SEISMA IN BERLIN

There’s no shortage of art in Berlin, especially during the annual Gallery Weekend in May. So the chances are that you’ll find a few shows that bring science and art together interestingly: here are four such from Seisma’s recent visit, covering microbiology, scientific method, artificial intelligence and rare minerals.

KATHRIN LINKERSDORFF: ‘MICROVERSE’ AT HAUS AM KLEISTPARK

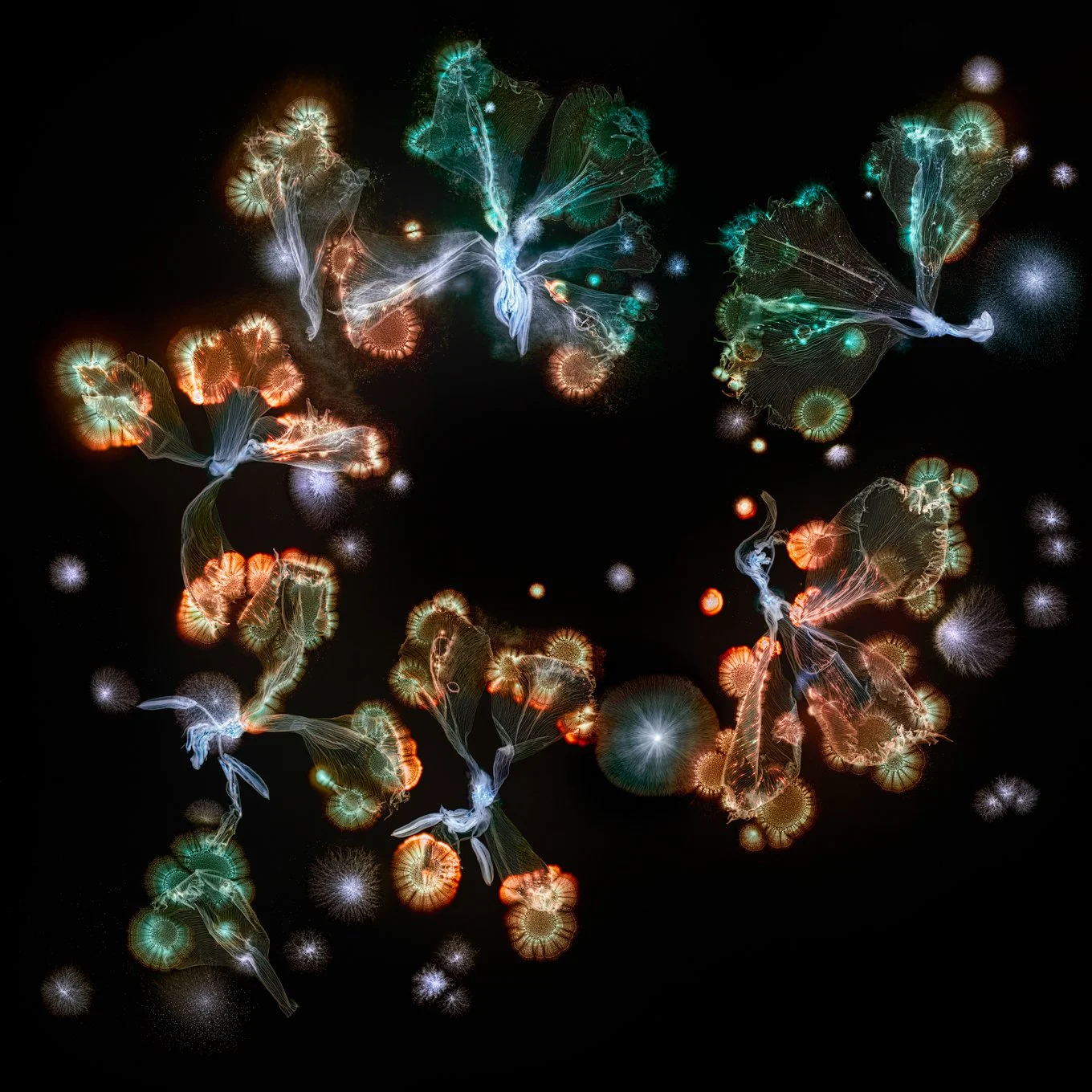

Berlin-born artist Kathrin Linkersdorff is known for intervening in flowers, then making monumental photographs of the results. The Haus am Kleistpark provided an excellent overview of four series: the Wabi Sabi, the Floriszenzen and the Fairies, as well as the recent Microverse itself. began her career as an architect working in Japan. There, she became acquainted with the aesthetic concept of Wabi Sabi, which holds that ephemerality and imperfection are integral and even beautiful parts of life. She sees her photographs as embodying that worldview, presenting images of organic life as it transitions to a state beyond.

