PETER MATTHEWS: A PAINTER SHIFTED BY MARINE BIOLOGY

Normally, Peter Matthews has an unusually isolated practice. He is known for paintings made on remote coasts when, in his words ‘the materials will double up as a shelter of some kind, from the weather like a sun screen; from the rain such as a roof; or a resting platform, like a hammock - so I have got used to working on large spreads of unprimed canvas that allow me to be flexible and responsive to the environment.’ Sometimes he’ll dive to the bottom of the ocean with a canvas, barely able to see what he’s doing. And his drawings can also be made underwater so that, as he puts it, ‘the sea is depicting the sea itself’. Shells, sand, and litter may find their way onto his paintings as he records what he experiences in a stream-of-consciousness manner. Sometimes, as in ‘Summer Sequoia’, 2019 – made either side of the Pacific in Japan and the USA – Matthews combines two canvases made on two coasts to suggest the journey and distance between them.

How would that practice change if Matthews worked not only in a busier area in which people are always in view, but also in collaboration with a scientist with a shared interest in the sea? The answer, revealed in his show at the Glyn Vivian Gallery in Swansea, proves an unusually subtle example of how science can influence art. That may be, in part, because Matthews declares an aversion to ‘the cliché of artist making pictures of what the scientist works with’. Rather, he feels that the German marine biologist, Ruth Callaway, changed how he went about things. Perhaps that’s why, as it turns out, Matthews’ usual painting and drawing doesn’t feature much. Instead, sculptural installation and performative film dominate ‘Grounded’ – the show titled in recognition of the locked down circumstances of its making as well as its connection to the earth. Moreover, Matthews also lured Callaway into contributing to the art.

Matthews says Callaway informed his thinking as they walked out onto the Swansea Bay – a group of beaches forming part of the Bristol Channel, which has the second greatest tidal range in the world. She introduced him to how that massive tidal range exposes large parts of the seafloor for a few hours each day, allowing her to carry out her passionate and detailed research with the reef-forming worms that live there and what we can learn from them. The worms bio-engineer their own reef from the surrounding sand, and perhaps there was a direct echo of that in ‘9 Islands’, an action documented by photographs. We see Matthews building a set of sand islands.

He thinks Covid-19 played a part too, given how it has made ‘everyone self-aware of their own bubble of space’. Matthews was claiming his own territory – in a humorous vein, given that the islands would soon be enveloped by the rising sea; but not without a serious undercurrent if we read across to rising sea levels. Matthews mentions, though, that Callaway explained in conversation that rising sea levels aren’t such a simple matter of extra water from melting ice as is commonly assumed. Since the end of the ice age, that has been partly offset by ‘post-glacial rebound’: as glaciers melt, the weight that pushes down the landmass reduces, and the land rises. However, the net effect is still that sea levels are increasing. Yet, Matthews declares himself somewhat ambivalent anyway: he mentions the ice ages, likely caused by the dust and debris from meteorites or volcanoes blocking out the sun, as parallels of a sort, and points out that ‘in the grand scheme of the history of the earth, humanity is just a stone in the pond.’

Matthews links his recent sculptures, mostly made from items found on the beach, to how Callaway explored the bay with him: she would go with a specific purpose, whereas he had previously been more aimless, open to inspiration rather than seeking it. ‘Every time I went out in the bay with her’, he explains, ‘she would be getting down onto the microcosm of the world, where I was previously drifting at the macro level.’ Matthews has always liked the unexpected aspect of found items – as when he has incorporated them in paintings - but now found himself seeking them out more systematically in the focused way of a biologist hunting down worms. ‘Entrance to Another Side’ is a door which was being thrown out from a B&B being gutted: Matthews sawed it off to fit it in his car, then painted it in a shade appropriately known as ‘submarine yellow’ to cheer it up. He says the work ‘summed up for me the whole experience of working with a scientist … There’s acquiring scientific knowledge about particular species or landscapes – scientific matters which I like to play with, even if I don’t really understand them – but also a more subjective, human side – a sense of perceptions changing, like going through a door. I was curious about what is beyond the door.’

‘Swansea Bay is a Little Darker Tonight’ started from Matthews finding a big plastic bag full of bulbs. Attracted by them, he then began asking people for old bulbs. He ended up with a jumble of the variety of shapes and types which is the modern trend, and added a title which playfully references another environmental consideration: light pollution. ‘Off Course’ consists of a sailboat tiller and rudder mounted as if, rather than cutting through the sea, it is about to cut through a wall. Matthews felt an animism in this found object, stemming from the history of its movement through water. And, he says, ‘showing part only of the whole encourages contemplation of what is not there, of the present and the absent’.

