04 TBA21–ACADEMY: CLAUDIA COMTE

CONSIDERING CORAL

While one would hope that artworks won’t damage the environment, it’s hard to think of many which positively improve it. That, though, is one of the aims of Claudia Comte’s installation of underwater sculptures off the Jamaican coast, which also provides a positive answer to the question ‘can the ocean be an art space?’ Comte has installed a colony of concrete sculptures, sixteen metres below sea level, specifically designed to provide a hospitable place for coral to grow. If that seems fairly straightforward, there are actually three factors which make it more surprising – paradoxical, even: Comte’s own origins, her typical material, and the forms she has chosen to sculpt.

First, her origins. Far from being born into harmony with the oceans, Comte comes from the wooded alpine region of the Jura Mountains in the French-speaking part of landlocked Switzerland. She grew up in a chalet in Morges, a village of 300 people, and has returned there regularly, both when she was based in Berlin as an emerging artist, and following a recent relocation to the countryside near Basel. So how did she come to the sea? ‘In March 2018’, she explains, ‘I was invited to participate in an oceanic expedition to New Zealand organised by TBA21–Academy, led by the curator Chus Martínez, together with a crew of fellow artists. Since this experience, I have developed several works and artistic interventions that incorporate my oceanic findings.’ The trip also brought home to Comte how ‘most people don’t understand what’s happening underwater. It can seem like one giant mysterious alien world to us’ – one she wants to help people to engage with.

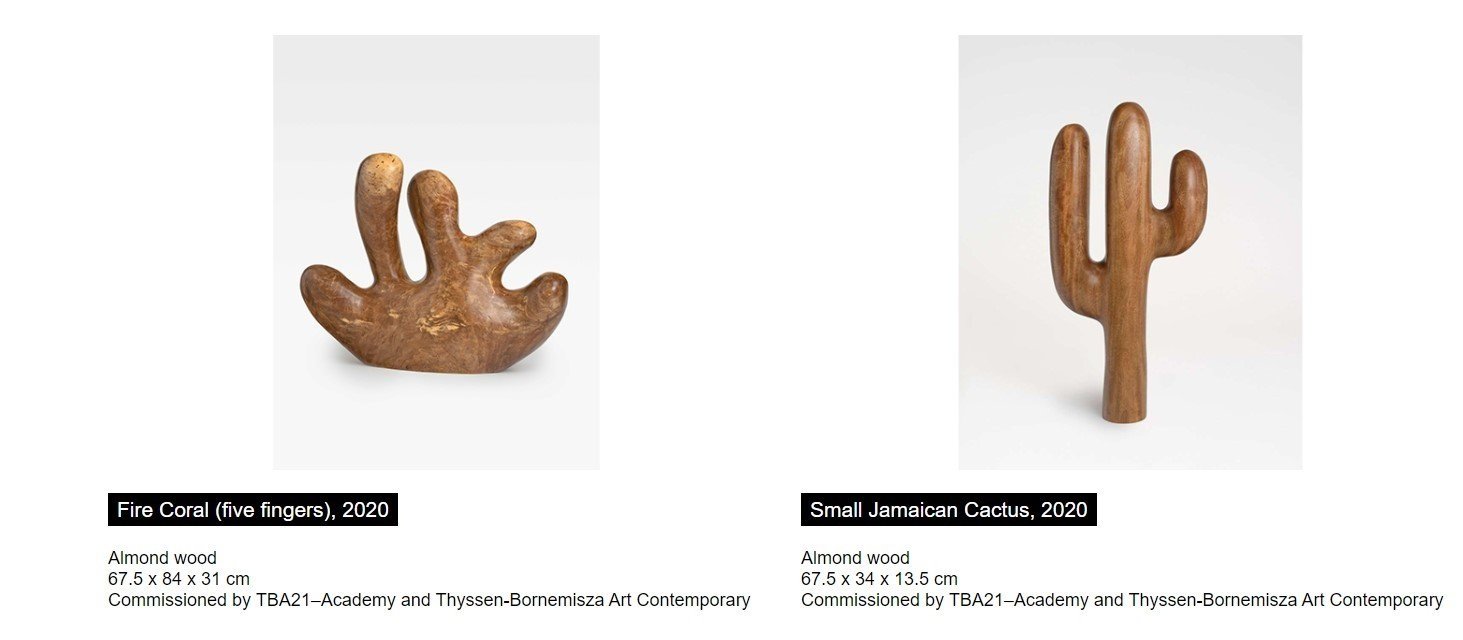

Second, the material story. Comte makes wall paintings, films and installations as well as sculptures, but – consistent with her origins – her signature material is wood. She cuts sustainably sourced trees into semi-abstracted shapes with a chainsaw, then smooths them into a finish closer to what one would expect of marble. Comte has been concerned with ecological issues ever since observing the ecosystem at first hand in the Jura, and has favoured naturally occurring materials as a result. The forms she makes have an anthropomorphic aspect, creating an empathetic connection to the trees in which they originate. ‘That’s why I polish my wooden sculptures like a maniac!’ she says, ‘That way, you can reveal the life inside the wood.’ She works with a lumberjack team, and has sometimes had them wield their chainsaws in gallery spaces to perform sculpture-making live, accompanied by a mixture of forest sounds, classical music and techno. Her works straddle two traditions: the modernism represented sculpturally by Brancusi, and the cartoon: one can imagine Comte’s forms inhabiting the landscapes through which Wile E Coyote chases the Road Runner. Indeed, Comte cites a student trip to California – the source for those cartoon landscapes – as formative. Her work thrives on dichotomies, and that combination of influences sets up contrasts between rural and urban, organic and geometric, funny and serious as well as land and sea, cartoon and modernist.

