LUKE JERRAM: SUBLIMELY INFORMATIVE

Portrait of the artist with Museum of the Moon. Photo credit: Luke Jerram

Since 2004 Luke Jerram has been producing, exhibiting and photographing intensively-researched glass models derived from the microbiological structure of bacteria and viruses - 30 so far, the latest being the coronavirus. The series arose from him seeing media representations that were coloured when, in fact, viruses are colourless. That’s because they are smaller than the wavelength of light - so small they can only be seen under an electron microscope as quite undefined grainy images. Jerram’s work considers how the artificial colouring of scientific microbiological imagery affects our understanding of these phenomena, moving beyond both convention and normal observation to seek an underlying truth.

He has received letters such as one from an HIV sufferer saying that his sculpture ‘has made HIV much more real for me than any photo or illustration I’ve ever seen. It’s a very odd feeling seeing my enemy, and the eventual likely cause of my death, and finding it so beautiful’.

As such, Jerram’s glass artworks improve public understanding. ‘Scientists have to communicate with the public’, says Jerram, ‘and it’s a useful way to inspire the next generation’. He considers such engagement with science to be ‘really important, as many of today’s major changes in society stem from advancement in science and technology. It is quite natural for artists to reflect that.’ The glassworks are also valued within the scientific community: photographs of them feature in medical journals and virology text books. Jerram works in partnership with scientific institutions to develop new microbes for the series, including for his most recent model: the coronavirus, commissioned by Duke University inAmerica in January 2020, just after it was identified in China. By the time the edition of fivewas sold to the benefit of Médecins Sans Frontières, it had become clear how significant its subject would prove.

