06 INSIDE THE MIND: NORAH ZUNIGA SHAW

Norah Zuniga Shaw (ZShaw) is an artist and director for performance and technology projects at the intersection of body, ecology, collaboration, and liberation. She holds a BA in Dance and Environmental Science from Hampshire College and an MFA in Dance and Intercultural Collaboration from UCLA’s World Art and Culture.

As a teaching artist based at the Ohio State University (OSU)’s Advanced Computing Center for the Arts and Design (ACCAD), she teaches courses in interdisciplinary research and composition, intermedia performance, critical theories of the body, performance and technology, curation, embodied digital literacy, and dance improvisation. For the past two decades, ZShaw has also been Professor and Director for Dance and Technology at OSU’s Department of Dance.

In her own work, ZShaw explores a wide range of mediums and genres, from live sound and movement performance, to data visualisation, interactive media installations, virtual reality, writing, artist walks, and participatory theatre. Her projects tour internationally and she has spent many years in the dance discourses and practices of Costa Rica, Germany, and The Netherlands.

In this conversation, which unfolded through written correspondence, we discuss ZShaw’s intercultural influences and the creative processes underlying her work, considering themes such as movement, perception, community, social change, and care.

Dwaynica Greaves: Many rich themes and influences shape your creative process. What is the foundation of your work and how do you approach your creative process?

Norah Zuniga Shaw: Foundation is an interesting word and I feel some resistance to it. The idea of foundations is often used to support western, modernist notions of linearity and progress. I find life and art much messier and more emergent than that, like the mycelial networks that are enjoying such a renaissance in contemporary thinking, or the branching, spiralling, connecting, re-connecting, doubling back, off-shooting, nodes and bulges of potato sprouts and other rhizomes ala Deleuze and Guattari (Deleuze & Guattari, 1980).

Like many artists, I have a constellation of interests that delight and animate me, and they absolutely relate and recur, but they also resist easy categorisation. Recurring themes include technology, ecology, equity, community, love, loss, hope, movement, diversity, complexity, collaboration, and liberation. I love discovering connections between seemingly disparate ideas – a proclivity that was nurtured through my own curious mix of experience, including a background in science and dance and years working as an artist in a technology research centre. Training in both choreography and estuarine ecology tuned my eyes and thinking to pattern recognition.

All my successes are the result of fostering the collective intelligence of generous, diverse teams, so facilitation and collaboration could be seen as foundational. I value complex, polyphonic contexts with diverse perspectives that come in and out of alignment, resisting unison in favour of more dynamic structures. I often find myself acting as translator between ideas, people, and forms and I’m happiest in a state of collaborating generously and fostering communities who give this to one another.

My work comes into the world through many different forms: movement and sonic improvisation, interactive systems, digital media, graphics, animations, choreography, writing, and social practice. I am interdisciplinary to my core, and at the same time my deepest disciplinary training is in dance and improvisation, so movement, physical inquiry, choreographic thinking, and sensation or experience are always a part of my work. It feels important to hold space for bodily experience and well-being in our current techno-scientific life world.

I approach creative process as inquiry, so there will be different animating questions in different works with changing content. Over the years I have increasingly come to trust the emergent process and have learned to hold back on my natural inclination to shape things, organise, and recognise structure. I still use those compositional skills, but I delay them in the process. This makes space for delightful leaps of insight in more iterative processes, grounded in inquiry. I frequently work from questions as starting points and the trick is to stay with the questions even as the work begins to take shape. It is an approach to research that I really value and have learned a great deal about from colleagues in design and in the sciences.

DG: Improvisation is among your constellation of interests. What does building creative work upon the idea of improvisation mean to you and how do you demonstrate this in your practice?

NZS: Improvisation is life and cultivating the skills of an improviser enhances life, particularly in the unstable and rapidly changing contexts of current conditions on the planet. Other words and phrases that describe improvisation for me include spontaneity, but also concentration, forms of attention, art of perception, mindfulness, radical presence, and emergent systems. Improvisation is much more akin to how natural systems live and grow. It is also aligned with contemporary technologies, so studying improvisation can help people comprehend and deal with the algorithmic nature of our technologies and even machine learning, which is, of course, the basis of much of the artificial intelligence getting so much attention right now. Improvisation is akin to the ways in which natural systems live and grow.

In dance improvisation, we have a practice of developing scores that guide and support spontaneous creation. Scores can be lists or instructions, or just an idea that gets things started. They are containers for creative play and can be planned or emergent. Scores can be elaborate or beautifully succinct, as in Nina Martin’s ‘one idea scores’ (Martin, 2014), where simple rules produce elegant complexity and insights into group dynamics. One score of Nina’s that I often use with my students is to have five people stand in a line. They may turn front or back, but they cannot look at each other. The system as a whole needs to keep moving and they must keep two facing front and three facing back at all times. It is possible and impossible, but that is also not the point. It is so beautiful to observe, and I love the insights people have watching or doing the score. Nina does this score for dance training and composition, but I’ve also found it really helpful for teaching digital literacy and algorithmic structure, as well as social dynamics, personal responsibility, and awareness (Martin, 2007). That’s why I love improvisation – it reflects and enhances life!

