TAKIS AT WHITE CUBE: MAGNETIC ATTRACTIONS

The French writer Alain Jouffray reports that, one evening in April 1959, he bumped into Takis on the pavement of the Rue de la Hauchette … ‘It’s happened’, said Takis, ‘I’ve got it!’ It sounded exactly like Archimedes’ ‘Eureka’ … And he showed me the first telemagneticsculpture (it was I who coined the name the day after), in which metallic elements are held in suspense in the air by a magnet … Takis’s joy and enthusiasm was ineffable, he was almost weeping.’ Takis was the nickname of Panayiotis Vassilakis (1925-2019), who was born in Athens but spent most of 1954-86 in Paris (with spells in London and America), before returning to his native Greece in 1986. He was the first to bring what looked like science experiments into art – a shocking move the early 60’s – and continued over the following sixty years to take a particular interest in how magnetism could reconfigure sculpture by freeing it from its usual subservience to gravity, and make us aware of forces we cannot see. The first substantial European exhibition of Takis’s work since his death at 93 took place at London’s White Cube gallery in June 2021. I spoke to Toby Kamps, the show’s curator, to learn more.

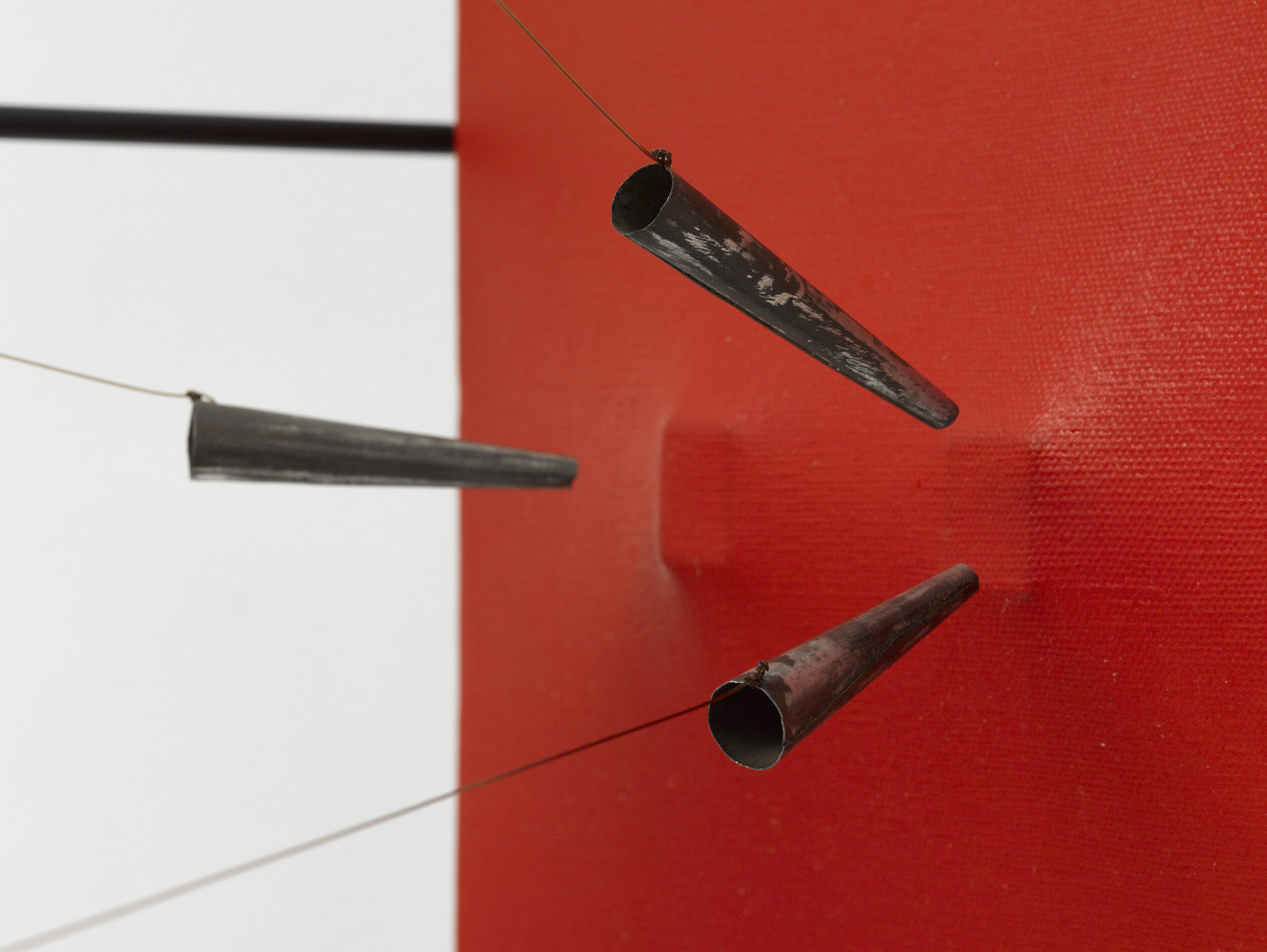

According to Takis, magnetism binds – together in space – objects, metals and roaming particles of the cosmos. Using the prefix ‘tēle’ from the Greek meaning ‘at a distance’ he followed Jouffray in categorising his series of works as ‘Télé-peintures’, ‘Télé-sculptures’ and ‘Télé-lumières’. The ‘Télé-peintures’ demonstrate the effect at its simplest. They might be compared with Fontana’s iconic ‘Cuts’ (1958-69) in which he slashed through the canvas to reveal the void behind it, so complicating how we read the painting’s ground. Takis uses thin wires attached to the ceiling to restrain conical metal shapes in front of canvases, effectively extending the ground of the painting in the opposite direction, towards the viewer.

There’s nothing special about the materials. Takis, who grew up during World War II and fought for a leftist group in the Civil War (1943-49) which followed on from the German occupation of Greece, had an ongoing predilection for turning ‘swords into ploughshares’. His early sculptures were all built from found elements, often from the military surplus which made up much of the electrical and mechanical stock sold from a run of shops near London’s Tottenham Court Road. Having sourced suitable magnets, it was intuition and experiment, rather than mathematical calculation of forces, which led to Takis’ configurations, and the same is true when installing the works today. Although the dimensions of the rooms receiving them need to be taken into account, Kamps says ‘it’s fairly simple if the technicians know what they’re