Building on that acceptance and contemplation of the ephemerality of all things, the series Wabi Sabi (2013-18) takes true beauty as showing itself not in the moment of blossoming and opulence, but in that of withering and fading away. With that in mind, Linkersdorff’s series aims to photograph flowers just before the process of decay robs them of their natural grace: that exact moment in time is the point of these flower portraits.

Floriszenzen (2019) goes a further step with those withered and dried out flowers by re-exposing them to liquid. Rehydrating dried flowers causes their cells to swell and expand, changing their shape and structure so that the tulips photographed ‘come back to life’ in unusual contortions and with curious apparent gestures. At the same time, the plant’s pigments move from the flowers into the solution, leaving behind traces – the ‘fluorescences’ of the title - that Linkersdorff sees as alluding to the eternal in that which is transient.

For the Fairies, ongoing since 2020, Linkersdorff found a controlled way to extract the plant colour – the anthocyanins – from the dried tulips. That enabled her to make the transparent structure of the delicate fibres visible, yielding a new window of sorts onto the beauty of the petals, while accentuating their vulnerability. Later images from the Fairies series reintroduce the previously separated flower pigment into the compositions: it operates as a coloured ink, bringing about a reunion with the colour in new formations. As the show text puts it: ‘Tulip petals turn into brushes and open new dimensions of experience. Colour becomes a metaphor for aliveness.’

Linkersdorff’s latest series is Microverse, developed from 2023 onwards. As an artist in residence at the Institute for Biology / Microbiology at the Humboldt University in Berlin, she collaborated with microbiologist Professor Regine Hengge to examine the behaviour of streptomycetes in biochemical processes of decay. This type of bacteria, typically found in healthy soil, has a striking ability to produce its own antibiotics, which form vibrantly-coloured pigments. Linkersdorff placed the streptomycetes onto plants and flower petals that she had already discoloured, and various scenarios unfolded depending on the environment and preparation. In combining decay and new growth, Multiverse visualises the entire cycle of material flows in nature. The striking results suggest a trammelling between the microbiological and the celestial.

Taken as a whole, Linkersdorff goes beyond the most usual depictions of flowers – as living, picked, or pressed – to make still life of the laboratory rather than of the house or garden. That brings her to corresponding different aesthetics, just as Wabi Sabi arrives at a differently-motivated aesthetic to classical western traditions. In doing so, she also demonstrates that the boundary between living and dead is not the same as that between active and inactive.

For more information on Kathrin Linkersdorff and her work, please visit: https://www.kathrinlinkersdorff.com/