DG: Is improvisation explicit/implicit to the recipients of your work or is it explicit/implicit in the creation process?

NZS: I improvise because I value the ways in which it connects me to the broader capacity of my bodymindspirit and expands my creative palette beyond solely the conscious decision making of more top-down composition. I value the way this cultivates a deep attention to listening, responding, and risk taking. I work with dancers and musicians who are very experienced improvisers. It is both something that anyone can do anytime, and a skill that can be developed with great nuance.

Like most improvisers, I’m interested in cognition and the bodily knowledge accumulated over decades of practice, but I’m also curious about the intuitive impulses and leaps folks make in the moment, when given conditions and containers for free play. In my performance projects, this is sometimes a known part of the process. For example, in Climate Gathering, when audiences provide their names and climate memories prior to entering the space and I then memorise these details and use them as a score to ground me during the improvised performance. In this instance, the improvisational elements are transparent; the audience knows the performance is different each time because their names and memories are present in the work. It is also clear because in those works – which we sometimes call transmedia performance rituals – there are multiple tasks offered to the audience participants to invite them into co-creating with us and we respond to what they do though shaping the sound in the room, or the set, or writing in chalk on the floor, and so on.

I think improvisation can be a pleasure to witness, even if you don’t know it is present, which is often the case in contemporary performance. Choreographers will use improvisation to generate a certain state in the performers, or to keep a composition alive and shifting, and you don’t need to know that it is generated spontaneously to enjoy the effect it creates. The same questions arise in interactive media projects and the same spectrum of responses is possible.

DG: ‘Paradigm shifting’, ‘genre-bending’, and ‘spacemaker’ are phrases that are used to describe your work. Why do these phrases resonate with you? What do you want the recipients of your work to learn about the way you create?

NZS: ‘Paradigm shifting’, ‘genre-bending’, and ‘spacemaker’ are all terms of liberation, freedom, non-violent disruption, mobility, and shapeshifting creativity, which skips social categorisation, such as ‘genre’ or even ‘paradigm’, in favour of something more immediate and more fluid. I love their queerness and I hope participants in my work and audiences are invited into their own capacity for liberation.

In my life and work, I am always working and aspiring toward queer feminist, anti-racist, ecologically entangled, collaborative values and practices. I’m not interested in hierarchy, nor in making anyone do anything – that would make me a dictator. I’m surprised how many organisations and systems are predicated on making people do things, on compelling people, rather than inviting them. So, when I’m in positions of leadership, for a big project or in the classroom, in a workshop, or a community convening, or even when I am asked to give an artist talk, I’m starting from a place of invitation. I know that I can’t completely undo all the ways that power and privilege circulate and the injustices and inequities at play, but I can always be in a practice of shifting, revealing, listening, and undoing.

‘Spacemaker’ is what my students call me and that’s probably because I’m interested in carving out spaces within our institutional lives for people to do what they want to do. As the brilliant poet, activist, and author Alexis Pauline Gumbs (2024) says: ‘the institution is not my project‘. People and their transformative potential on a planet in need – that’s what really motivates me. I’m interested in knowing what has heat and energy for you. What you really want. Let’s follow that, rather than what you think you should be doing, or making, or finishing, or thinking. Listen and sense for what wants to be known and consider letting the rest go.

DG: Community and collaboration are core values in your artistic practice and in Upwelling you created a ‘nourishing community during a period of isolation and uncertainty’. Could you tell us more about this project and why you chose an audio-visual medium?

NZS: Upwelling started out of a simple necessity to be in community with people I love during COVID-19 lockdowns – a time of isolation and anxiety. I didn’t choose a medium so much as I followed an impulse to connect and a long-standing interest in artist walking practices, radio ballets, audio dances, correspondence, and generative archives. I had been talking with several friends on the phone to support each other during the anxiety, fear, and isolation of early COVID lockdowns and saw the opportunity to weave us all together in a creative community of trust and support. I called it ‘artist friends entering into exchange of audio diaries during the middle days of pandemic’ and I asked people to ‘leave a trace’.

This is part of emergent process, or iterative, bottom-up practices. I start with an impulse, question, or problem, and initiate some creative response in relationship to it, then quickly begin asking questions in collaboration with others. I wrote a post on my newsletter about this: what do you do when you don’t know what to do, ways to get started (https://livablefutures.substack.com/). It is a fun one.

