05 INSIDE THE MIND: TALINE TEMIZIAN

The Game & The Acrobat, 2019. Film showcased at the FUTUREHERE live conference at the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence. Single channel film installation that includes artist’s own FMRI scans. Photo Credits: Studio Taline Temizian.

Taline Temizian is a London-based artist, with backgrounds in traditional fine art, literature, visual communication, performance and digital technology. Her main scientific interests lie in cardiology and neuroscience, with a focus on memory and trauma. Through multiple media, Temizian explores systems and signs with a view to creating interplay between personal narrative, futurism, trans-humanism, and cultural history. Particular emphasis is placed on the ways in which neurological activity contributes to lived experience and on questions about how it might be possible for artists to change the way we see the world – to shift perception and paradigms in pursuit of happiness.

Her work has been featured in a wide range of solo, collaborative, group shows, and curated collective projects, including at the Venice Biennale independent Projects, The CCA, Montreal, London Q Parks and galleries, The Historic Museum, Basel, The Contemporary Art Center & Museum of Modern Art, Yerevan, The Museum of Broken Relationships, Zagreb, The Java Art Centre, New York, MACO Museum, Oaxaca, in Tallinn, Dusseldorf, Berlin, Beirut, art centres and galleries in Brussels, curated projects Gent, and her work is also held in private and public collections, internationally.

In this interview, we discuss the processes and effects of memory and trauma, and look at the ways in which the artist’s own experiences shape her work.

Dwaynica Greaves (DG): Could you please tell us about your journeys into cardiology and neuroscience, and how these two fields feed back into your exploration of the human subject?

Taline Temizian (TT): As a child, I always asked myself – what is the brain, what is consciousness? What I was trying to figure out was my relationship to the world, to myself, and to others. These can be unpredictable relationships, and the uncertainty of being an artist is that you’re always trying to make order out of chaos, then break it again, which is very difficult. I’m interested in neuroscience because it might offer explanations to these questions.

My interest in cardiology stemmed naturally from my father being a cardiologist. I grew up reading his medical anatomy books and he often spoke about the heart, the brain, and the experiences of his patients. Later, in my adult years, I shifted between wanting to become a neuroscientist and psychiatrist, and an actor and architect, but my love for performance and investigating emotions always revolved around science. In essence, the main question I ask myself as an artist is: how can I understand and explain things with the medium that I have?

DG: Out of all the brain’s executive functions, why does memory stand out to you?

TT: Our DNA carries memories – a genetic blueprint, if you will. Traumatic experiences may leave chemical marks on a person's genes, causing epigenetic alterations which can then be passed down to future generations, in an attempt to prepare us for similar trauma.

Every experience, apart from the exact current moment, is memory. Memory is the trace of a thought, interaction, happening, or emotion. Our sensory perceptions of an event are, initially, encoded synaptically and they may be accurate, in part, but sensory perception is also partly subjective. Not only are our sensory bodies calibrated uniquely as individuals, we might also notice, or focus our attention on, certain elements of an event. Moreover, not all of the sensory information which is initially encoded will be transferred to and stored in our long-term memory. Our hippocampus and frontal cortex decide which memories to store[i]. All these variables, among others, mean that no two memories of an event, gathered from two different individuals, are likely to be exactly the same.

Memory is a blueprint or ‘brain-print’ which defines each of us as an individual. It is constantly regenerating data that makes any story of any given time a digital biography of us as humans. I work on understanding and depicting the ‘place of memory’. Scientific studies tend to focus on the trauma of sad experiences, but I struggle with trauma that comes from the endings of happy experiences, because I don’t want them to end. It’s very strange thinking about memory because the brain is constantly regenerating, reforming, and changing. I’m interested in the relationship between trauma and memory because I have lived trauma in all of its forms; the short term, the long term, the slow-motion, and the historical. Naturally, my historical starting points are not the same as another artist who comes from, say, another country or another historical background. I am Armenian and each year my family and culture reflect on the events of the Armenian genocide which took place on 24th April 1915, but when you go into the wider world, you have to ask yourself: how can my mind be calm and stop firing these memories constantly? Revisiting and studying memory are my ways of keeping my brain and the trauma of certain memories under control.

DG: You state that ‘idea’ is the main decider of your work, rather than it being defined by a single media use. What do you mean by this?

