03 TBA21–ACADEMY: TALOI HAVINI

PACIFIC STATE OF MIND

‘I don’t come from the earth’, says interdisciplinary artist Taloi Havini, ‘I come from the ocean’. Though now based in Sydney, she was born into the Hakö community on the small Pacific island of Buka, and the essence of her art is to communicate the difference that makes. Indeed, she describes herself as ‘an islander first and an artist second’. Buka is a 500 sq km island of coral and limestone, sitting on tectonic plates some 3,000 miles north of Australia. It’s the smaller of the two main islands – the other is Bougainville Island – which make up the Autonomous Region of Bougainville, population 300,000. The islands, formerly part of the North Solomons, are incorporated into Papua New Guinea.

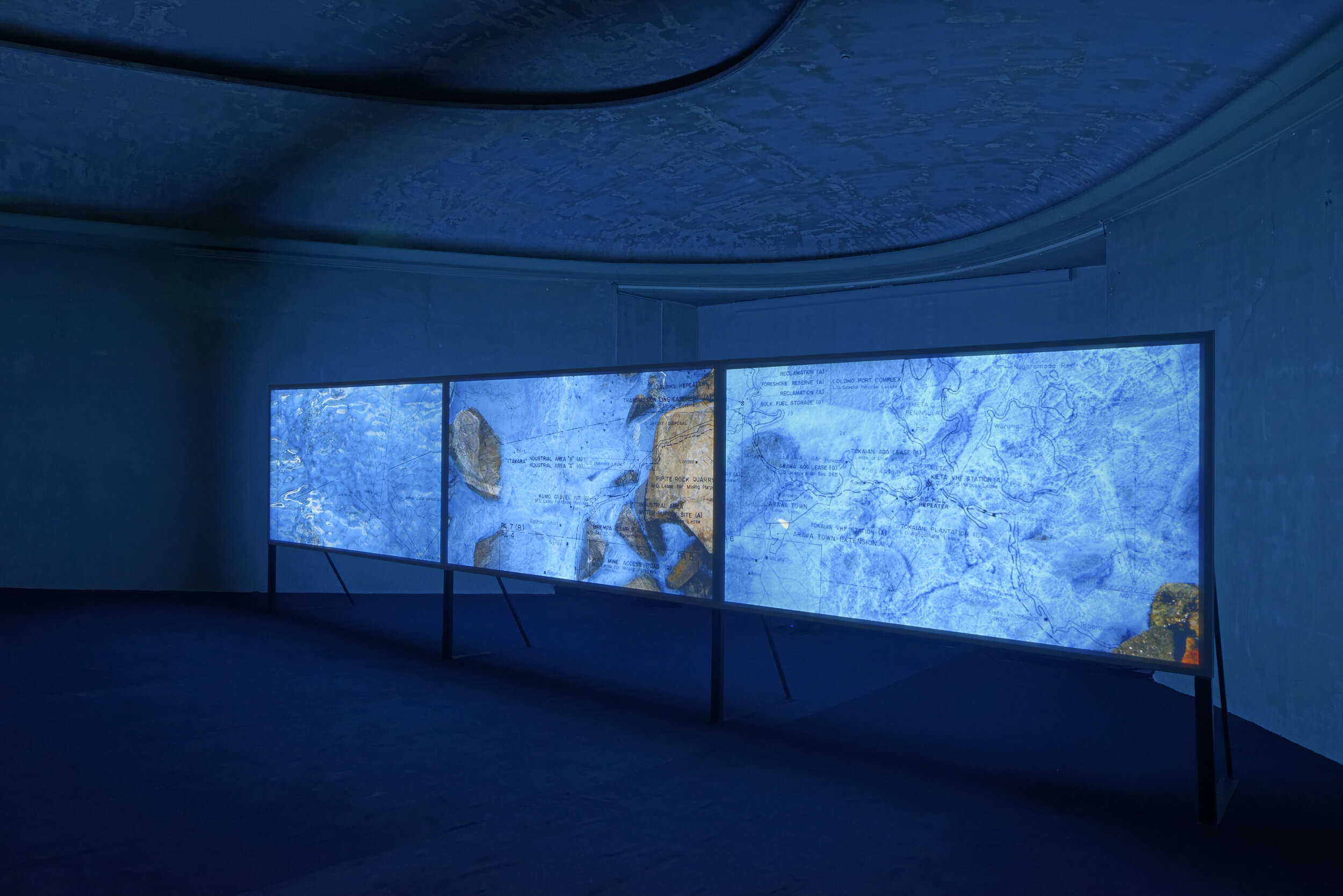

Havini’s work has typically explored contested objects and sites. Reclamation (2020) was an extensive installation made collaboratively with her Hakö clan members for an exhibition in Sydney: a sand-filled room with seven dramatically spot-lit cane and vine structures resembling archways decorated with traditional patterns. The resulting shadow play accentuates them as presences rather than simple objects. Or, as Havini puts it: ‘underlying the ephemeral installation of cane and earth, are questions about the ways in which we relate within temporal spaces; how borders are defined and claimed as well as the value of impermanence and embodied knowledge over fixed historical understandings.’ The Habitat series (2018-19) is a more complex installation with four video screens. The subject is the Panguna mine, which was the world’s largest open-pit copper and gold working from 1972-89. Havini describes it as showing ‘the extractive industry in Bougainville and how it changed coastal systems’.