It wasn’t until a year later, when May came around again, and I was wanting to acknowledge and reflect on the year that had passed, that I returned to the videos and audio and started intuitively knitting them together, as a kind of gift to give back to the people who had created them. Once I started this process, I could feel a sense of story, but I didn’t want to fall into the traps of conventional narrative structures, which have been weaponised by marketing and Hollywood. I had a question about a kind of ‘storyness’, as Bebe Miller says, which is responsive to the people and materials at hand. I reached out to other creators and had some amazing conversations with animator Vita Berenzina-Blackburn about Maya Deren’s film poems and feminist storytelling, and about stories which meander or move in circles, spirals, or happen in little bursts (Alison, 2019). I think that, unknowingly, I was healing my relationship to stories by reclaiming them from the mainstream arc of set up, conflict, and resolution.

Over time, I just kept weaving together these little pieces and it became a fourteen-minute short film. At the time, Vita was working on her own animations and they eventually became part of the film, providing a powerful mythical presence in the work. I sent the film to the people who made it with me, and I thought that would be the end of it. I like creating artworks for specific audiences sometimes and resisting the push to always make something to be seen by the masses, but when I sent the film to its co-creators, they told me it needed to be shared more publicly. That led me to develop the work further for museum and gallery contexts and as an anchor for public dialog. I’m grateful for the help of a residency at the Wexner Center for the Arts and for the public premiere there in 2022.

The Wexner curators wrote about the work: ‘Upwelling offers a restorative beacon of presence. Created over the intervening period and now viewed from almost two years later, the project can be seen as an act of care and remembering, or as the artist describes it, “a form of memory work, a way of recalling, deconstructing, to understand and to remain in the moment of planetary need and urgency”. Upwelling’s gathered recitations and incantations create a collective register of a transformative moment on the planet – together, in short, they leave a trace.’ (Wexner Center for the Arts, 2022).

Since then, I have developed an ongoing memorial practice to remember and recognise the significance of the pandemic in our lives and the reckoning with racism that happened during that time. I’m committed to sharing Upwelling in May every year and to generating dialog with it through my newsletter and social media.

DG: You have also explored data as a component in your work. For example, in your work Synchronous Objects, you combined dance, data, and objects. Could you describe which components of each form (dance, data, objects) you took to create this project, and explain how you fused them together?