TT: ‘Idea’ is a thought, something which needs to be translated and brought to life. It is a process of thinking, which is a system. An idea might be a sign and I might exchange that sign with you. Or, I might just have an idea and not attempt to communicate it to anyone else. But if an idea is formulated into a work, it becomes processed into some sort of product or result which has to then be understood. There is always a reason for the ways in which any idea is presented, and the manner in which one presents an idea should reinforce the idea itself. ‘Idea as idea as idea’ was a phrase that conceptual artist Joseph Kosuth often used when we were at a dinner or at his studio, in the course of a discussion. These conversations weren’t, however, the beginning of my attachment to the concept of ‘idea’.

In my work, the message is, to a large extent, constructed by the medium. In other words, the medium gives the message a form through which the idea can be expressed and experienced, It is, however, the idea which, to some degree, dictates the form. The medium and the idea combine to generate an experience. This experience is then handed over to the audience, and the audience’s experience of the work, completes the work. Again, each gesture or element in a creative work, including its medium, has to have a reason behind it, and the ‘idea’ should provide the central reasoning behind the work, so ‘idea’ is at the centre of the creative process, as opposed to leaning on one medium over another.

DG: You also state that you are developing a ‘new language’ across the fields of narrative, anthropology, futurism, trans-humanism, and cultural history. How do you view ‘language’ as a concept?

TT: A language is a method, a system of signification, or a set of formulas that we ‘agree’ on as representing a thought, an emotion, a fact, a meaning etc. When our mind is processing any data, it uses a certain system. These systems of signification and a computer are built similarly – based on 0’s and 1’s and an additional layer of energy, for example, electricity. When we process speech and articulate sound, we are expressing a way of thinking, similar to a meta-code. This arrangement of words and perception, combined with the noise, the memory interferences, and all the distortion and correction the brain makes or fails to make, are the causes and makers of a language. This applies to colour, sound, visual, or any other language. This idea can be read in Picasso and the Allure of Language, a book by Susan Greenberg Fisher. We are like vessels, with an input and output. Linking back to ‘idea’, we try to question where ideas come from, sometimes we don’t know but later on we may become more aware and then try to channel and structure them. As one grows, the more one is able to make use of that language, and the better you will be able to form it.

DG: Trans-humanism plays an important role in your work – how do you personally define this term?

TT: Trans-humanism is rooted deeply in my past, in my upbringing, although I did not recognise it by this term at the time, as the term had not been coined yet. As I mentioned at the beginning of our conversation, my father was a cardiologist and scientist. His research and thinking methodology were very strongly trans-humanist. He also believed there to be strong links between the brain and the heart and placed emphasis on the importance of emotional and mental wellbeing for the good health of a human being. He had his own ways of defining and dealing with death – often the most recent or current definition of ’death’. He always pushed beyond existing beliefs and, as a scientist, he experimented his own findings and logic in his work with patients. The most common phrase I remember him using was, ‘I was fighting with death’, and this is the essence of trans-humanism as we know it! Not accepting the ‘matter-of-fact’ little deaths of the heart, the feelings or life in things or people we love or hold dear in life, to certain memories, but trying to revive them or to reverse time, age, or other elements. These are minor but important, defiant acts of transhumanism.

DG: Another interesting statement you have made about your creative process is that it is based on a ‘quantum time-lapse’. Could you tell us more about this?

TT: I have always felt that I exist in different times and time-spaces – a quantum time-lapse, perhaps. This was a difficult realisation, but I have come to see it as an advantage as it helps me to pursue the happiness which I seek. I feel it is a way to see parallel universes at the same time and be able to ‘time-travel’ – to visit or revisit a ‘head-space’ – so, I feel, these processes make alternative realities possible. This is the way I create art; by spending time in a different reality. The ability to revisit other ‘head-spaces’, helps me to form solutions and if I’m not able to be in that type of energy zone, I can’t make anything – I feel frozen. Quantum time-lapse is also strongly present in navigating time and the mundane to reach a higher transcendence in any important part of our life and therefore of art.

DG: ‘Personal narrative’ also feeds into your work – what life stories are you inspired by yourself?

TT: My greatest inspirations are love and those people, animals, or things, with whom or with which I feel love. It might be my dog and my love for animals, or it might be another human being. I have also been inspired by certain personal stories and experiences, or by extraordinary people who have truly touched me, but some are too private to talk about.