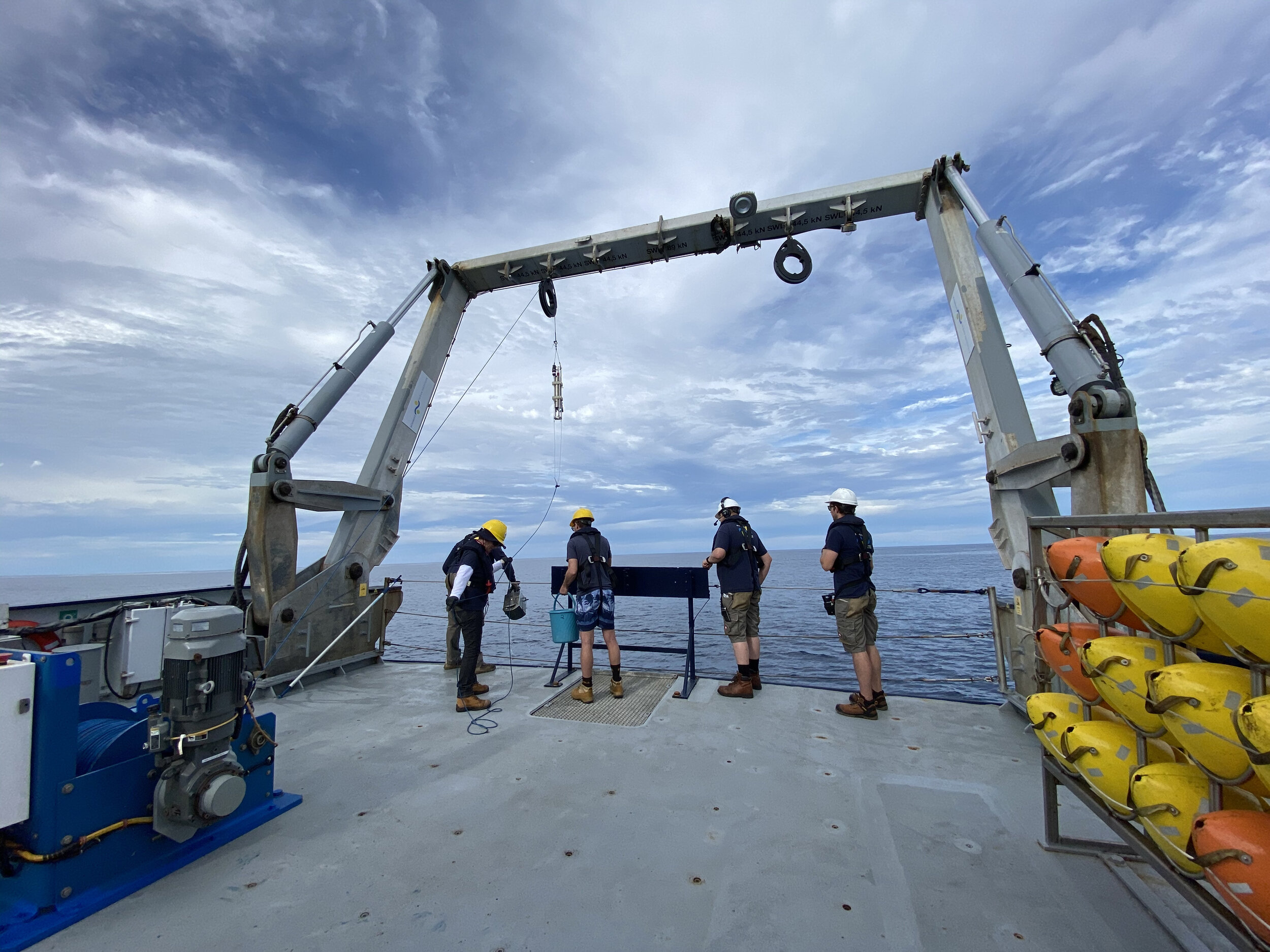

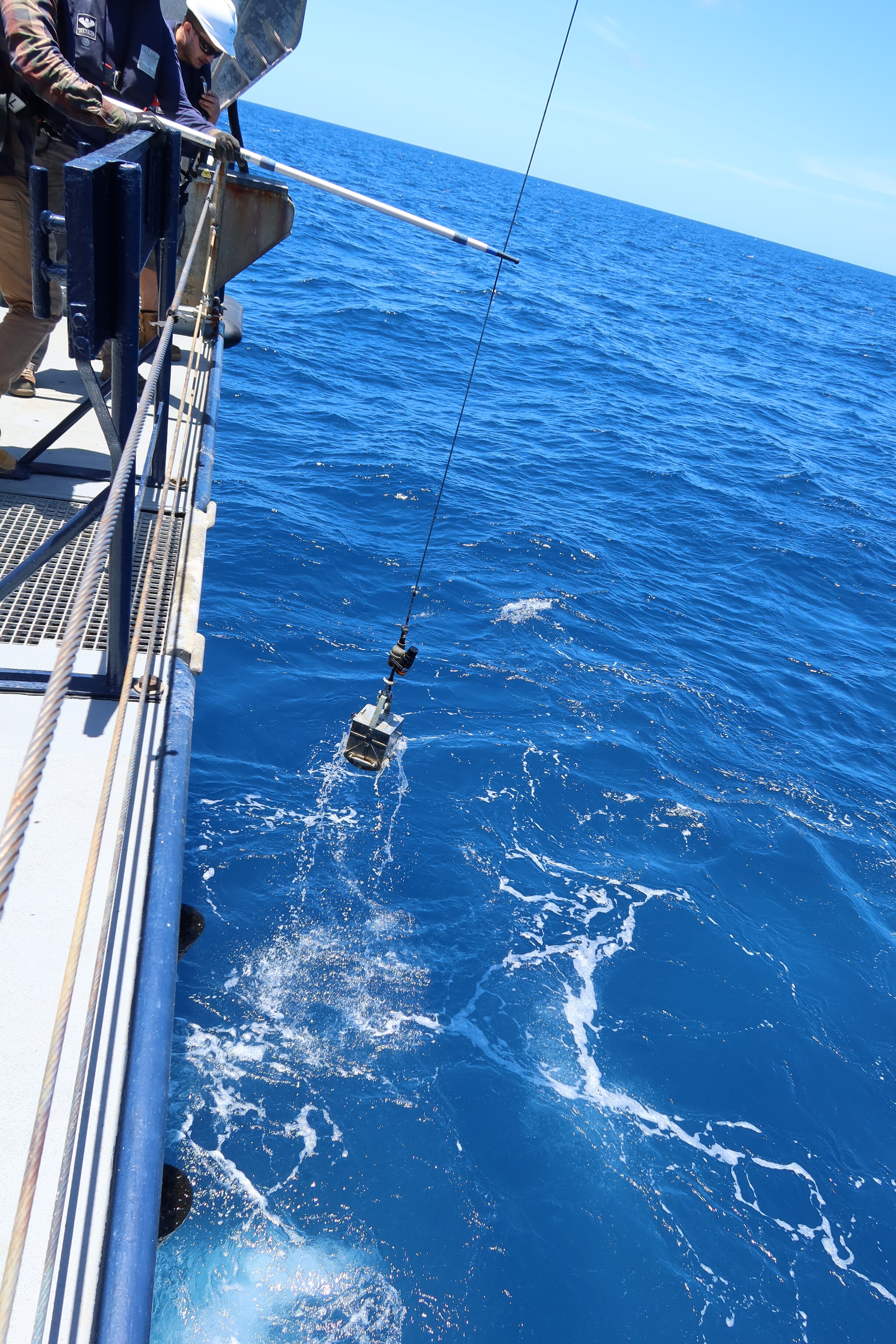

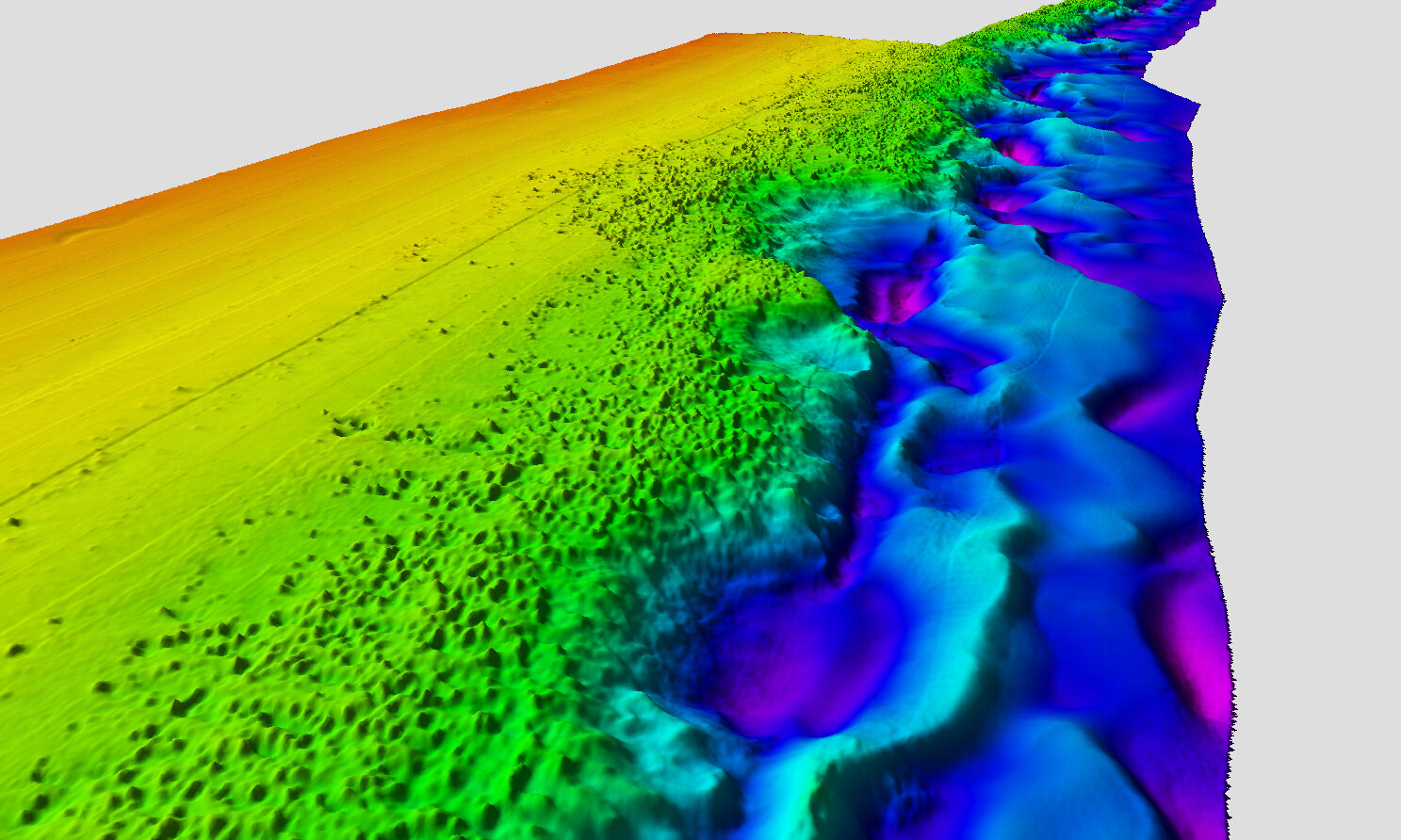

In December 2020, Havini spent three weeks on the scientific research vessel R/V Falkor. Taking part in Schmidt Ocean Institute's Artist-at-sea program to support the research process for her upcoming commission for TBA21–Academy for its exhibition programme ‘The Soul Expanding Ocean’, she was to observe the Institute’s bathymetric methods of mapping the Australian Great Barrier Reef sea-bed (TBA21, 2021). The ship travels at a steady 8 knots, while echo sounders push out acoustic pings down to the sea floor, using the time interval between emission and return of a pulse to determine the depth of water. That feeds into a computer system which enables the bottom of the ocean to be visualised in high resolution detail. The colour-keyed maps produced, as Havini says, ‘make it look like it could be