doing. They pull the pre-stretched wires, and crimp them just when it’s working - you get a ballpark idea of the length, then it’s a matter of tightening it’. Kamps mentions that magnets are actually quite common in museums as unobtrusively small silver ones can now be powerful enough to hang substantial paintings – which ‘can be a problem, as kids will swallow them as if they’re sweets, and if two stick together inside them it is highly dangerous’.

Once a work such as Mur Magnétique (1970) is in place, our attention is called to the forces which we sense must operate in the gaps between the canvas and the hovering metal elements. The invisible becomes perceptible. For Takis that was emblematic of art’s power, but it can stand in more broadly for the metaphysical idea – resonating equally with Plato, religious belief and modern physics – that what we can perceive is only part of the world’s story. Takis also held that magnetism and attraction between people were one and the same thing, but the equation wasn’t made explicit in his work until he developed the ‘Erotics’ in the 1970s-80’s. Those put magnets inside casts from the bodies of models – who included his gardener – so that, for example, in Saint Sebastien (1974) they attract arrow-like forms which parallel a prominent erection, while in Magnetic Erotic (2003), a female torso has magnets inside which draw nails into emphasising the breasts. According to Takis ‘if it is sensual, the sensation is in the transmission. It is always magnetism’. He evidently knew something of human attraction: the artist Liliane Ljin, his wife from 1960-67, reports that he was ‘very romantic’ and that ‘when I met him, he was listening to the stars. He said he heard their music and was working on an instrument, which would trap it so that all could hear the sound.’

The ‘Télé-peintures’ are static, but the ‘Télé-sculptures’ are often kinetic. Magnetic Sphere (1966) has a piece of iron in the middle of a foam sphere, so that when electromagnets are turned on and off, the foam is alternately captured and frozen by the electro-magnet or bounced off by it. The timing is random, but makes for a beautiful shuddering dance which Kamps calls a ‘ballet electromagnétique’. The movements might suggest mental activity, as in Magnetic Brain (1975). A more political predecessor was the performance The Impossible: A Man in Space (1960). At the time of the space race and the height of the Cold War, the South African poet Sinclair Beiles was suspended in mid-air through a system of magnets while he recited Takis’s anti-nuclear ‘Magnetic Manifesto’: ‘I am a sculpture … There are more sculptures like me. The main difference is that they cannot talk... when they try to speak, they explode … I would like to see all nuclear bombs on Earth turned into sculptures …’