I can, however, describe one important experience – the moment I looked at my dog Choco, when I had just got her to London on that first night. I remember looking at her and I couldn’t stop crying. I felt such an immense love, a powerful sense of empathy, and a desire to protect her deep fragility – a sense that her little life was in my hands, and the hands of my then partner. But, ultimately, I felt a very strong bond, as if I were her mother – after all, she was defenceless and motherless. This changed me completely. It shifted the way I feel the world around me and within me. We became the extension of each other – real soul-mates.

DG: The topic of ‘personal narrative’ leads us into one of your previous projects Pavilions of Memory (2018). You describe the project as an ‘interactive multi-media installation made up of sculpture, paintings, monitor and computers, webcam, sound-system, film installation and suspended perspex sculptures.’ Could you please tell us more about this project?

TT: Pavilions of Memory is the living proof that I was born, then I died and was born again. It is an emotional trans-human proof – not a scientific proof, but a primitive one. It represents a quest to share what is inexplicable, holding up a psychological mirror to the ‘other’, even when that ‘other’ is yourself. This might represent editions of you, reflections of you through your memories, or yourself in different times, all in the form of shifting narratives, just like memories. In this project, the digital code is written so that the viewer is superimposed onto the film, so that you become a part of it. You are able to visit a past place and hopefully make a positive change.

For example, there are tragic moments in history and in people’s individual lives that they might wish to go back and change, or erase completely. Memory is a fundamental component of trauma, and it is also central to the work itself. Years before making this work, I was in and out of suicidal tendencies, as I felt as though I couldn’t struggle through the pain anymore and Pavilions of Memory is a good example of that, because it’s saying that after so many disasters, after centuries of seeing what humans have done to themselves and each other, there is still hope.

DG: Thank you for sharing the personal experiences which shaped this project. What also interests me about Pavilions of Memory is one of the questions it poses: ‘How can we somehow melt the memory of the artist and the audience during the viewing of the installation?’ Did you find an answer to that question?

TT: No, I didn’t. Why? Because finding an answer to such a complex question is way beyond my capacity – that would take a huge team of people. But the idea came from two things: from constantly being haunted by suicide, and from my asking myself how I might be able to immortalise something. I didn’t want to be the creator of an artwork that hangs on the wall this time. I thought, can I go further and invite them into my brain? At least, for when I am no longer present.

The absence of the artist also plays with the idea of the work and the memory being separate from the person. This is important because, if you’re working on healing from trauma, the first thing a psychotherapist will tell you is that your problems are not you. The more you unpack your problems, the better you feel, because you are not as burdened anymore, which brings hope. With this installation, try to give this hope to others. To try and demonstrate how you might be able to put your brain in installation form, watch it like a movie, and try to change it. To deal with your problems from the outside – of course not literally, but it could be possible.

For example, there are laboratories, such as those at the Brain Mind Institute, École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, which are documenting, sectioning, and remodelling the human brain, and studying neuroplasticity. Professor Beatrice De Gelder, who leads the Brain and Emotion Laboratory, Maastricht University, says that the brain is not like a black box – it's creating connections all the time, and you with it. It is possible to document memories and then work with that data. These studies provide some of the starting points for my own projects.

DG: One of your artworks in the networks project, Textured Merged Networks Artifact 1, is a large-scale kinetic sculpture. The neurology of kinetic art has been of interest to researchers within the field of neuroaesthetics for decades, especially the effect dominance motion has on our senses when co-existing with other properties of an art piece e.g. colour and shape (Zeki & Lamb, 1994). What inspired you to make this artwork kinetic? What responses do kinetic installations draw from your audiences that may be different from non-kinetic installations?’

TT: There were two reasons. The main reason was that static art wasn’t enough to express what I felt, what I wanted to show. I needed other elements and ways of communicating thoughts, narratives, or feelings, or even acting like a scientist in a lab, setting up an experiment and monitoring the results. I always imagined a medium that was changing constantly, whether a movie, film, or another mechanical or computer based task or video art. I tried to use time as a medium, delay or repetition etc., which is possible with new media. The idea moves from the real to the digital and then the digital goes back to the real. The main point is the relationship or the exchange between input and output and online and offline. That was exactly what it was, because at the time I was moving between the two. When using any software or computer programs, things usually work themselves out. As an artist, I only have partial control over what's coming up. The only control I have are the decisions about whether to keep something, or not.