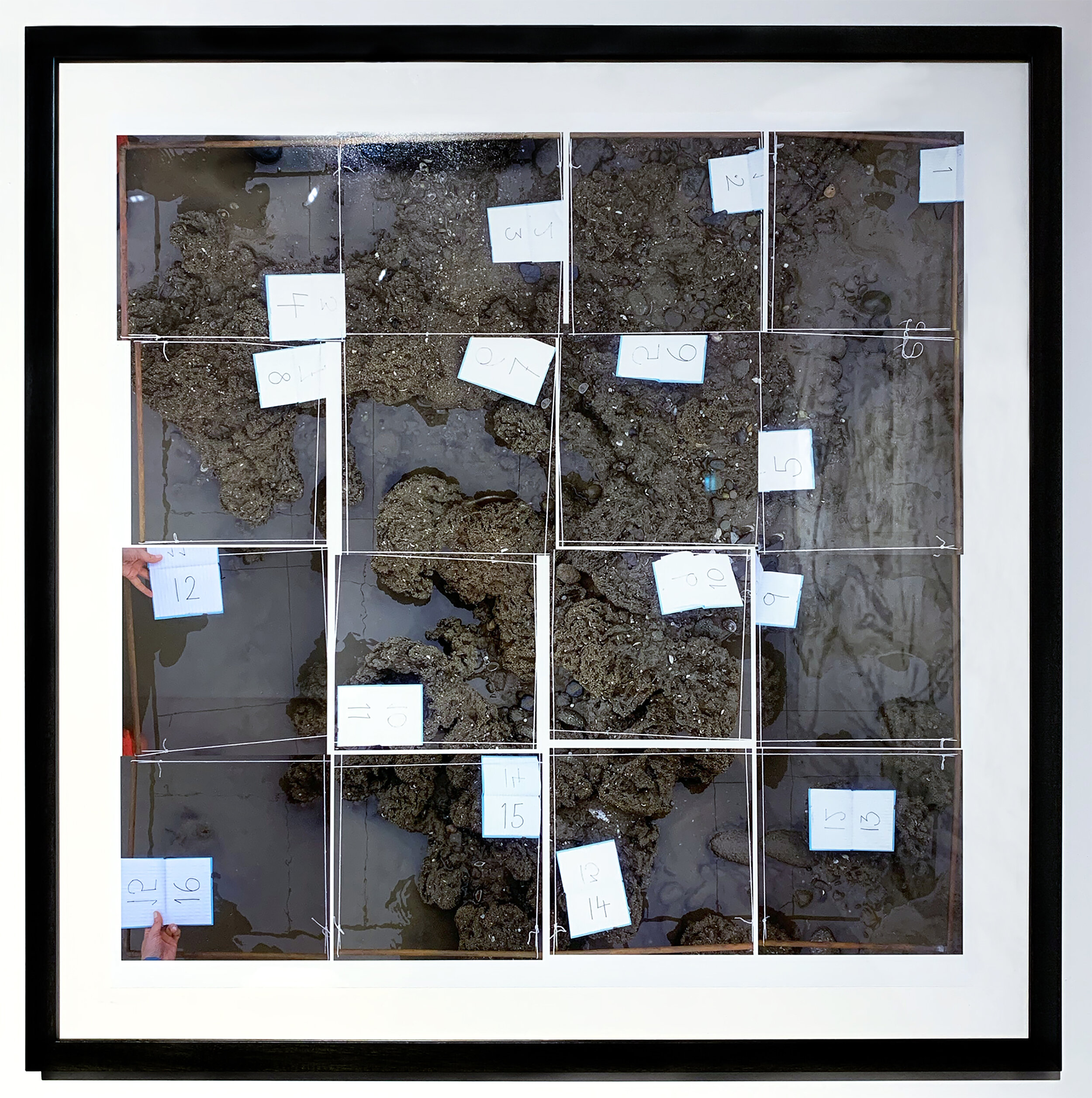

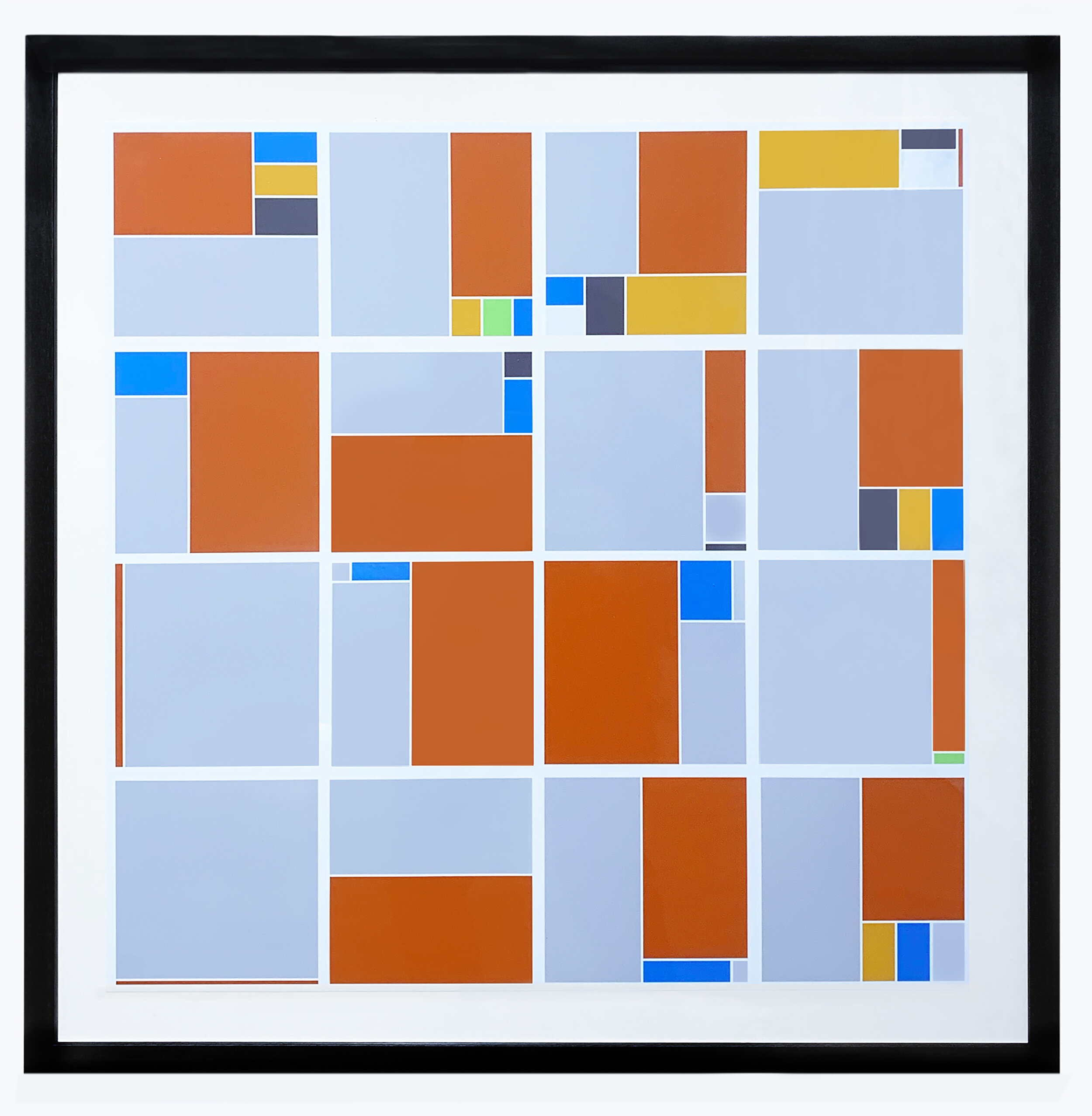

The exhibition shows the influence flowing, not just from Callaway to Matthews, but also the other way round. Callaway has contributed four works – ‘Research Findings’ – inspired by the outings the pair took together. They emerged from Callaway’s use of a two-metre copper sampling quadrant, an object found by Matthews, though used at a smaller scale by scientists. The quadrant, carried across the inter-tidal area, is able to frame something ordinarily less visible: ‘rather’, says Matthews, ‘as good photographers frame the world and make us see what is really there.’ Callaway used the device to highlight matters of interest then combined photographs of those sites into collages showing the forms made by reef worm forms, as visible at low tide on Swansea Bay.