JIMMIE DURHAM: ‘ART AND SCIENCE ARE THE SAME THING’ AT BARBARA WIEN GALLERY

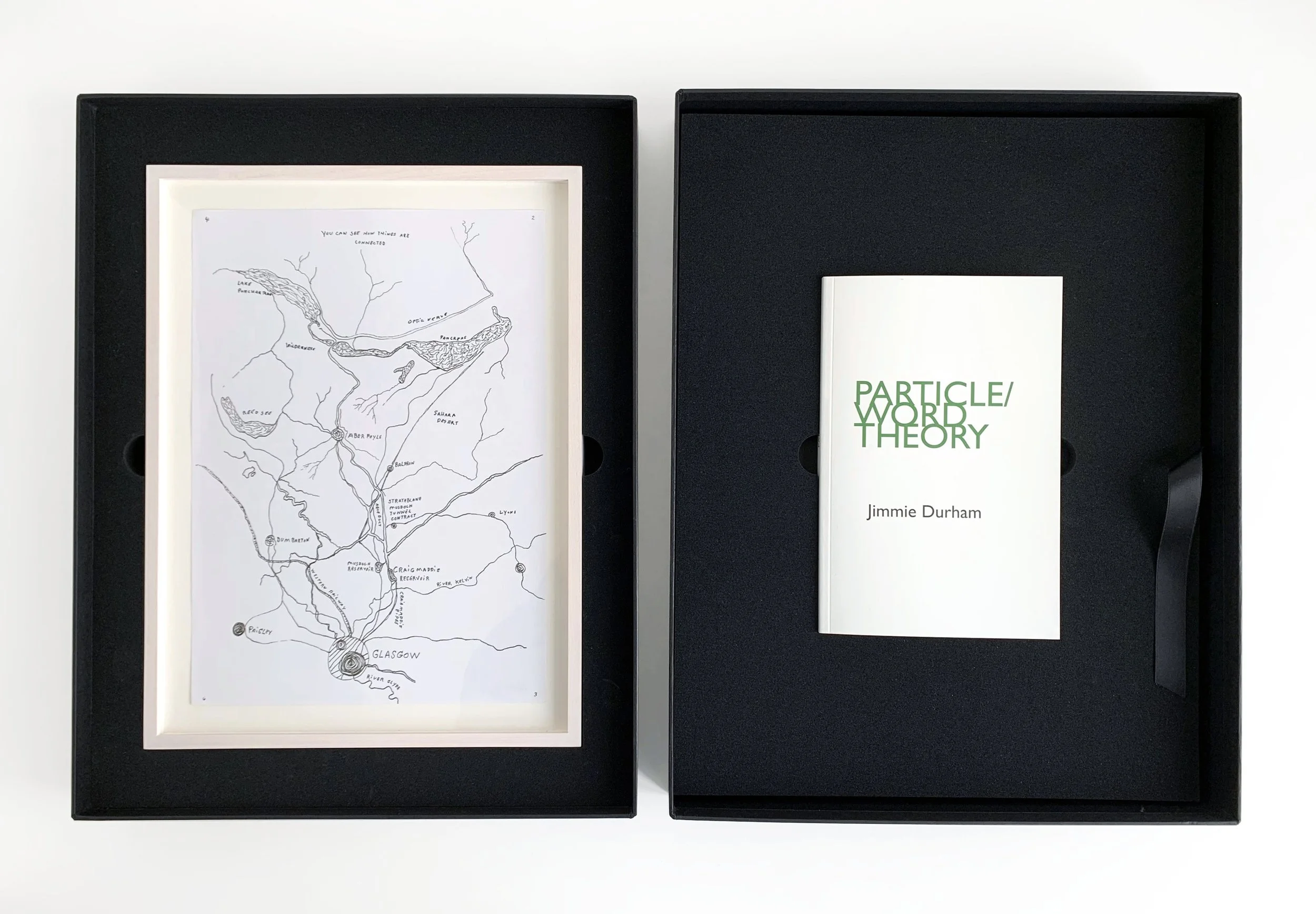

Jimmy Durham (1940-2021) is best known for sculptural work that combines found objects, natural materials, and text in order to question white Western prejudices in relation to Indigenous people. His range is wide, with drawings, photographs, videos and extensive writing, taking up such issues as the politics of representation, the legacy of America’s colonial history, and conceptions of authenticity, statehood and exile – and science. He regarded science as a human, not a European, thing, and took a strong - if unorthodox - interest in both its content and its methodologies. As he put it: ‘My work is based on the idea of science as curiousness, as a new way of seeing things, inquiry without preconception which leads to change and innovation. That is what science means to me: a lack of predefined ideas, an acceptance of discovery, an unexpected vision of reality.’ Hence his statement from which the show’s title is borrowed: ‘I often describe myself as a theoretical biologist … I like to think about biology and make up theories about biology. I do not have to know anything. I just have to think about things. I think there is not a division between art and science. Art and science are the same thing.’

Durham was based in Berlin from 1994 onwards, and Barbara Wien says that the idea for her exhibition arose while working with him on the book of poems, Particle / Word Theory, in which the world of science is ever present. One poem is dedicated the Austrian nuclear physicist Lise Meitner, another to the Brazilian mathematician Aturo Avila. Another poem uses quotes from scientific journals as found material: ‘The essays listed in the letters section of the table of contents of the September 2015 issue of Nature Materials magazine’ includes for example ‘Spatially resolved ultrafast magnetic dynamics / Initiated at a complex oxide heterointerface’, ‘in situ study of the initiation of hydrogen bubbles / At the aluminium metal oxide interface’ and ‘subnanometer ligand-shell asymmetry leads / To Janus-like nanoparticle membranes’.

The works in the show similarly place scientific concerns into new contexts. Heisenberg’s Principle, 1989, picks up on the discussions surrounding Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle and Schrödinger’s cat. Durham labels a black box with the text: ‘Werner Heisenberg explained his uncertainty principle by saying that if you have a kitten in a box it is neither alive nor dead. Until you open the box the kitten is only potentially alive or dead’. One might take the form as a reference to Robert Morris’s Box with the Sound of Its Own Making, 1961, the original paradoxical box in modern art; and the conceptual appropriation as an analogy for artistic production: until you put work before an audience, you can’t be sure whether it will come to life or not.