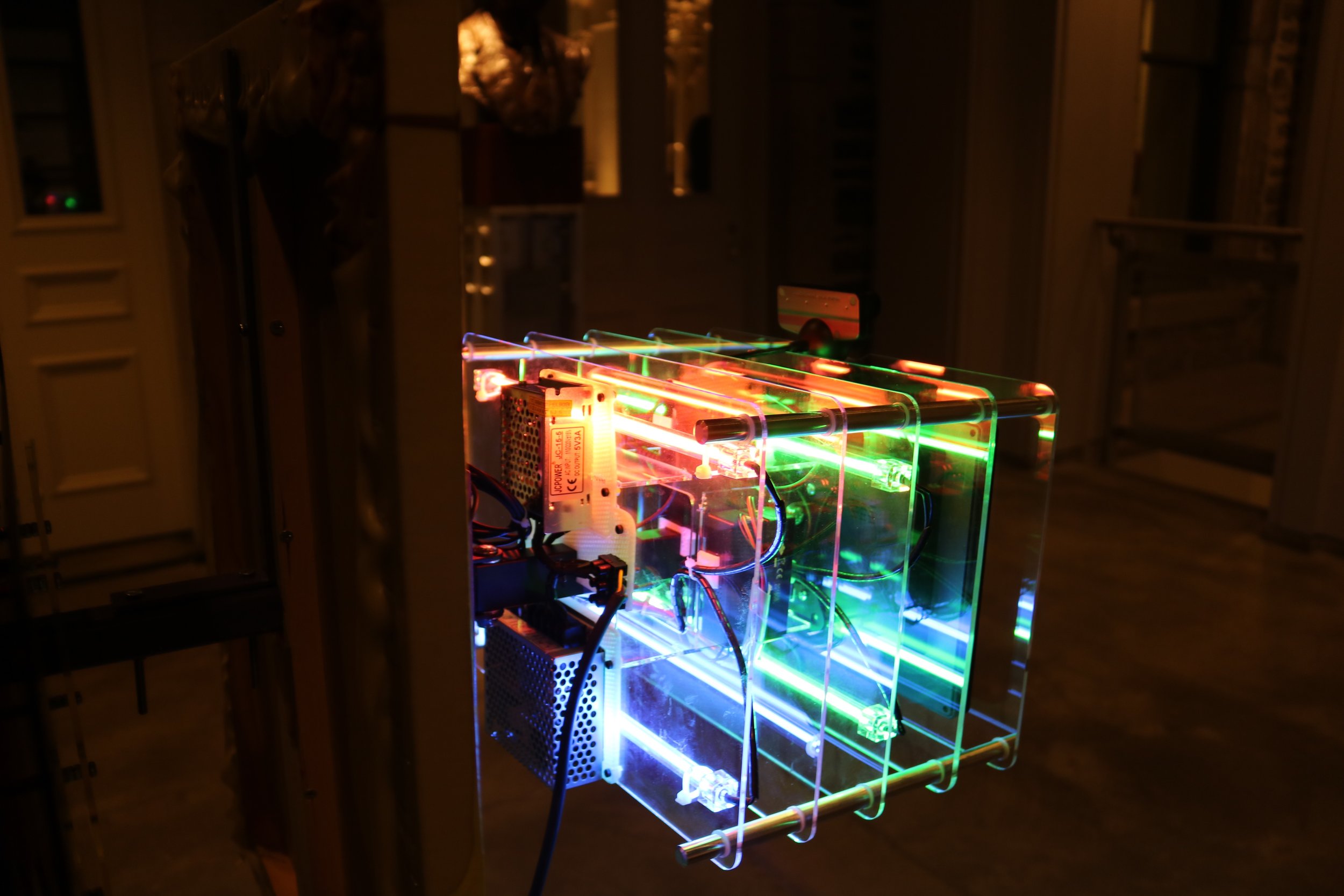

Video of Textured Merged Networks, 2016. Video credit: Studio Taline Temizian.