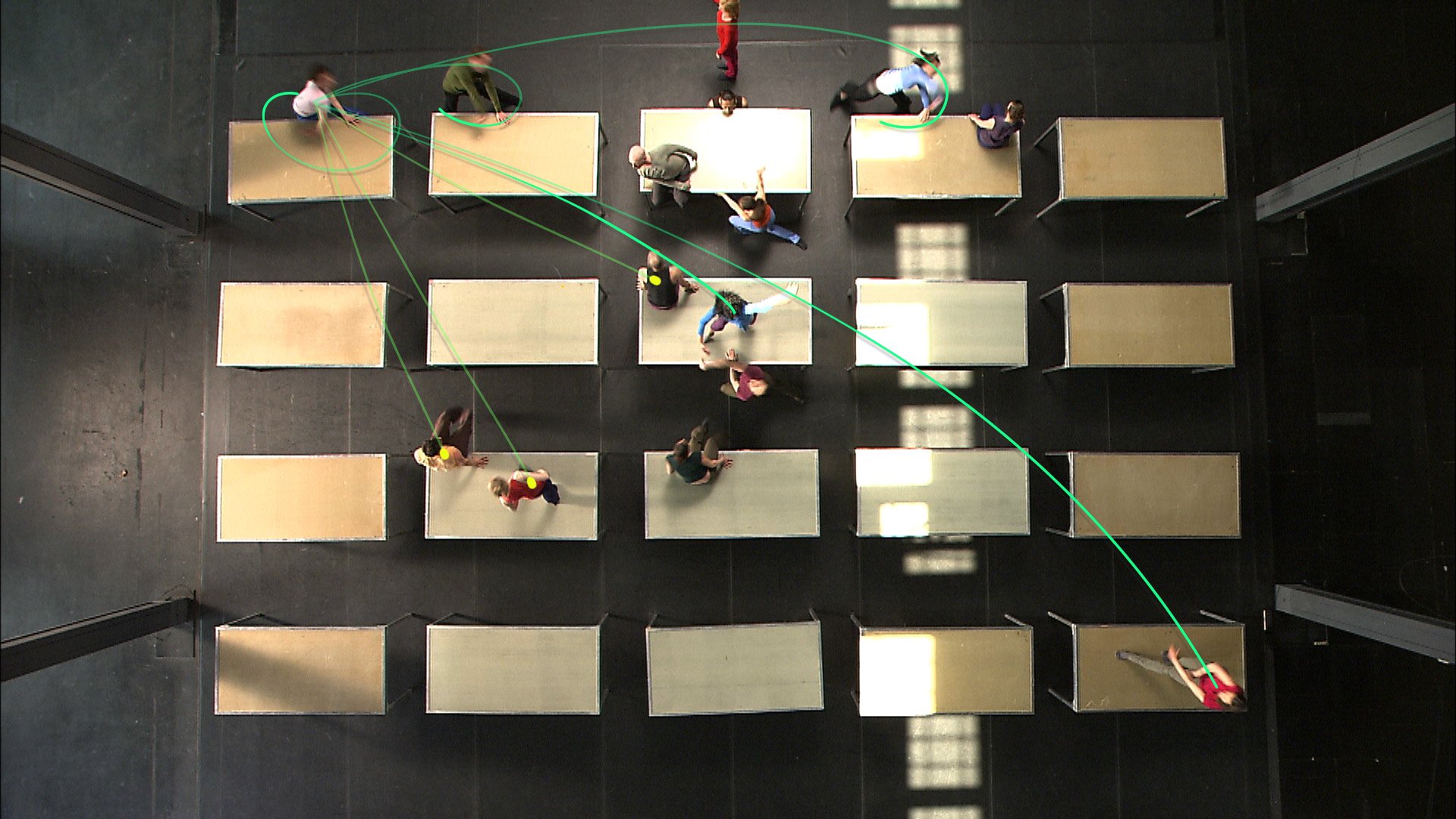

NZS: It is more of a flow than a fusing of elements. Synchronous Objects (Forsythe, Palazzi, Zuniga Shaw 2009) flows from dance to data to objects (animations, graphics, software) in a process we call ‘choreographic visualisation’. Choreographic visualisation is a term we coined (Bleeker, 2016) to describe a practice we were inventing at the time – a process of revealing deep structure in performances, to extend them beyond the live experience and invite others into richer understandings of embodied knowledge. Some of the most important work that these projects have done is to place physical intelligence at the centre of interdisciplinary discovery. I’ve toured with Synchronous Objects for over a decade and met the most amazing people doing all kinds of rich and complex work in the world.

Collaboration is at the heart of the project. I created Synchronous Objects with choreographer William Forsythe, animator Maria Palazzi, and more than thirty other amazing contributors and collaborators from computer science, dance, design, statistics, geography, architecture, and other fields of inquiry. The project starts from a ballet by William Forsythe called One Flat Thing, reproduced (2000) which he created with his company long before we started working together. He brought the piece and his instigating questions to us and what we created emerged from the iterative practices of a community over time.

Synchronous Objects was launched in 2009 as a screen-based, interactive media project published online and available as open-source resources. It comes from the working practices of the Ballet Frankfurt and the Forsythe Company and starts from the question: what else might this dance look like?

Methodologically, we invented a research process that began by considering the dance as a choreographic resource (a term Scott deLahunta and I explored in some early writing on our process) (deLahunta, Groves, Zuniga Shaw, 2008). This move decouples the choreographic idea from the dance in ways that are both exciting and frightening to folks who are afraid of losing bodily expression, and I understand, but we consider it an addition, rather than a replacement.

Flowing from dance to data to objects requires thinking of the dance as a choreographic resource; it could be any complex movement phenomenon and at the same time it is totally idiosyncratic and specific to those who made it. Moving to data is a process of prioritisation – some things are gained, and others are lost. In our case the data is driven by the artist and the dancer’s interests and intent.

DG: In your 2008 essay with Scott deLahunta, ‘Choreographic resources: agents, archives, scores and installations’, you open with the statement that there is a ‘well-debated tension existing between the live dance performance and its documentation or recording.’ Why is this so? Why is there an argument that ‘dance should be continually disappearing?’

NZS: The issue is simply that dance is a live artform and it is therefore always in a state of disappearing. This can be a special and valuable thing – impermanence, or non-attachment to form, or object, or ownership – but it can also be something that keeps the artform marginalised, so folks debate the values across that spectrum. Of course, any live form has these problems, as do installation arts, but music has its scores, and theatre, its scripts. Over the centuries, people have invented various forms of notation to try to represent choreographic works and keep them alive in the repertory and these are similar to musical scores. Oral history has also played an important role, as has the practice of dancers teaching the dance to the next performer. There are many forms of transmission and, of course, film has been used and when video was invented it made capturing moving images much more accessible. This became part of dance documentation, but, as people will sense intuitively, the document is not the original (there are entire libraries of philosophical thinking on this) and there is something in liveness that does not come through on the page, the screen, or through talking about it.

With Synchronous Objects, we started from a different place. We didn’t try to document the live performance of the work for repertory or preservation, although we did have some great video. We acknowledged liveness as a fundamental problem in the digital era and worked instead with what else is possible; it is more of a ‘yes and’ project than an ‘either or’. YES, there is nothing that can replace the live AND then what else might physical thinking look like? What other parallel virtual manifestations can come from choreographic structures? What if we translate both quantitatively and qualitatively through information graphics and animation? What new relationships can be created and how can dancing ideas be taken up and understood more broadly? And so on.