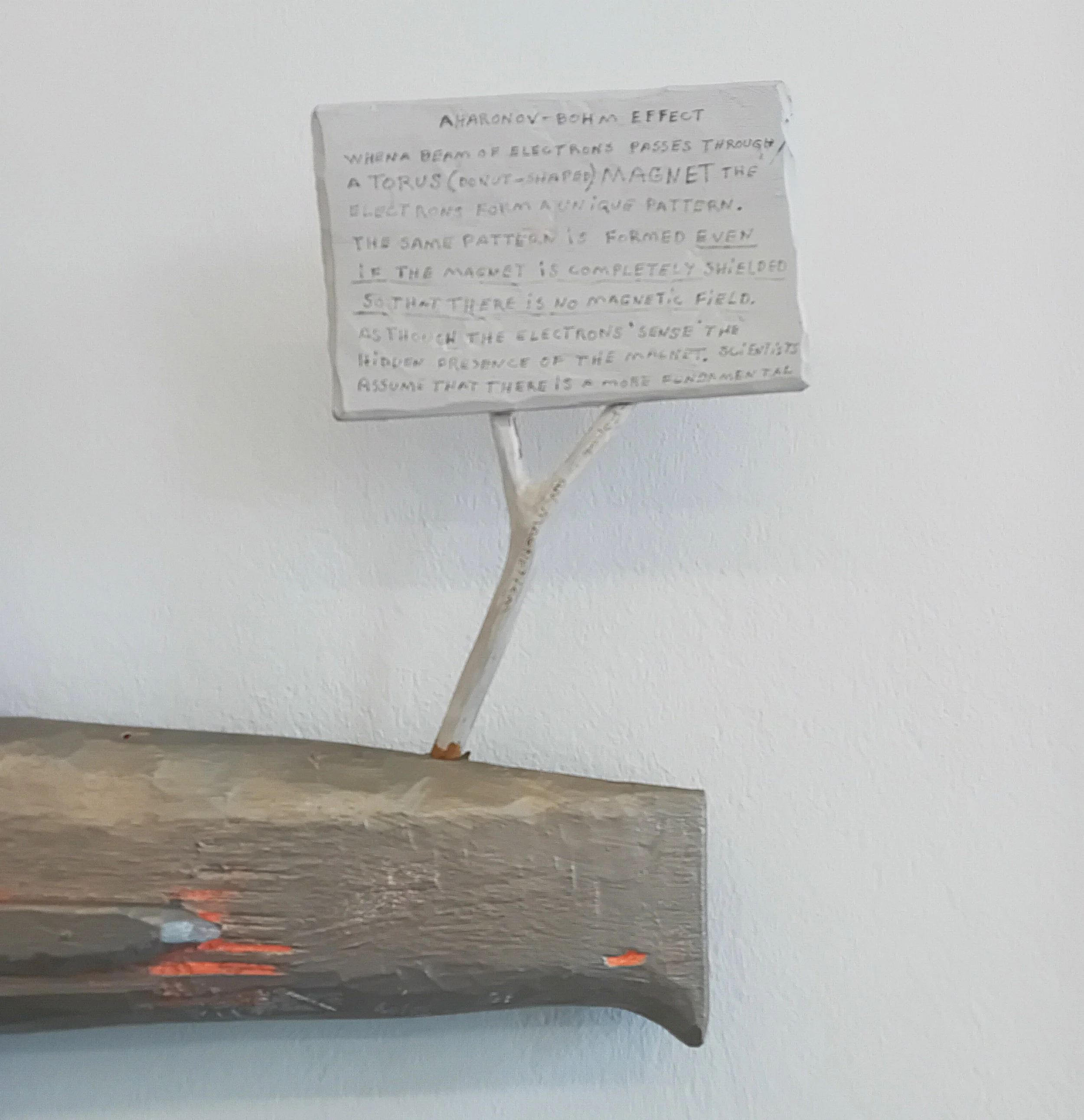

The wall sculpture The Aharonov-Bohm Effect, 1989, presents a less widely-known surprise from the quantum world. Durham visualises the phenomenon whereby charged particles are influenced by an electromagnetic field, even though they move exclusively through a region free of magnetic fields. On a text panel Durham explains that ‘when a beam of electrons passes through a torus (donut-shaped) magnet the electrons form a unique pattern’ and ‘the same pattern is formed even if the magnet is completely shielded so that there is no magnetic field’.

He speculates that it’s ‘as though the electrons ‘sense’ the hidden presence of the magnet. Scientists assume that there is a more fundamental force of magnetism.’ We might take that to be the influence of the gauge potentials of electrodynamics in nonrelativistic quantum mechanics. In contrast to classical mechanics, where the equations of motion contain only the electric and magnetic field, in quantum mechanics the Schrödinger equation explicitly contains the electromagnetic potentials, as set out by Aharonov and Bohm in 1959. Here, too, one might speculate on parallels with the ineffable in art.