I also thought a kinetic art work would be fun and interesting for the audience. I was fed up with painting as a medium, because the chemicals had begun to bother me. Making this switch also meant I had to give away my control because I didn't personally put those pieces together, an engineer built them for me, but I still had to take responsibility for the outcome. On the other hand, it is always nice to see the concept and the idea suddenly taking shape and also be able to experience the concept from the point of view of another person, This was very important to me. It was important for me to see how someone else might interpret the work, and to see whether or not I would agree with the interpretation?

The installation has two facets: one kinetic and one static. The kinetic side is structured with coloured layers of Perspex, mounted on to the aluminium base of the sculpture. It includes motors, cogs, chain, rubber, and is connected to an electricity plug. This piece represents one merged scenario from the Networks Project as its first iterations, made in 2015. Every movement of the colour and noise panels affects the colour interactions created on the reverse side of the artwork, making variable possibilities something we experiment as we watch this piece.This piece was showcased at SKETCH London in a site specific installation in the context of a solo show, Saatchi Gallery in London and Art and Only Art platform.

DG: It is interesting to hear how the change to kinetic art affected your process. You have kindly shared some of your unpublished works with us, so the next set of questions will focus on these. In Imaginative Memory Backdrops (2018), the project brief begins with the quote: ’Memories are tarnished, distorted, transformed, refreshed, or recycled by our environment and its influence. Every time we introduce a new “value” into reality, you realise that you cannot ask for anything but reform’. How do you explore this idea in the project?

TT: My work is about memory, whether past, present, or future. The ‘one time’, all together, if you will. That is the ‘unpredictable future’ according to Derrida. There is a future which is predictable, programmed, scheduled, and foreseeable. But there is a future, ‘l'avenir’ (to come), which refers to someone who comes, but whose arrival is totally unexpected. For me, that is the real future – that which is totally unpredictable. I am interested in ‘l’avenir’. A creative work should make you feel a certain shiver or a pulse of happiness, a certain poetic dynamism. It is almost unimportant how you achieve that. It can be a sound, an image, ambiguity or intense clarity, a high-resolution screen, or simply the order of things.

The essence of an experience is like electricity – we don’t see it, but it is definitely there. In this yet-to-be-produced installation, the past-present is the centre point. It calls to mind works such as Homemade, 1966 by Trisha Brown, which refers to the significance of the time-brain connection and the impact it has on our emotions. In Brown’s 1996 performance of this work, timing is a crucial element.

Imaginative Memory Backdrops is one of my favourite projects, and I hope to release it in the near future. The project focuses on visual memory and the ways in which it functions. If we have a visual memory of a cinema screen and it shows a recording of us walking across the screen, in our memory, the image on the screen will never be the same. Gradually, the experiences and data that form our memories or the film on screen, fade or are covered with different substances and overlaps, which inevitably changes the visual landscape from that of our original ‘view’.

In this project, I film the passers-by who walk in front of the screen or across a room or some other confined space and this particular action leaves a shadow mark on the original image, which is then re-projected onto the screen. As this process progresses, screen is gradually covered by black spots. Then, when there is a certain level of distortion on the cinema screen, the code is designed to re-write the film and return to the original visual landscape. This is similar to the way we process things in life. Sometimes we might even try to start from ‘a clean slate’, and occasionally it works. But, as Derrida says, ‘A memory always survives us …’

DG: The project brief also states that the ‘installation tunes the viewers into an unpredictable perceptual experience’. Why is unpredictability key to this installation?

TT: Unpredictability comes from being in a situation you don’t have control over. The more people involved in an experience, the greater the unpredictability. Using a live, rather than a pre-recorded film, allows even less control and this adds another layer of unpredictability.

In this project, you don't know how your presence in front of the camera is going to be translated into an image or shadow, if you are going to be alone in front of the camera, or when the film is going to be rewritten. What are the sensors are telling the environment? Who else is influencing them? If you encounter someone else in the space, you might look at them and fall in love, or you might think, ‘I want to run out of this space, I feel bad energy’. It's just a matter of how many different outside elements you encounter. For some people, it might feel similar to looking into a mirror for the first time, as one does as a child, and not understanding that the image you see is not really you. You're becoming a part of multiple layers. It’s a very delicate thing, especially to experience in public.