Takis was an autodidact in all respects – theoretical science and philosophy as well as art and practical electronics. That fitted with his even-handedness in concluding that ‘artists and scientists are very similar. If you engage in questioning you are a researcher … A painter does research about colour, how to apply it, what kind of colours to use, what chemical reactions they will have. I have this combination in my work as well. I work mostly on magnetism.’ He was very much inspired by the thinkers of ancient Greece, and this is particularly evident in the ‘Musicals’, which make sound – another invisible force – a principal feature of kinetic work. Pythagoras saw the whole of heaven as enacting the ‘music of the spheres’, and following on from him, astronomers and mathematicians used the term as a way to model how the planets and stars interact; while artists and musicians imagined the sounds implied. Takis saw a connection to his use of magnetic fields. ‘If only’, he wrote in 1974 ‘with an instrument like radar I could capture the music of the beyond … If this object could capture and transmit sounds as it turned, my imagination would be victorious’. He had this in mind when he created the first Musicals in 1965: in these audio-kinetic sculptures, an electromagnet causes a needle to bounce against a stretched and amplified wire in what Guy Brett calls ‘a shivering, trembling motion, caught between gravity and the magnetic pull’. That sets off a closed system of sound production, picked up by a tiny microphone attached to the piano wire, then sent through sound filters to a loudspeaker. As Takis said ‘My role in the acoustic end of the product lies essentially in the choice of string, its length and the degree of magnetic force used to strike the string. Once you set the instrument in motion, the instrument itself becomes its own agent, and acts of its own accord. This is therefore a ‘virtual’ music composition.’ Wind forward two decades, and the NASA website reveals that the typical outputs of this methodology were the sonic equivalent of universal electromagnetism, as picked up by Voyager spacecraft leaving the solar system. Takis had indeed hit upon the sound of the cosmos, and as Brett suggests, that is consistent with hearing that as ‘nearer to the reality of energy’ in line with ‘the ancient Indian tradition of OMMMMMM – the sound of the ‘all’, the entirety of the universe.’

Despite his lack of academic qualifications, scientists respected Takis – so much so that he was visiting researcher at MIT in Cambridge, Massachusetts from 1968-71. The gauss is the unit of measurement of magnetic induction, and Kamps tells of how astonished the scientists were by Takis’s ability to act as an accurate ‘human gauss meter’ by using his hand tomeasure the strength of magnetic field around electrical devices. Takis called himself ‘telekinetic’, and later in life he got very interested in bio-magnetism: the human brain puts out tiny amounts of electric vibration, and he reasoned that, as many animals have some sort of compass – e.g. bees have iron in their thorax – we must have some sort of in-built compasswith which we’ve lost touch. Takis also thought that, as he was sensitive to an unusually broad spectrum of the electromagnetic spectrum, he could channel what he received into healing practices.

Magnetism, then, was Takis’s principal scientific interest. He described it as ‘an infinite, invisible thing, that doesn’t belong to earth alone. It is cosmic; but it can be channelled … I would like to make visible this invisible, colourless, non-sensual, naked world which cannot irritate our eye, taste, or sex. Which is simply pure thought.’ As such, his artistic focus was, to adopt Duchamp’s term, not retinal but conceptual, his obsession being with the concept of energy. That may explain why the well-established 19th knowledge of magnetic fields and their interrelationship with electricity was of particular significance to Takis – it was a key step towards the revelations of quantum mechanics, the ultimate account of the invisible yet powerful forces underlying the world.