That’s why generating data was so important and we brought a very careful politics to how we generated data from the dance, prioritising the perspectives of the choreographer and dancers rather than outside analysis. We did bring our own perspectives, of course, and generating data offered some fun insights back to the dancers, but the data is much more human and handmade, and that is very intentional. We resisted the common practice of creating a singular authorial score of the work in favour of multiplicity. The work has circulated in many interdisciplinary conversations on digital archives, data visualisation, the aesthetics and politics of information, humane technology, and data humanism, and I always enjoy these communities of practice.

DG: Thinking about liveness and how this links with audience interaction, could you tell us more about your work OASIS, what inspired this work, and why immersion was vital to the experience?

NZS: I’m interested in the relationship between immersive technology and care, more precisely, healing. I would like to see more immersive technology used for well-being, healing, open ended creativity, and full-bodied movement. OASIS is part of my larger project Livable Futures (2018). This piece started in March of 2022, when there was so much fatigue and unacknowledged grief and loss from the pandemic, so in asking the question, ‘what performances are needed now’, the themes of rest, recovery, and respite all just emerged together. At the same time, I was and am experiencing disabilities because of long-COVID and one of the only things that is helping is learning to pace myself. I made this a research question for a commission I was offered: what is pacing in intermedia spaces? If we prioritise pacing and humane rhythms of rest and activity during a commission (usually very intensive periods of work), what wants to be made? I want to acknowledge that there is longstanding work by Black artists in this space focusing on BIPOC experiences and livability in a racist world; I’m thinking about adrienne maree brown’s Pleasure Activism (brown, 2019), the Nap Ministry, and other ‘rest as resistance’ movements.

In our case, we are looking at oasis ecologies as literal and figurative metaphors but also teachers of resilience drawing attention to nuance, delicacy, and vibration. I have a long-term interest in geothermal sites and other spaces of change and transition, such as estuaries and the liminal layers of alpine lakes. I have been studying some of these geographical features since doing my undergraduate work in ecology, but I study them as an artist and amateur naturalist more than anything else. In 2022, I went to Agua Caliente Cahuilla indigenous land in what is known as Palm Springs, and I found the oasis ecologies and indigenous perspectives there very important to thinking about delicate ecologies, stewardship, and reparations.

The piece is full of colour, water, sound, stories, and poetic, stargazing dream states. I’ve put together a series of videos that vibrate and oscillate in resilience patterns and these are shown on screens placed like rocky crags or tide pools around the space. Resilience movement is something I’m always thinking about. My collaborator and friend, composer Byron Au Yong has developed a beautiful song cycle for the work, drawing on his experience in Chinese and Korean vocal traditions as well as musical theatre and my own background in hippy sing-alongs and Buddhist/Jewish interfaith practices. The song cycle is a score for our improvised performances, and it integrates audience contributions from their own childhood songs and lullabies so that, by the end, we weave a new communal soundscape each time. I also tell the stories differently each time, tuning into the sounds that the participants are making. We use live sound processing software created by Marc Ainger, an acousmatic composer. Recently I’ve been working with queer feminist dramaturge Michael Morris on the connections they see between our work and the myth of Orpheus and Daphne. I am reading and re-reading Rilke’s Sonnets to Orpheus (Rainer Maria Rilke, 1922), and am finding non-linear story structures within that I can improvise with and connect to stories provided by the audience.

We think of this as our faux-asis and we are also exploring a virtual reality version with visual artist Jameel Paulin, who does amazing afrofuturist work. There is still so much to discover about performance and movement in virtual reality. A generous curator friend of mine called it a ‘mixed-reality opera’. I like that. I’d love to do this work for specific groups who want to rest and renew together like healthcare workers or an interfaith community or a women’s group. I like thinking about audiences in this way and developing the work responsively with them.

DG: In your projects, Climate Banshee, Hound, and Humane Tech Deck, you explore ways of improving wellbeing and what it is to be humane. In your opinion, what is it to be humane?

NZS: I think we know it when we feel it. When we are in humane conditions, we feel supported, free, and acknowledged in our wholeness and dignity. In that way, I think contemporary performance that acknowledges our awkwardness and even ugliness, and the shadows in our lives and selves, can be incredibly humane, because so much of our lives is focused on the appearance of strength, health, beauty, and having it all together. But it needs to be done with an ethics of care, and in developments such as the movements for algorithmic justice and data humanism, the emphasis there is on agency and control over our data and using it to enhance well-being, rather than on furthering marketing agendas and surveillance.