land – and it once was – the sea level was 120m lower in the Ice Age period than it is today (see: Farrell and Clark, 1976). Pacific Islanders, says Havini, are comfortable with technology, but have no particular need to draw maps in that way ‘as we know the land – and we use sound as part of knowing a place’ – as the spoken words of storytelling and oral histories are how information is transmitted through time. ‘Our idea of space and time isn’t about looking at the surface and drawing it, and having an artefact with lots of data sets and layers. Our idea of mapping is about storytelling and observation of the world around.’ She wonders whether ‘the visual emphasis of mapping means we’re missing out on other stories – on personal ways of connecting to place’.

Stemming from that trip and those thoughts, Havini’s new work will run until mid-October at Ocean Space, Venice – which was, until 2019, the spacious 17th century Church of San Lorenzo. The term ‘immersive installation’ could have been invented for Answer to the Call (2021) – which might be seen as an alternative mapping of Buka. Visitors walk around and through a land-and-seascape in three shades of blue – indigo, ultramarine and aquamarine – representing the various depths of water in the reef system. They can climb a few steps to stand on a floor-based shape, which takes the form of Buka island; or walk around cloth-covered scaffolds which suggests underwater mountains or the sea towering above. This acts as the stage set for 22 speakers at three levels, transmitting 22 different 40 minute cycles of sound. The tracks are a mixture of natural sounds, ancestral Hakö ocean travel chants and music for Hakö instruments composed by renowned Bougainville musician Ben Hakalitz. So, for example, we hear water, hydrophone recordings of sonar mapping, whale songs and birds of paradise. ‘Relate this to when I'm in my village’, explains Havini, ‘or I'm in the ocean – the Pacific Ocean – I'm surrounded by the sky, the night sky, the coral reef. Where I live is a coral reef. We have cliff edges that go straight into the ocean, we live right at the fringes of the coral reef that meets the deep ocean’. Talking of the chants, Havini says they give her goosebumps ‘because these are elders I had recorded about twenty years ago, and all of those people are now not here. These are the chants that they used to sing as we went out onto the ocean, to commute to other islands and to come back. And so that's in there, in part of the sound design. You'll hear it and they sound like old men, and so now they are ancestors. Those chants are about being one with the current, moving with that current; knowing that time, being celestial navigators. They didn't need technology or science, they just went with feeling.'