The underwater sculptures were developed in wood, on site at her residency at Alligator Head Foundation in the East Portland Fish Sanctuary, a conservation area established in 2016 and managed by the foundation and Jamaica’s Ministry of Industry, Commerce, Agriculture, and Fisheries. Spanning six square kilometres, the sanctuary protects an array of critically endangered species including elkhorn and staghorn coral, reef fish, and turtles. Comte’s wooden sculptures were then created in reinforced concrete for installation. Concrete, selected for its capacity to withstand ocean currents, also provides a habitable surface for coral growth, with the aim of promoting coral resuscitation. An experienced scuba diver, Comte was in the water as her works were lowered and knew enough about diving to recognize how impressively the heavy works were manoeuvred into place. ‘As a diver’, she says, ‘you are told to always remain as relaxed as possible and to not exert too much energy, so it was really something to see what can be done, all while underwater and masked.’

The third paradox lies in Comte’s subject. The underwater sculptures are of cacti. That may seem even more unlikely than finding a Swiss forest dweller dedicating herself to the sea, but Comte sees the irony as more than humorous. ‘Cacti represent the arid terrain of the desert’, she explains, ‘and symbolize for me a potential future version of the earth subject to desertification … a time in which, rather than trees, the Earth is covered with cacti. Placing them on the seabed creates quite a rupture, while also conjuring an emotional reaction.’ And it points to how the land and sea are interdependent parts of the total environmental balance: for example, more than half the oxygen we breathe comes from marine photosynthesis. As for the coral they will host, Comte was impressed by the conservation the Alligator Head Foundation is doing, which has significantly increased biomass and species diversity. And the many local coral varieties caught Comte’s eye. ‘It’s the shapes that attracted me’, she says, ‘I didn’t even know they were animals! I’m fascinated that though they’re animals, they support all this biodiversity, like a tropical forest would do on land.’ Near her sculptures is a nursery for coral, which she also loved: ‘It looks like clotheslines where the baby corals are able to grow. I like this idea that, for visitors, you don’t dive just to enjoy yourself but also to learn something about the ocean.’ Of course, it is not a simple matter – especially in 2021 – to go snorkelling in the Caribbean, but Comte’s current digital solo exhibition Dreaming of Alligator Head plants her underwater sculpture park in Berlin’s Köenig Galerie, allowing visitors to experience the underwater world without having to go on a physical journey.

Turning to natural history and associated science, corals are complex beings that play a key role in preventing coastal erosion and the production of oxygen for the ocean. Their potential extinction would have a deep impact: without them, many species would be threatened by both habitat loss and oxygen shortage. Shallow water, reef-building corals have a symbiotic relationship with the photosynthetic algae zooxanthellae, which live in their tissues, producing carbohydrates that the coral uses for food, as well as oxygen. Zooxanthellae also contribute the beautiful colours: they contain a pigment called chlorophyll which turns the coral green or brown, and that can change to blue, violet or red in response to different light conditions and water temperatures.

Southern hemisphere coral cover is typically declining by around 1% per year, a function of the extent to which coral loss outweighs growth. Both occur naturally, but the balance has been disturbed. The factors vary between reefs, e.g. predation by the crown-of-thorns starfish accounts for 40% of Great Barrier Reef losses but does not apply in the Caribbean, whereas coral diseases have a comparable impact in the latter but not the former. The other main Caribbean factors are storms, together with a phase shift from coral to algal dominance due to the loss of major groups of herbivores. Proposed solutions are not just global action on warming, but local and regional cooling and shading, assisted coral evolution, assisted gene flow, and measures to support and enhance coral recruitment. Comte’s project is an example of action to improve the balance of the equation by increasing growth: Denise Henry (Research Manager at the Alligator Foundation) explains that the Foundation has nurseries in which coral is grown to a size suitable to move out and replant. Replanting staghorn coral around the cacti not only provides a good place for it to grow further, its thickets also ‘mimic the flora you would see in a desert, and that also creates a habitat of intertwined forms that particularly suits fish’.

In her most recent exhibition in Madrid, Comte showcased the entire body of sculptures she had produced in Jamaica within an immersive ‘underwater’ landscape that incorporates a wall painting and video installation. Logically enough, this features wooden coral displayed on land as a complement to the concrete cacti displayed under water. This exhibition is divided into day and night spaces. The former presents the corals made of wood, while the latter evokes the darkness of the seabed’s depths.

The aims of Comte’s coral project are to improve the sea environment directly in a small way, and to persuade people of their duty to the sea. Chus Martínez has framed that dramatically in introducing recent TBA21–Academy projects: ‘Think about the Ocean as you think about a relationship. We know that humans are bad at being faithful, infidelity has a tenacity that faithfulness can only envy. If you ask about Nature or the Ocean, everyone would be ready to declare their love, or our dependency, and yet we cheat on the seas, on water, on resources, on the images, on life.’ Comte’s consideration of coral is both a practical contribution and a salient example of how to keep faith.

Please find more information about Claudia Comte and her After Nature exhibition at the Museo Nacional Thyssen Bornemisza here.

All images shown courtesy of Claudia Comte and TBA21–Academy