When you are in an art environment, your senses are heightened, regardless of whether you are a sensitive person or not. These interactions are magnified and unpredictable sensory experiences, and my team and I aim to create a scientifically advanced set up, with a new vision of how to generate responses from our audience and shift them. We also explore this same idea in my upcoming project, Past Tomorrows, and in our research partnership with iCity Brussels.

DG: Now I would like to move from unpredictability to empirical content. In one of your other unpublished works, The Game and the Acrobat (2022), you collect scientific data during and after the show itself, which can then be used for scientific studies. Firstly, what is this project about and, secondly, why is this data important for this project?

TT: The Game and The Acrobat (TGATA) is fundamentally a research project exploring a trans-humanist take on the question: how can our brains survive trauma and ongoing turbulence? The title and some of its philosophical baselines are inspired by Marcus Steinweg’s books, and by my artistic research into digital mediums, in particular digital performance. The ‘game’ represents the workings of the human psyche, our anxieties, and difficulties. It is a dynamic time-based theatrical installation, in which digital media plays a fundamental role.

The variables we encounter and have to manage on a daily basis, mean that our brains and emotions need to coordinate effectively. The experiments set up in my work are based on the daily challenges we need to overcome – to learn, relearn, or forget, in order to be able to handle life. In order to understand the parameters of a situation, we need to determine baselines, and data collection is crucial requirement when investigating a given statement. TGATA investigates the study of trauma and trauma survivors, who frequently live in a state of alert. This state of alert can be ameliorated and art might be able to show other scenarios wherein peace and hope for happiness seem possible. This idea also formed the central thesis of my thirteen-year work, The Networks Project (2009).

Another work which was influential to our creation of TGATA, was Visions of the Now (2013), a book published by the Stockholm Festival For Art And Technology. But the most influential starting point for this project was the 1966 future envisioned in Sagan om den Stora Datamaskinen, (The Tale of the Big Computer), written by the physicist Hannes Alfvén. I read this reconstructed version in 2017, after finding it in Berlin. It was like a book, a fold with other booklets and papers inside, which held the beta research from a project which took the form of a conference which had been organised by artist Anna Lundh. The conference had shown experiments and digital performances. All of these influences, research projects, and their data contributed to the technical structure and planning of TGATA. So, in this project, like most of my recent and upcoming works, data plays a very important role. It helps us to discover the rules of interactions, what state of mind your audience or subjects are in, and whether or not the space and rules of the performance are having an affect on them?

One of the key questions becomes: if we have scientific experiments on the spot, if there are things which are not so complicated and do not require a lot of heavy lab equipment, can we actually locate and measure people's generated memory patterns. I was trying to find explanations for the occurrence of PTSD and to determine how we might be able to shift it. I'm not a scientist, but I was wondering if it would be possible to create that shift through performance, digital response, and communication, because those things do affect us.

DG: I’d like to now zoom in on the topic of emotions. In the trailer for another of your unpublished works, PAST TOMORROWS, the project is described as an ‘emotion lab’. What is an emotion lab?

TT: The term ‘emotion lab’ comes from Professor Beatrice De Gelder’s studies and books. Her study of emotions and the body, and in-depth research into perception and distortion in both healthy and unhealthy subjects, lead me to try to see how (without any neural networks, medical chips, or other types of invasive interventions) I could gather information about an audience at any given time and try to shift their state of mind.

I began this project in 2017 and the team comprises an experience designer, a coder, and data experts, with other collaborators to be confirmed shortly. Together, we are in the process of creating a time-based installation, representing an artificial ecology, drawing on the cybernetic systems of Gregory Bateson, as described by coder, composer, and computer scientist, Nick Rothwell. The project will involve a modelled system of data, algorithms, and emergent behaviour, and it relies on scientific advancements in neuroscience, artificial intelligence, data science, and cardiology, in an attempt to catalyse the connection between emotions and the brain. The question we ask is: does trauma reside in the brain, the heart, or both?

Data and digital twins are both very important elements to this project, because both recorded primary and secondary scientific research are crucial to understanding subjects, audiences, and their mental and emotional states. This type of insight and understanding are crucial to the changes I love to achieve as an artist through science.

DG: Over the course of this conversation, we have touched on the theme of trauma, and here we will explore the theme in more detail. Your work has been heavily inspired by the states of mind caused by trauma. As an artist, what do your installations offer the audience on this theme? What does your art bring to public awareness of traumatic states of mind?