The Humane Tech Deck is a set of conversation cards I created with many collaborators as part of a larger initiative I led in 2016 called the Collaboration for Humane Technology. During that project, we explored ways of defining humane technology. This was a challenge, but all of our conversations included technology that does no harm, that foregrounds justice, bodily awareness, meaningful social exchange, care, and open-ended creativity. With the growing focus on algorithmic justice and the potential dangers posed by allowing the internet to evolve the way we have, and with advances in AI, virtual reality and augmented realities, there is a renewed sense of the importance of these questions and possibilities.

In all my work with technology, I am seeking humane technological approaches that resist many of its potentially dehumanising effects. Given the limits of traditional, screen-based, cinematic approaches for immersive and open environments, I think the expertise developed through live performance and installation arts will be particularly valuable as technology develops in future, alongside disability rights activism and the world of accessibility awareness. If things are more accessible, they are also better for everyone. The Ford Foundation is doing some good work in this space, and I am enjoying Alice Wong’s and others’ work on disability visibility and CripTech, but ‘humane’ also needs to be remade in a more-than-human way, so that we are talking about the full spectrum of life on the Earth – as Katherine Hayles said in her prescient work on posthumanism from the 1990s, the full spectrum of life is ‘biological, human, and artificial’ (Hayles, 1990).

DG: You also highlight ‘the problem of the human’ in your Livable Futures project and newsletter. You ask the question: ‘what are you centering in your life?’ Could you explain what centering is and why it shapes who we are?

NZS: The ‘problem of the human’ is the high level of self-involvement demonstrated by our own species. Decentering humans doesn’t mean being anti-human, rather it means re-orienting ourselves within the spectrum of life on Earth. Indigenous peoples around the world have been living and speaking about this for millennia, and they still are. I highly recommend Donna Haraway’s Staying with the Trouble (2016) and Patty Krawec’s new work, Becoming Kin (2022), if you’re interested in thinking about this in relation to the history and present of settler colonialism in the US, but also colonialism more broadly. So, the work is about centering, but it is also about decentering.

I like the word ‘center’ because it is choreographic – it suggests movement. It is an orienting word, suggesting that we can always change what we are oriented toward, which makes me think of the beautiful queer phenomenology of Sara Ahmed (Ahmed, 2006). In fact, when I teach the Liveable Futures practices, I usually start with two other practices first: arriving and turning toward. These include arriving into presence by noticing what we notice, tuning into sensation, turning toward the things we are turning away from, usually our fears, and then doing an inventory of what we are centering. Perception is how the world comes into focus for us and what we focus on grows in our experience. You could also say, who you are surrounding yourself with and what you are listening to. To paraphrase Austin Kleon and Maya Angelou, you are a mashup of what you let into your life, so be careful who and what you surround yourself with – it matters. This is also true in anti-racist and queer feminist work. Seek out ideas and people who nourish and challenge you, and work to increase the amount of time spent listening to historically marginalised voices and to the more-than-human world. By doing this your life changes, your perception, assumptions, and actions change. Humans are social beings.

DG: Centering/decentering are some of the meta practices you have developed during your establishment of the Livable Futures project. Could you tell us more about this work? What inspired it and what are its core values?

NZS: Livable Futures is many things. It can be understood as a network, a community of practice, a series of performances and exhibitions, and a mode of inquiry. It has also become a workshop, a course, a performative lecture, a podcast, and a newsletter. It is always evolving. It began in 2016, developing out of another initiative I was facilitating at the time. We were wrestling with the term ‘humane’ and the ‘problem of the human’ as I discussed earlier, and the mainstream tendency to set ecological and technological ideas off against each other. We had a symposium that we called Livable Futures in 2017 and people really responded; they wanted to be thinking, creating, and turning toward the fears, anxiety, rage, and magnitude of the climate crisis and the ecological conditions of uncertainty and inequity, and this was before the pandemic. The desire for transformative community and change is even greater now and the need for both hope and time for grief is evident. The future is unknown and in that there is hope and space for action.

Overall, Livable Futures fosters creative responses to survival under conditions of unpredictability and crisis. Our projects are collaborative, inclusive, and socially responsive. We choose to orient around the term ‘livability’, as opposed to ‘sustainability’, because it reminds us that we cannot and do not want to sustain the extractive practices and inequities of life as we know it. In contrast, ‘livability’ is a term which encompasses social justice and ecological ethics by inviting critical rethinking about who survives and who gets to thrive in our communities, near and far, and extends that consideration to non-human and artificial life, now and in the future. This also acknowledges that technology is both part of our lifeworld and that it must be part of the work at hand.

DG: In your blog post welcoming everyone to the Livable Futures project you wrote that you ‘decided to return to performance after years of mostly creating digital works’. How does creating a live performance differ from creating in a digital medium?

NZS: I really love the immediacy of performance and the ability it gives us to create cathartic, charismatic, and transformative states with other people. I love the way liveness calls us – our biggest selves – into presence. Digital works allow for greater distribution and circulation and have wonderful interdisciplinary resonances. Performance is more immediate and the pieces I’ve been making in the past several years usually involve small audience groups (ten to twenty people at a time), so that we can really focus on the intimacy this enables, and on facilitating co-creative experiences.