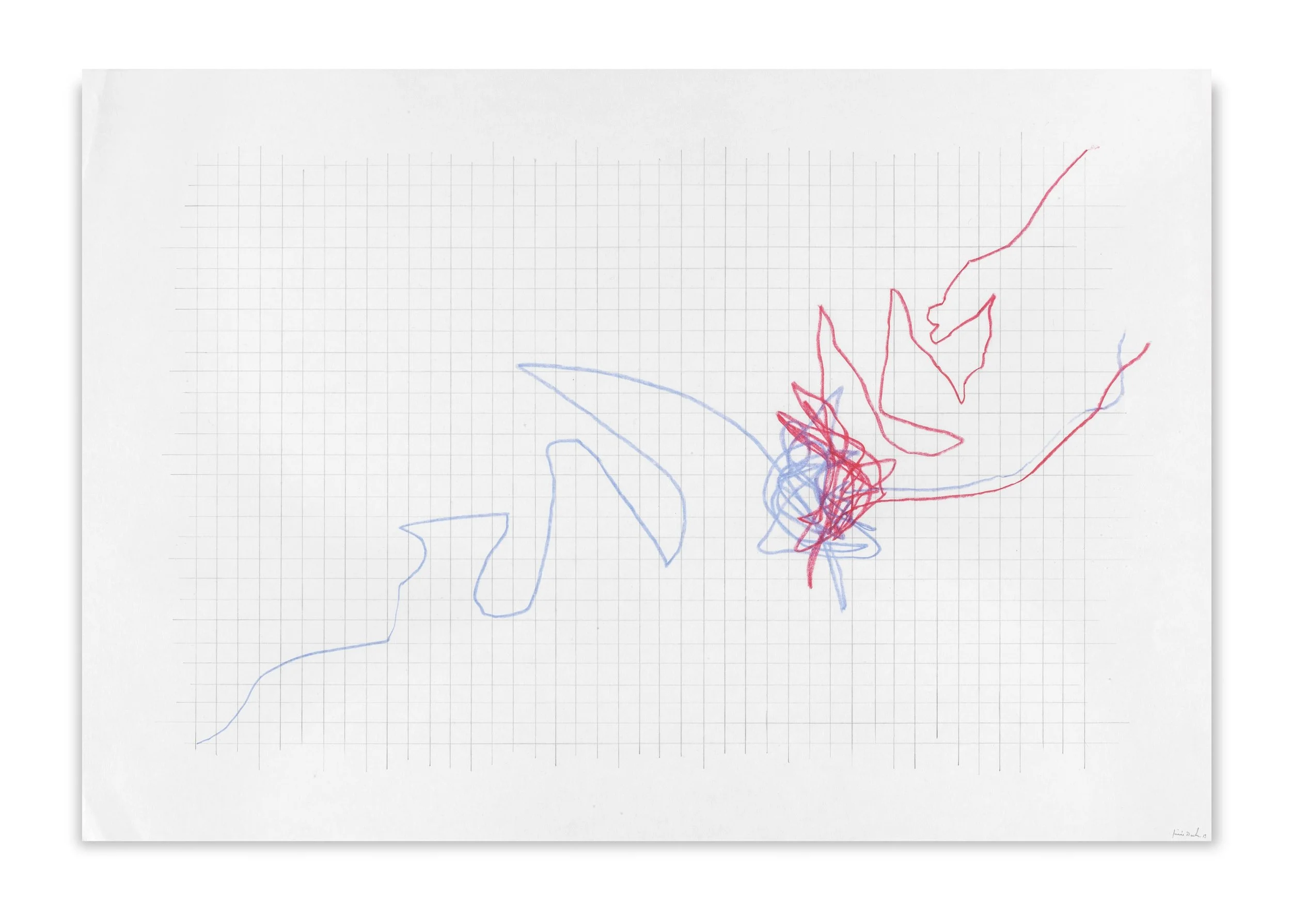

In Untitled, 2013, eleven graph-like drawings act as a parody of statistical analysis – consistent with Durham quoting the architect Yona Friedman as follows: ‘The statistical method is the main tool of science today. But statistics only provide correct answers to irrelevant questions.’ Accordingly, On a Scale of One Through Ten turns out to deal with fish scales; and other titles of individual drawings include Recalcitrant Trends, The Turquoise Line is Probably Indicative, Not Everything Functions, and More a Process Than a Beginning and an End. And one could take that resisting of interpretation, too, as a play on art – on how meaning is read into abstract marks.

For more information on Jimmie Durham and his work, please visit: https://barbarawien.de/artist.php?artist=9

NUMERO CROMATICO: ‘MY DESIRE MY DREAM MY DESPAIR’ AT AOA;87

Rome-based collective Numero Cromatico – chromatic number – has a shifting membership of up to twenty. They describe themselves as ‘an artist, a research centre and a publisher composed of researchers from various disciplines, from the arts to neuroscience’. As such, they aim to merge visual arts, design, architecture, and literature with scientific knowledge—including neuroaesthetics, empirical aesthetics, experimental psychology, and digital studies. The collective aims, says the gallery, ‘to reimagine new forms of relationships between humans, nature, and technology while challenging the paradigms of contemporary society’. Since 2011, Numero Cromatico has fostered the debate on the relationship between art and neuroscience through Nodes – a journal of art and neuroscience.