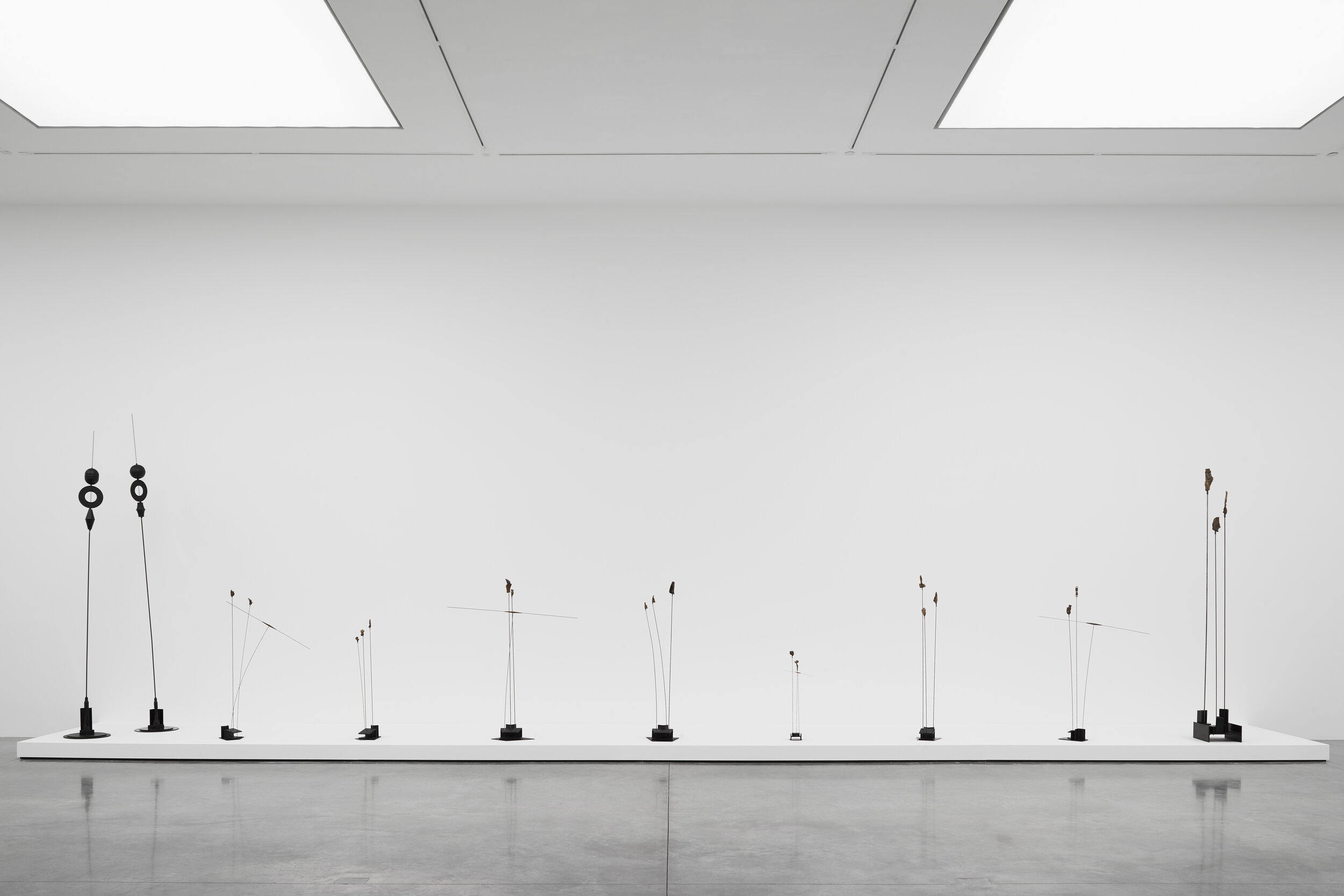

That said, Takis was interested in much more than magnetism. The ‘Signals’ series may be his best-known works: tall, slightly flexible metal poles with found objects placed at the top. He saw them as means of communication – and even told Kamps they could stay in touch that way when several were installed in Houston – but they are more poetic than scientific. And the key to the ‘Télé-lumières’ is light: not from bulbs, but from ‘Mercury Vapour Rectifiers’, which Kamps describes as ‘right out of Frankenstein’s laboratory’. They were used to switch between alternating and direct currents before the development of transistors in the 1960’s rendered them obsolescent. Takis liked how the gas built slowly to an aqua blue colour. It’s ‘like capturing a cloud in a jar’, says Kamps. The Tate exploited this in its 2019 retrospective by setting the Télé-lumières to switch on and off in 15-minute increments. Yet the rectifiers use magnets, as well as mercury and heat, to control the flow of electrons in an electric circuit, and Takis was, of course, aware that light is an electromagnetic wave.

Summarising Takis’s unique qualities, Kamps emphasises how ‘he brought in weird stuff which was alien to art, but let it speak for itself. He never sought to illustrate or symbolise the fourth dimension that, but incorporated it by making the invisible somehow palpable.’ Perhaps we should end as we began, with Alain Jouffroy: ‘Never, since Brancusi, has a sculptor penetrated the elemental so deeply. That is why I salute Takis as one of the great witnesses of the future world: the world in which all energy will have been captured.’

All images shown courtesy of © Takis Foundation and © White Cube