the scene. We explore the noise and then digitally smooth and discover an interesting pattern within it, we strip out tonality and find something that looks like a woodcut’. The images are then brushed with water and overpainted while vertical so that trails of paint form rivulets. Finally, orange highlights are added to suggest reflected sunlight while increasing the compositional energy. The results channel something of the Japanese way of celebrating imperfection. That carries onto the framing – the Starns hand-make them to set the images at varying depths, and to ensure a slightly ‘imperfect’ finish that is obviously hand-made. The result is ‘paintings that are photographs that look like woodcuts and that are painted, in frames, within sculptures of frames. What is real? And further in that direction – what art is real, and what art isn’t? The questions are slippery; they don’t stay still.’

Doug and Mike explain that they are using ‘the obvious comparison of the constant rising and falling choppy water with the geologic change of the earth caused by turbulence and collision. Since the beginning, an ongoing part of our work has been Seascapes – always changing but always the same, a body of water in constant motion, crashing against itself, captured in a fraction of a second by the camera. In this series the seascapes are in comparison and contrast to the Mountain-scapes; the indescribably slow-motion tectonic plates colliding and creating similar dynamic and dramatic forms. Seemingly permanent and eternal, our human timeframe not even a blip in geological time, the mountains are a living photograph that we witness in progress over our lifetime with our eyes. Mountains appear static, but nonetheless the landscapes are changing all the time’.

Just how fast do mountains move? The primary driver of their formation is the slow collision of tectonic plates, which move at up to 4 cm per year. That causes the land to buckle and push upwards. The Himalayas, for example, which have taken 50 million years to reach their current height, are rising by around a centimetre annually. That plate movement can also cause drift: the Alps, moving much more slowly than the Himalayas, show a combination of drift (0.2 mm per year) and rise (0.5 mm per year). Recent research has also shown that mountains, like tall buildings, vibrate at predictable resonances on the basis of their topographic shape (8). The Matterhorn, for example, is in constant motion, gently swaying back and forth at a frequency of 0.42 hertz, or slightly less than once every 2 seconds, because of the ambient seismic energy originating from earthquakes and ocean waves around the world.

What is interesting in the context of ‘Everything is Liquid’ is that this phenomenon demonstrates a real-world connection between mountains and oceans. Ocean waves moving across seafloors create a continuous background of seismic oscillations, known as a microseism (9), which can be measured around the world. And that microseism has a frequency similar to the resonance of the Matterhorn. The excitation of the mountain is largely down to the sea.

Doug and Mike Starn: A Tragedy of Infinite Beauty runs 9 Oct 2025 – 28 Feb 2026 at HackelBury Fine Art, London.

Endnotes:

Quotes from Doug and Mike Starn are from their conversation with Gary Tinterow at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston in 2022, and from their correspondence with HackelBury Fine Art in preparation for the show ‘A Tragedy of Infinite Beauty’.

In fact, recent research shows that moths are not attracted by light so much as trapped by any light they happen to fly past: we’re less likely to notice the many moths on routes further from the light. Moths do not steer directly toward the light. Instead, they turn their dorsum toward the light, generating flight bouts perpendicular to the source. Under natural sky light, tilting the dorsum towards the brightest visual hemisphere helps maintain proper flight attitude and control – an evolutionary advantage. Near artificial sources, however, this response can produce continuous steering around the light and trap a moth.

Michael Netzley takes this metaphor further in ‘Your Brain is Like a Rain Forest’ in Medium, 2022.

See, for example, Owen Mulhern: ‘A Graphical History of Atmospheric CO2 Levels Over Time’ at Earth.Org, 2025.

How Snowflakes Form National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, USA, 2022.

See, for example, Richard Sheposh: ‘Rayleigh Scattering’ at EBSCO, 2024.

From W.H. Auden: ‘The More Loving One’, 1957.

Richard J. Sima: ‘Mountains Sway to the Seismic Song of Earth’, EOS 2022.

‘Microseisms are continuous seismic disturbances of the earth's surface that constitute the normal background oscillations of seismograms… The most prominent microseism signals are related to marine storms’ - William L. Donn: ‘Microseisms’ in Earth-Science Reviews, 1966.

All images shown courtesy the artists and HackelBury Fine Art, London ©️ Starn Studios.