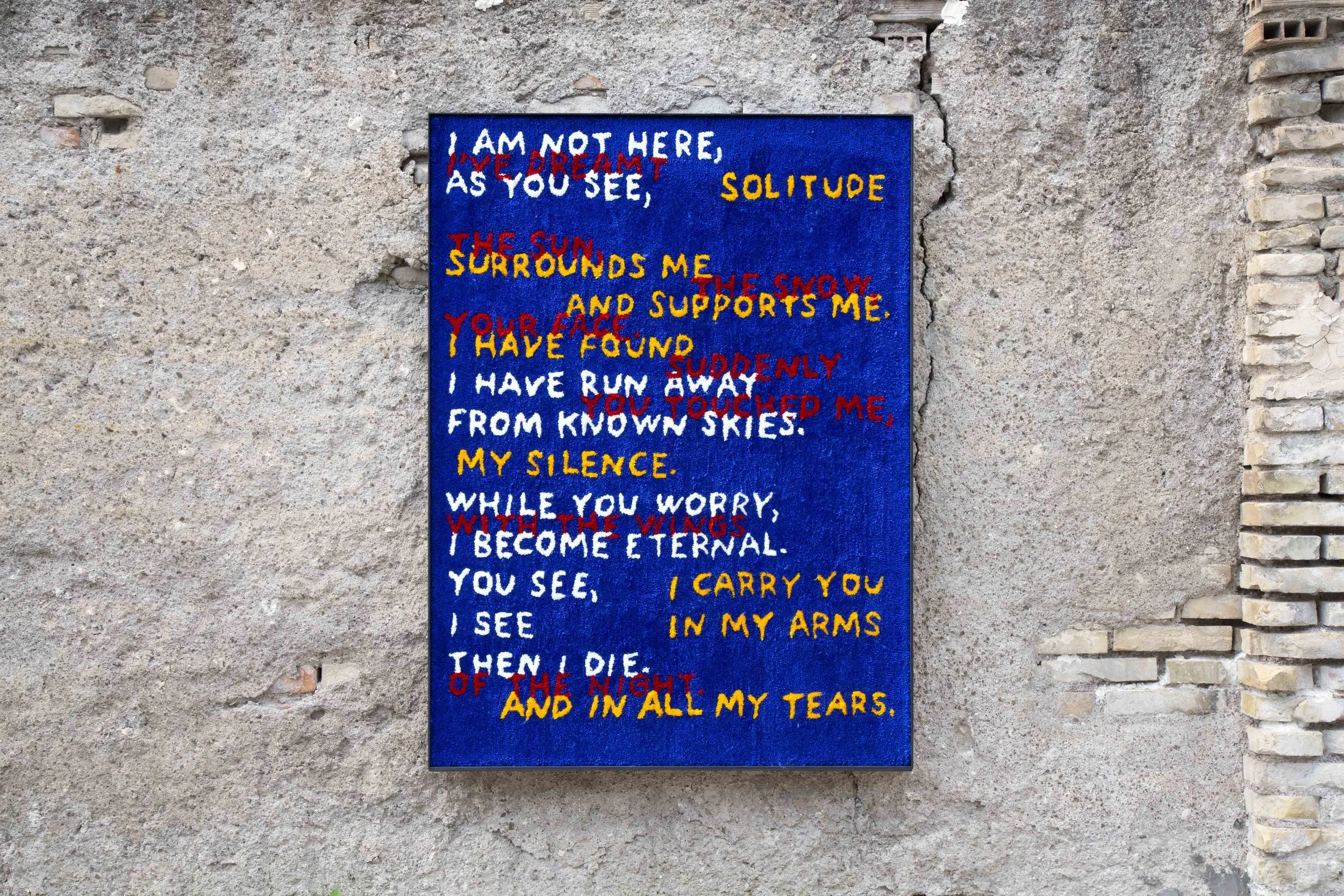

Their exhibition at AOA;87 included neon works highlighting phrases, and tapestries with poems – also available as prints. Both emerge from custom-built AIs. The poem works are the most sophisticated. Each use three colours for the lettering, and each colour corresponds to the input of a separate custom-built AI: one trained on the collective’s choices of poems about ‘love’, one on poems about ‘the future’, and one on poems about ‘the end’. The results are worryingly plausible, as you can test by reading through in each given colour. Moreover, you can also read the words regardless of colour, producing less predictable and oddly compelling conjunctions.

To take an example, ‘I am not here, as you see’ incorporates single-colour readings starting ‘I am not here, / as you see, / I have run away / from known skies. / While you worry, / I become eternal’ and ‘I’ve dreamt the sun, / the snow, / your face. / Suddenly / you touched me / with the wings of the night’ and ‘Solitude / surrounds me / and supports me. / I have found / my silence’. All of which also allows the cross-reading ‘I am not here, / I’ve dreamt / as you see, solitude. / The sun surrounds me / the snow / and supports me. / Your face / I have found. / Suddenly / I have run away. / You touched me / from known skies, / my silence while you worry / with the wings’.