On the one hand, the set-up evokes the scientific procedure of bathymetry. On the other, in curator Chus Martínez’s words, ‘Havini subverts the gaze associated with scientific exploration, and instead invites the listener to congregate on the island immersed in the shifting tides of sound … The audience – who may never go to the Pacific – are placed in the centre of the conversation Havini is creating.’ They become actors engaged in the pursuit of knowledge as Havini ‘moves beyond a sonic measurement of space and distance to assert the presence of a deeper, cyclical understanding of the ocean, space, and time.’

What does Havini seek to transmit through Answer to the Call? She’s expressing the Pacific world view in order to provide an opportunity for others to understand how it is different, how an alternative form of intelligence might operate. In her words, ‘as indigenous people we look after the land – we’re the traditional owners but really the land owns us. My science is listening to our elders – that’s my indigenous knowledge.’ How does that sit with mapping? ‘The map is a physical presence of time’, she says, ‘here ‘time relates to what it can do for your generation building on what is passed to you.’ That doesn’t contradict the scientific processes of bathymetry (see: Olsen, 2016) and hypsometry (see: Rafferty, 2021) through which an objective measurement of bimodal elevations is mapped. Rather, it offers an alternative way to understand the world, just as the description of mental processes doesn’t contradict, but operates quite differently from, the analysis of neurological data.

The location is, of course, a central part of Havini’s installation. She is bringing her audio-sculptural experience of the ocean to a lagoon with its own unique history, to the culturally richest interaction with water in the western world. And she is doing so in an old and spacious church, a building in which sound has always been important in disseminating messages. Havini’s purpose may be to generate empathy, not reinforce religious belief, but Answer to the Call does have a spiritual intensity.

So how will her audience respond? I can imagine the Ocean Space – which has free entry – becoming a place to chill out, with people lying in the soundscape for the full 40 minute cycle, letting Havini’s Pacific frame of mind flow into their own thoughts. That’s what Havini wants: ‘when you walk into the space’, she says, ‘you will feel as though you are in the Pacific Ocean; you will feel as though you are on the east coast of the Great Barrier Reef; then you will feel that you are in Bolivia; then you will feel as though you're in the Atlantic; as though you're in the depths of the Ocean – you will go down to the twilight zone’. The impact will, moreover, be developed over the course of the exhibition (to 17 October 2021), by various live events and conversations which will be streamed online, refreshing and expanding the experience. Such an alternative space of being might take on some of the hypnotic qualities of the artificial sun in Olafur Eliasson’s The Weather Project at Tate Modern in 2003. Answer to the Call is set to act as a social setting for inner exploration and reflection as visitors join Havini in her project of deep listening.

References

Farrell, W.E. and Clark, J.A., (1976). On postglacial sea level. Geophysical Journal International, 46(3), pp.647-667.

Olsen, R.C., (2016). Remote sensing from air and space. Bellingham: Washington.

Rafferty, J.P., (2021) Hypsometry [Online] [Accessed 21.07.21] Available from: https://www.britannica.com/science/hypsometry

TBA21, (2021) TBA21–Academy presents “The Soul Expanding Ocean #1: Taloi Havini” and extends “Territorial Agency: Oceans in Transformation” at Ocean Space, Venice [Online] [Accessed 21.07.21] Available from: http://press.tba21.org/news-tba21academy-presents-the-soul-expanding-ocean-1-taloi-havini-and-extends-territorial-agency-oceans-in-transformation-at-ocean-space-venice?id=121880&menueid=9361&l=english

All images and audio shown courtesy of © 2021 Taloi Havini