For me, performance works start from sensation and bodily presence, and, when dealing with seemingly insurmountable issues like climate change, I find it is helpful to bring them into the scale of my body. Our bodies. I find my audiences and I are more able to do the work at hand if things are brought into the scale of our liveness and experience. I call it ‘feeling into intention and action’, and it is a way around powerlessness and apathy. For example, in our Climate Gathering transmedia performance ritual, people begin with a climate memory and are then invited to share through writing with ice or chalk on the floor. Then they hear their name and their strengths called out and they are invited to move and make sound, and, slowly but surely, climate change is moved from just a frightful outside force into something they can turn toward. One audience member called it ‘facing the magnitudes’.

DG: Returning to the medium of dance, research (Vicary et al., 2017) has shown that interpersonal synchrony in dance gives cues for pro-social behaviour. In your blog post, ‘Sustaining Practices (2021)’, you explore the topic of interpersonal synchrony in dance. What is a ‘sustaining practice’ and why is dancing in a community one of your constant shared practices?

NZS: I love it that there is increasing research these days which supports things that we know intuitively. Humans are sustained and nourished by movement of all kinds and by being in relationship with other humans, especially in contexts that are playful and safe. When I move, I find joy. When I move in playful, open-ended ways with others, I find communion. When I move spontaneously, I listen to myself and find inspiration from the choices others are making around me. I am grateful for the increased resources online for dancing with others – although I do love in person whenever possible.

Sustaining practices are the things we do day to day that help us to feel grounded, nourished, and alive. When we acknowledge them as practices, rather than habits or routines, they can take on bigger importance in our lives – as rituals with intention – and we can develop and share them with others. For example, I have always loved to read. When I hold reading as a sustaining practice, I start to think about how I read, and when, and what different reading practices do, and I can share this with others. I wrote about this on Medium once because I think people often approach reading as either an escape or a chore and there’s a lot loaded into it, but there are reading practices that can really make it blossom in your life as a way of supporting well-being. I sometimes work with reading as prayer, as in the lectio divina of Catholic monks, or as a playful practice of dipping into books at random, like tarot or divination, or linear reading, where I read every single word of a book but only as much as I want at a time (sometimes I read only one sentence). I also really love adrienne maree browns’ offering that perhaps what we need is just the idea of a book and we don’t need to read it at all (Brown, 2019). Reading as a practice invites me to notice when I do it during the day, what works best, and to make an intentional choice about this that can be repeated. That might mean every morning with my tea, or maybe a Friday night reading practice. Follow what feels good. If you have a ‘full body yes’, as my mother says, then you are probably in the space of a sustaining practice. If it doesn’t feel good, don’t do it.

The pandemic was a big teacher for all of us about sustaining practices. Consider what you did during the pandemic to help you deal with the pressure and anxiety and stress. What made life more livable? How can you keep practising this in your life today and share it with others? I noticed during the pandemic that if I read first thing in the morning, it kept my brain in a slowly-oscillating, peaceful state and it inspired creative thinking. I also found tending my houseplants important, and walking, collaging, and, of course, journaling. It doesn’t need to be anything fancy or unusual, just sensing into your own experience and listening to what you find there. I think even asking the question and expanding the space in our consciousness for these considerations can do good in our lives. What are the practices that are sustaining you? What does support look like? What forms of more-than-human support are available in the world around you? How can you expand their presence in your life and inspire others to do the same?

DG: Remaining on the topic of well being and linking it to your ideas on better futures, I’ll end this interview on the question you present in Humane Tech Deck: ‘What are your creative actions for better futures?’

Seth Godin once said, in reference to dealing with the challenges at hand, ‘we are all called to be artists, to create in ways that matter to other people’ and that is a kind of mantra for me (Tippett, 2013). Livable Futures is one giant, iterative, ongoing, multivariate set of actions for better futures. I’m so grateful that the project has grown organically and to the people involved. I am always experimenting and trying new things. I developed a course at the university to support students taking creative action for livable futures and we have twelve beautiful new student fellows creating projects on foraging and family history, the relationship between climate science and spiritual practices, decolonizing cartography, feminist experimental film on gardens and communities of care, adaptive dance, photo essays on Black feminist futurisms, non-fiction about listening and noticing as sustaining practices, and so much more. I am inspired and uplifted by them every day and we will be sharing more about their work on the Livable Futures Idea Archive on our site.

I’m working on extending this to an online course that is open to the community. In that spirit, I’ve also started a Livable Futures newsletter on Substack and a second season of the podcast to open the project for more folks who want to think, create, and enter into community with us. I really love the conversations that the newsletter and podcast support; there is so much wisdom in the world and artists are full of energy and ideas that we can all benefit from. Artists are accustomed to dealing with the unknown and can be valuable guides, especially for practices that are sustaining and new approaches to activism.