Does all this amount to meaning or pseudo-meaning? That depends on whether you hold that an artificial intelligence might do anything that counts as demonstrating thinking or consciousness. That’s a matter of ongoing and current controversy as the power of computing increases. Much of the debate has centred on two seminal arguments. The Turing Test, famously introduced by Alan Turing in 1950, aims to show that there is no reason in principle why a computer cannot think. Thirty years later, John Searle published a paper claiming that even a computer which passed the Turing Test could not genuinely be said to think. ‘The reason that no computer can ever be a mind’, says Searle, ‘is simply that a computer program is only syntactical, and minds are more than syntactical. Minds are semantic, in the sense that they have more than a formal structure, they have a content’ and ‘thinking is more than just a matter of manipulating meaningless symbols, it involves meaningful semantic contents. These semantic contents are what we mean by ‘meaning’. It doesn’t matter, says Searle, how powerful the computer is, as ‘if it really is a computer, its operations have to be defined syntactically, whereas consciousness, thoughts, feelings, emotions, and all the rest of it involve more than a syntax. Those features, by definition, the computer is unable to duplicate however powerful may be its ability to simulate.’ Just as, says Searle, a computer simulation of a rain storm will not leave us wet – and no one believes it will – a computer simulation of mental processes won’t actually involve thinking.

There are various counter-arguments to Searle’s claim, but the argument cannot be said to have been refuted. Perhaps few would cite the generation of poems in the manner of Numero Cromatico’s experiments as evidence that computer are thinking poetically, but it is an interesting step along the possible way.

For more information on Numero Cromatico and their work, please visit: https://www.numerocromatico.com/en/