TT: Trauma is changeable, like the brain. It is never hopeless. It isn’t easy to work with and transform generational trauma, because it is encoded at DNA level, but DNA can also change. Additionally, trauma can be held in an individual’s memory. As memory is partly formed through experience, experience is key to forming and reforming any memory. If we focus on the internal processes of forming an image or memory, then we might have better ‘control’ over the outcome, or output, if you will. and manipulation or erasure of the same image or memory.

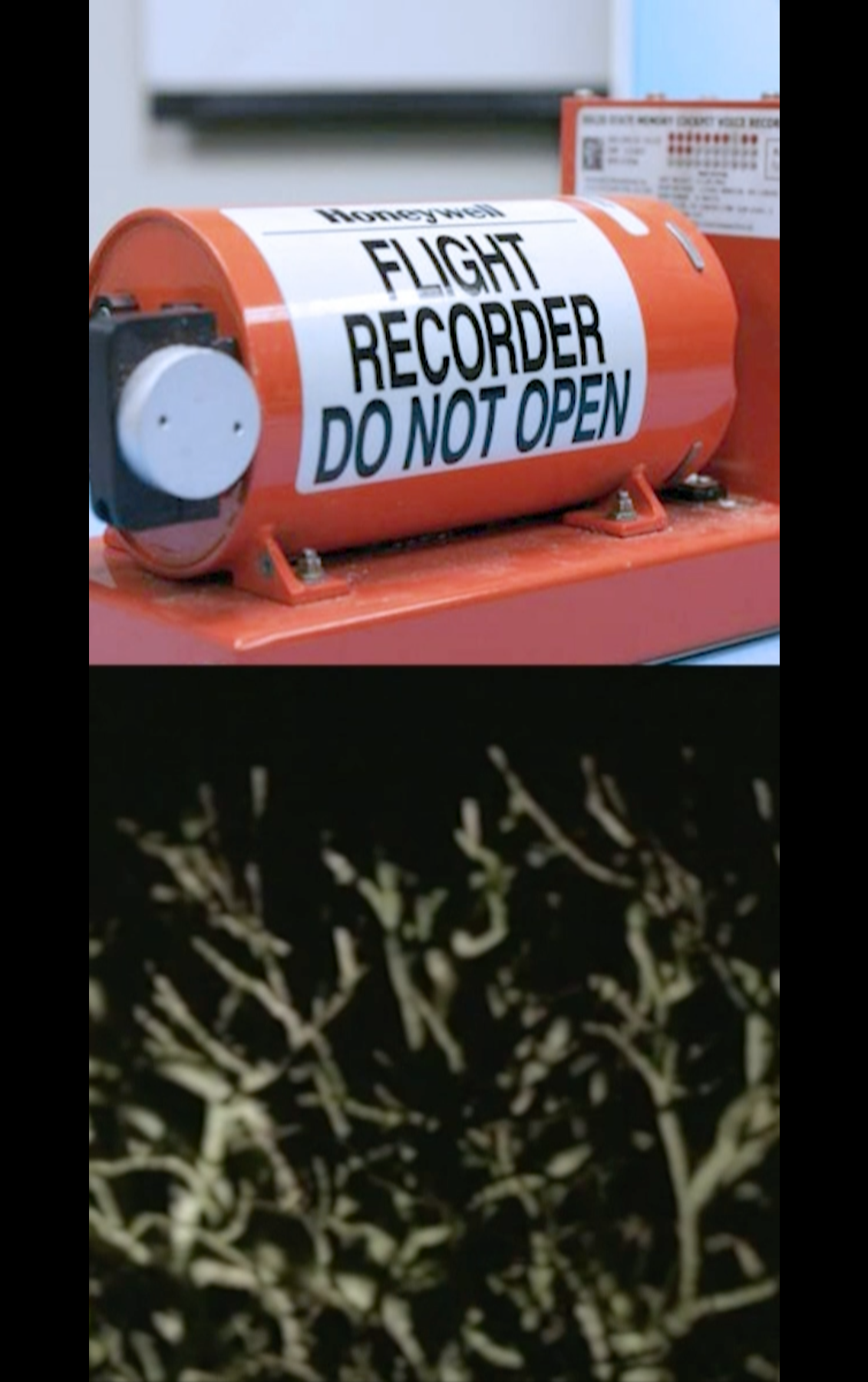

One of my works, Project WOW, focuses on this process. It follows the idea of ‘revisiting the crash scene’ and is based on studies which suggest that revisiting the scene of a traumatic experience could be beneficial for those suffering from PTSD. Project WOW started in 2017 with The Brain Project research. It explores the interplay between trauma and memory, in a comparative study between neuroscience and avionics. ‘WOW’ stands for ‘weight off wheels, weight on wheels’ – an aviation term used to describe blackbox activity. When the wheels of the aircraft are off the ground, recording begins, and when wheels are on the ground, recording stops – unless there is a crash.

This project was partly exhibited on a very large video screen on the Hybrid Tower in Mestre, Venice, for this year’s opening of the Venice Biennale. I was invited to take part by Hyperfutures and did so in collaboration with wildlife filmmaker, Oliver Page. With this project, I am aiming to sensitise people, so that they feel trauma in a more lucid way, in order to eventually help them heal. This concept carries on into other projects, such as Concomitant Variants and other upcoming projects which are AI-based.

My recent solo show in Dusseldorf was the main ground for revisiting my experimental performance projects, especially the collaboration I was privileged to do with German composer and musician, Sven Helbig. This work utilised digital and electronic material in its production, and an AI-created film that experimented with a whole new medium, and which was made in collaboration with experience artist, Max Seeger. We incorporated electronic sound, contemporary experimental ballet, poetry, and a live electronic concert. This project also forms the foundation for other new material I am working on.

DG: After our in-depth discussion of trauma, I would like to end this conversation on another important theme in your work: hope. What hope do you intend to leave your audiences with? At what point in the installation do you experience it and how long do you intend it to last?