I’m also developing a performance lecture for Livable Futures as an interactive public dialog and shared the first version of it with colleagues and students in Costa Rica this year. We are always creating Climate Gatherings for communities that want new ways to confront eco-anxiety and that want to take part in transformative dialog around the climate crisis.

And slowly but surely, we keep developing virtual and augmented reality components for OASIS to support communal rest and recovery. Andre M Zachery, Very Cleaver Studios, and I have completed an audio walk / radio cypher for reconstituting public space with social and ecological justice perspectives, to be danced by anyone, anywhere, through audio guidance. I hope to get that out soon.

I’m healing myself. I have been dealing with long-COVID and this has been a powerful teacher for me on disability and pacing, slow time, and more humane rhythms of activity and rest. And I am raising a son who is now becoming an adult and doing his own beautiful work to become part of tikkun olam – repairing the world. I am so grateful.

For more on Norah Zuniga Shaw and her work, please visit https://nzshaw.art/ and https://livablefutures.substack.com/

All images shown courtesy of the artist ©️ Norah Zuniga Shaw. All rights reserved.

References:

Ahmed, S. (2006). Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others. Durham: Duke University Press.

Alison, J. (2019). Meander, Spiral, Explode: Design and Pattern in Narrative. New York, NY: Catapult Press.

bebemillercompany.org. (n.d.). Bebe Miller, Artistic Director | Bebe Miller Company. [online] Available at: http://bebemillercompany.org/about/bebe-miller/ [Accessed 5 Apr. 2024].

Bleeker, M. Editor. (2016). Transmission in Motion: The Technologizing of Dance. London: Routledge Press.

Brown, A.M. (2017). Emergent strategy: shaping change, changing worlds. AK Press.

Brown, A.M. (2019). Pleasure activism: The politics of feeling good. Chico, Ca: Ak Press.

DeLahunta, S. and Shaw, N.Z. (2008) Choreographic resources: agents, archives, scores and installations. Performance Research: A Journal of the Performing Arts, volume 13 (1): 131-133. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13528160802465664 [Accessed 5 Apr. 2024].

Deleuze, G. & Guattari, F. (1980). A thousand plateaus: capitalism and schizophrenia. Translated by B. Massumi. London [U.A.] Bloomsbury.

Forsythe, W., Maria Palazzi, Norah Zuniga Shaw. (2009). Synchronous Objects. [online] Available at: https://synchronousobjects.osu.edu/ [Accessed 5 Apr. 2024].

Forsythe, William (2008) ‘Choreographic Objects’ in William Forsythe: Suspense. (Catalogue from exhibition at Ursula Blickle Stiftung, Kraichtal 17 May– 29 June 2008), Zürich: JRP/Ringier.

Gumbs, Alexis Pauline. (2024). Now. [online] Available at: https://www.alexispauline.com/now [Accessed 5 Apr. 2024].

Haraway, D. (2016). Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Hayles, N. K. (1990). Chaos Bound: Orderly Disorder in Contemporary Literature and Science. Cornell University Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7591/j.ctt207g6w4

Krawec, P. (2022). Becoming Kin. Broadleaf Books.

Martin, N. (2008) Ensemble Thinking: Compositional Strategies for Group Improvisation. Contact Quarterly, Summer/Fall 2008, pp.10-14. [Accessed 5 Apr. 2024].

Martin, N. (2014) Emergent Choreography: Spontaneous Ensemble Dance Composition in Improvised Performance. The Texas Women’s University. https://twu-ir.tdl.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/26f799ae-6ade-42d4-8d9c-8b0b2ab9ce00/content [Accessed 5 Apr. 2024].

Rilke, R.M., (1922). The Duino Elegies & The Sonnets to Orpheus. Vintage (2014).

Tippett, K. (2013). [online] On Being: Interview with Seth Godin: Life, the Internet and Everything. https://onbeing.org/programs/seth-godin-life-the-internet-and-everything-sep2018/ [Accessed 5 Apr. 2024]

Vicary, S., Sperling, M., Von Zimmermann, J., Richardson, D. C., & Orgs, G. (2017). Joint action aesthetics. Plos one, 12(7), e0180101.

Wexner Center for the Arts, (2022) Website content for premier of Upwelling. [online] Columbus, OH. https://wexarts.org/film-video/norah-zshaw [Accessed: 08 April 2024].

Zuniga Shaw, N. (2021) Sustaining practices, NZShaw. Available at: https://nzshaw.art/2020/12/21/example-post-3/ [Accessed: 08 April 2024].

Zuniga Shaw, N. [online] Available at: Livable Futures newsletter and podcast. https://livablefutures.substack.com/ [Accessed 5 Apr. 2024].