ALFREDO JAAR: ‘THE END OF THE WORLD’ AT KINDL — CENTRE FOR CONTEMPORARY ART

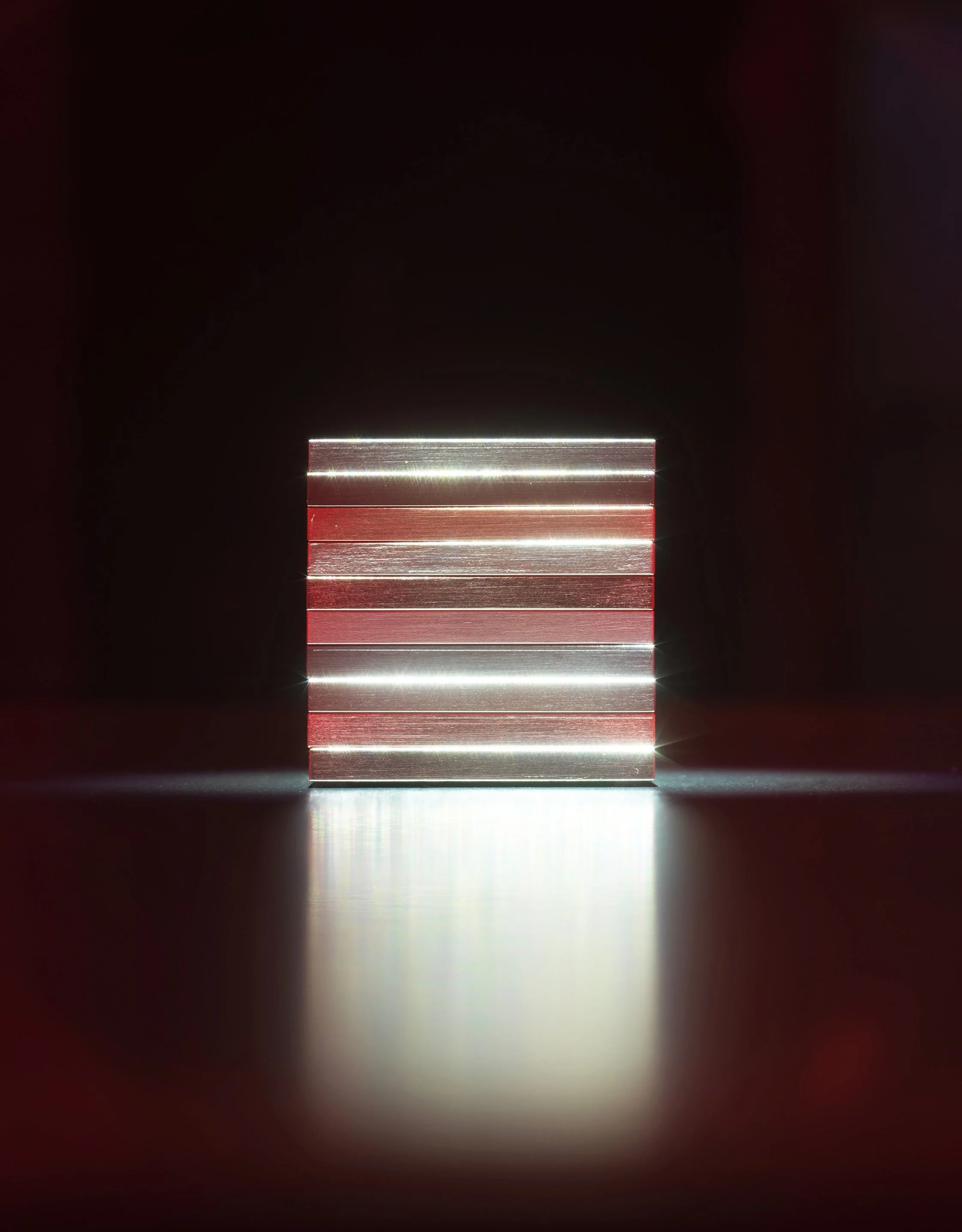

Each year, the KINDL – Centre for Contemporary Art invites a prominent artist to create a site-specific installation for its Kesselhaus: a 20 x 20 x 20 metre cube with unrenovated walls that make its industrial past obvious. Alfredo Jaar, the Chilean-born artist and filmmaker based in the US, presents just a 4 x 4 x 4 centimetre cube in the middle of this vast space, lit by an eerily red light. Jaar is known for public interventions and installations that challenge viewers to confront uncomfortable truths about human rights, conflict and power structures.

Since the mid-1980s, he has been investigating the theme of resource greed and its consequences, and here he reflects on the long-term effects of large-scale mining of metals. Following years of research supported by human geographer and political geologist Adam Bobbette, Jaar demands we focus on the small cube composed of layered raw materials: cobalt, rare earths, copper, tin, nickel, lithium, manganese, coltan, germanium, and platinum. They are ten strategic metals vital to digitalisation, electromobility, high-tech applications, and storage media – including in the military sector, where they underpin the functionality of modern weapons systems. The extraction of these materials is fraught with severe human rights violations and environmental destruction: the exhibition booklet sets out the details metal by metal in ten essays by Bobbette. The provocatively apocalyptic title anticipates scenarios of future resource wars.

Jaar’s point, then, is to set the almost absurd diminutiveness of the cube against the immense scale of both the Kesselhaus and the ecological, social, and political upheavals it represents. It took three years to compile the cube. Could he have faked it? Perhaps, but says Jaar, ‘I had an almost spiritual need to make it the real thing. Each mineral is there, sometimes 100% pure, sometimes mixed with another metal to achieve the right shape.’ Often, he couldn’t obtain it in the amounts he wanted, so he had to buy more: ‘people thought we were crazy: ‘What are you going to do with 200 grams of lithium?’ He tried to ‘make it so minimal that the emptiness, the silence and the red light give that little cube gravitas. If you were to show the same cube in a normal gallery space with regular light, it becomes an object’.

Bobbette identifies an irony in the history of mining: in the 20th century that was dominated by colonial activity, and by the drivers of the industrialisation that produced the carbon critically impacting on the world’s climate. Now ‘we are living through another industrial revolution, a traumatic re-enactment of the past where geopolitical plate tectonics are shifting; and … conflicts are flaring to build renewable technologies’. Those technologies are fundamentally digital. ‘Every solar panel, wind turbine, and electric vehicle is connected to computers. Every computer is a collection of chips, cables, satellites, and screens made of stuff from a mine.’ Consequently ‘net zero is impossible without the ten minerals in this exhibition … The extraction of each is the end of the world.’

Take Cobalt as an example. It is found in the Earth's crust almost entirely in a chemically combined form: the free element, produced by reductive smelting, is typically a by-product of copper and nickel mining, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) yields most of the global supply – 80% of the 300,000 tons produced in 2024. Cobalt, says Bobbette, ‘is poisonous, it kills miners. It was called the Black Devil in the 16th century. Today, it kills the children who mine it in Congo. China and the United States are in a mineral arms race for it. Sixty percent of all cobalt goes into rechargeable batteries. A standard electric vehicle uses about ten kilograms … Most African cobalt mines finance civil wars where miners are neither allowed to properly live or die; they handle cobalt with their hands, slowly poisoning themselves to pay for food’. Prospecting continues for alternative supplies, given that Congo’s reserves are likely to be exhausted, and ‘western states are securing their critical mineral supply by militarizing mining concessions with private contractors and creating exclusion zones the size of megacities’. Bobbette cites comparable stories associated with the other nine ‘critical minerals’.

The cumulative effect is to point out that, while we may feel we’re doing the right thing by changing to lithium batteries and driving electric cars, that comes at the expense of countries from the Global South and the habitats of indigenous communities. Not that Jaar is proposing a way forward. In his words: ‘the only answer possible to this is a truly radical lifestyle change. And I don’t think we’re capable of that. I cannot see how it’s possible. So that’s why I don’t see light at the end of the tunnel. It is our children who will suffer the consequences … I’ve never seen things as dark as I see them now. And this is from someone who witnessed the genocide in Rwanda, surrounded by corpses rotting in the sun.’ No wonder it has been said of Jaar that ‘human misery is his profession’.

For more information on Alfredo Jaar and his work, please visit: https://alfredojaar.net/

All images shown courtesy the artist, gallery, and photographer © Various — details as above.