TT: At the beginning of my own journey of healing, moments of ‘hope’ used to last milli-seconds, often a phantom of a milli-second, but I was able to gradually extend these moments to last seconds, minutes, and even hours. It is possible to build emotional stamina by training the brain like a muscle, but it is a very long and painful process. For me, it then became a system, then a formula that generated itself, and, eventually, it became a way of seeing the world. This process and experience had an important influence on the art I create and they also presented a parallel challenge – acclimatisation to a newly gained sense of happiness.

I have learnt that my present actions and preparedness for certain experiences are both changeable, and that noticeable changes in my level of preparedness can occur with just a single variable. There is a possibility that when you present this idea to the viewer, you give them hope. I’m not saying that if you experience the installation, suddenly everything difficult and traumatic disappears. It’s not as simple as that. It's not about everything being perfect, because everything is not going to be perfect, but it is about how we learn to live with difficult experiences and how we can reformulate our experiences to cope with them more easily. If I know my triggers and what affects me, then I am more able to understand and reformulate my own difficulties, or at least work around them. So, that is the hope that I'm trying to give to the audience.

DG: Thank you for taking the time to speak with us, Taline.

For more information on Taline Temizian and her work, please visit her website here.

All images and videos shown courtesy of the artist ©️ Taline Temizian. All rights reserved.

References

Bohacek, J., Gapp, K., Saab, B.J., Mansuy, I.M., ‘Transgenerational Epigenetic Effects on Brain Functions’, 2012, Epigenetics and Heritability, Biological Psychiatry Journal, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.08.019

Dooley, M. and Kavanagh, L., 2014. The philosophy of Derrida. Routledge.

Exhibit A: Sagan om den Stora Datamaskinen.

The Tale of the Big Computer / (Ut)Sagan om den stora Datan, 2017, MIT Press

Lundh, Anna, Visions Of The Now, 2013, Sternberg Press

Murray, Hannah & Merritt, Christopher & Grey, Nick. (2015). Returning to the scene of the trauma in PTSD treatment - Why, how and when?. The Cognitive Behaviour Therapist. 8. 10.1017/S1754470X15000677.

Steinweg, Marcus, Inconsistencies, 2017, MIT Press

Wang TT, Mo L, Shu SY. [The brain mechanism of memory encoding and retrieval: a review on the fMRI studies]. Sheng Li Xue Bao. 2009 Oct 25;61(5):395-403. Chinese. PMID: 19847359.

Zeki, S., & Lamb, M. (1994). ‘The neurology of kinetic art’, Brain, 117 (3), 607-636.