Matthews repurposed the quadrant for the sculpture, ‘Contact’, where it contains a jostle of clay balls – alluding to the reduced social contact of human clay at present. Callaway also took part in another meditation on human clay: for ‘Duality’, Mathews had them both throw ten pieces of clay across the gallery at paper affixed to found sheets of wood on the wall, enabling the different outcomes – artist’s versus scientist’s – to be displayed side by side. Callaway was evidently game but, says Matthews, ‘wondering why she was doing it’, and her more hesitant actions are apparent in the result. Callaway herself says that ‘working with Peter Matthews during his fellowship forced me to take a step back and look at my work from a different direction. The questions of purpose, scale, and also societal relevance came much more into focus.’

Matthews has often made films before – typically with a drone, using the camera to follow the process as he paints by the ocean. He exhibits them alongside the results ‘not because I’m interested in showing myself, but because I can use film to add to the whole painting – I don’t see them as separate.’ In Swansea Bay, though, he made films ‘with their own film hat on, rather than a painting hat’. He explains them as contrasting responses to the inspiration provided by Callaway’s approach.

‘What Goes Up Must Come Down’ might be seen as responding to the scientific context by being, light-heartedly, as unscientific as possible. It shows five minutes of Matthews attempting – and mostly failing – to shoot a basketball through hoops he has set up on the beach. He saw this as ‘a space and time to just simply be: be with the earth, be the forces of nature, be alone, have a live dialogue with something beyond myself, something real, tangible, and new. These live exercises with chance, probability, distance, letting go, scoring, missing, learning, adapting, coming closer to something, of dreams and visions, reality and the surreal, capture how I feel going through this historical time we live through now.’ But, he also saw himself as upending Ruth’s rigour ‘by doing something completely nonsensical – an exercise in futility and complete chance.’ It was an escape from reality into a parallel world, but one from which ‘you know you’ll always come back’.

‘Rewind’, on the other hand, is in empathy with the science. We see Matthews, in footage which runs backwards, walking through the sand to unmake, as it seems, a series of spirals. The shape often recurs in the natural world - ‘in our blood, our circulation, water and air’, says Matthews, by way of examples, ‘much of the natural world begins and ends in spirals. But so do pagan ritualistic practices – when a spiral represents healing, rejuvenation and recovery. That put me in mind of seeing the news and thinking – if only we could go back to where we were.’ Reversing the film enables that, or at least a suggestion of it. ‘Rewind’ is also typical of his wider practice in that a durational time-based process – like drawing or painting – is set up in space so that ‘through time there’s a meandering with your own self.’

To make ‘Rewind’ Matthews was, in effect, drawing in the sand – albeit the result was an ephemeral one which we see disappearing on film, just as it soon did with the incoming tide. And there are two other unusual drawings in the show, both called ‘Porphyra’ after the seaweed they include. It’s very common on Swansea Bay, and widely sold locally like a lettuce of the sea. Matthews placed the leaves on copper leaf as a way to add a mystical, icon-like aspect to the visual language – noting that copper also has, at least conceptually, good antibiotic qualities which might help keep you safer in a pandemic. The copper yielded, he says, ‘a quality of light consistent with how I felt out on the bay’ and a ‘fractured or fragmented abstract composition consistent with not knowing where we are in life’. He felt how ‘everything is being shifted’, and connected that to the notion of a ‘shifting baseline’ which Callaway had mentioned in a scientific context. Are we using the right, consistent starting point for comparisons? Or has the baseline shifted?

That’s an appropriate way to conclude: for what emerges most strongly from this collaboration between artist and scientist is not so much the direct transfer of any particular data or theory, or even subject from marine biology to Matthews’ latest work, so much as a sense of how the approaches of scientist and artist provide different baselines from which to measure and understand the world. Looking at the example of Matthews and Callaway emphasises the mutual advantage of each being grounded in each other’s practice, as well as their own.

‘Grounded’ is currently installed at the Glyn Vivian Gallery, Swansea (post-lockdown viewing details not yet known), and is one of eight artists in ‘From Nature’ at informality, Henley on Thames (18 Feb – 18 April).

References

Bilker-Koivula, M., Mäkinen, J., Ruotsalainen, H. et al. Forty-three years of absolute gravity observations of the Fennoscandian postglacial rebound in Finland. J Geod 95, 24 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-020-01470-9

All images and video shown courtesy of © 2021 Peter Matthews