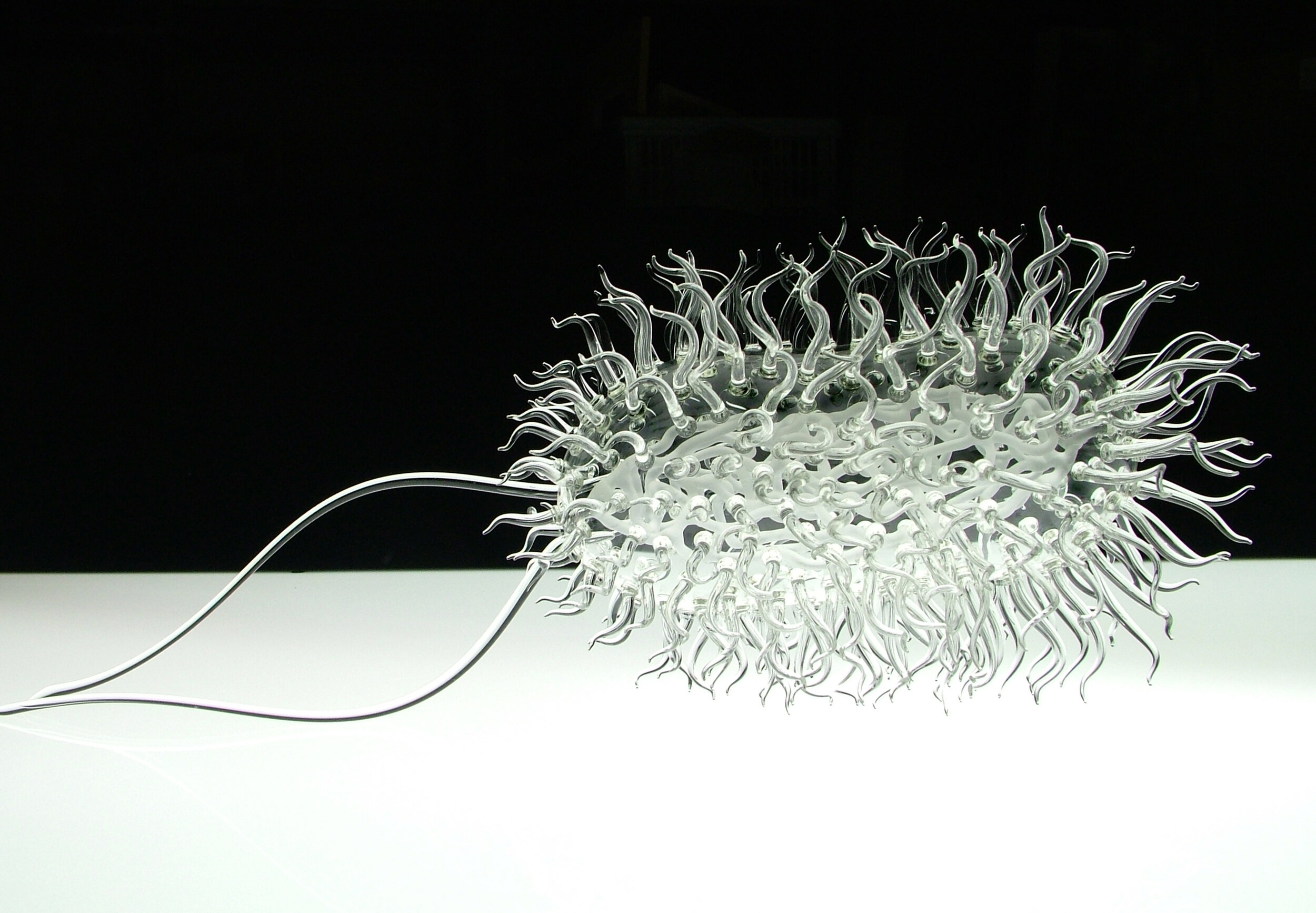

Malaria Glass Microbiology Sculpture by Luke Jerram

As art, the Glass Microbiology provides an initial experience of looking at delicately beautiful and apparently abstract sculptures. Once the viewer is lured in, however, they turn out to combine - rather elegantly - three well-established art tactics: sinister beauty, scale shift, and the operation of uncontrollable processes to generate abstraction. The tension between attraction and repulsion is a major part of Jerram’s interest – and the sinister side of beauty, along with the deadly aspect of fragility, is prominent once we know that the sculptures represent lethal viruses. Jerram’s first subject was HIV, and Malaria, Ebola and Swine Flu were among those preceding Covid-19. Jerram, incidentally, picked up swine flu in the course of that project – but hasn’t yet had coronavirus.

Artists have often increased the size of objects in order to make us look at them afresh and extend what we can perceive – indeed, Jerram shows us something we could not normally see at all. The Glass Microbiology works are a million times larger than their subjects. Moreover, in 2015 Jerram made an inflatable model of E. coli, which – at 28 metres long - was five million times life size. Many artists have also sought to distance their own subjective decisions from the generation of thework, once they have set in motion the underlying conditions for its production. The look of Jerram’s work is driven by evolutionary contingencies of nature, and so, while the artist might adapt these to some extent – in consultation with the virologists he often works with,who sign off the technical drawings – he has, in essence, set the conditions of million-fold scale and the absence of colour (or, rather, refusal to add colour), then ceded control of the particular aesthetic result. That is determined by the scientific structure of the chosen virus, the limitations of glassblowing and the expertise of the glassblowers he recruits.

HIV Glass Microbiology Sculpture by Luke Jerram

E.coli Glass Microbiology Sculpture by Luke Jerram

Glass Microbiology is just one of some 60 major projects Jerram has produced in a wide-ranging practice which originated in sculpture and performance and ranges across music, the environment, perception and participation as well as taking a particular interest in science. Indeed, there’s another Covid-19 connection through the currently-touring In Memoriam, 2020: an open air field of red and white flags created from bed sheets and arranged in the form of a medical logo, commemorating both the victims of coronavirus and the health workers who have done so much to minimise their numbers. People can walk between the wind-blown flags – and the public often have a prominent role to play.

In Memoriam artwork by Luke Jerram. Photo credit: Sigrid Spinnox

Earlier projects include Withdrawn, 2014, which placed fishing boats in woods outside Jerram’s home city of Bristol – as sculptural objects, sites for performances and harbingers of rising sea levels; Sky Orchestra (from 2003 onwards), in which seven hot air balloons with speakers attached create a vast surround-sound experience to test out scientific findings on the influence of music on sleep; and the three-week public presence of 2000 pianos in 70 cities for the ongoing Play Me, I’m Yours, in which the piano acts as a catalyst for people to talk to each other and exhibit public behaviours which vary considerably across the world. As that sample indicates, Jerram’s work is very much driven by ideas, the artist’s role being to organise the complicated process of making them a reality.

Museum of the Moon artwork by Luke Jerram. Photo credit: James Billings

Another stream of work which directly combines art with scientific education is of hanging globe forms representing Moon, Earth and Mars, each about seven metres in diameter and accompanied by specially commissioned soundtracks (they look very substantial but are actually just balloons with a light inside). These, too, indicate Jerram’s interest in perception of scale – how we feel when confronted by objects of altered size – and in extending perception to allow people to get a closer look. In the case of the moon, people are able to look at the far side, which is quite different from the side we routinely see. Jerram explains that seven metres is ‘a good scale to generate impact compared with that of the human body, and it also works both outside and inside. I have just made a ten metre earth for the Olympic swimming pool in Beijing, but there just aren’t generally many indoor spaces available to show the artwork of that size. Seven metres is the minimum size to generate awe while remaining practical.’ That sizing leads to a moon at 1:500,000, earth at 1:1,800,000 and Mars at 1:1,100,000 - effectively a reversal of the scale shift in the microbiology project.

Museum of the Moon artwork by Luke Jerram. Photo credit: Ed Simmons

There are several touring versions of the Museum of the Moon (2016): they’ve been visited by over ten million people. It’s often shown in cathedrals: sometimes that’s the only practical option, but Jerram likes the architectural setting. It also leads to a nice balance, as the moon is associated historically with both pagan rituals and the Virgin Mary – though ‘when the telescope was invented’, says Jerram, ‘and people realised that the moon wasn’t a perfect orb, but craggy and pitted and imperfect - it was dissociated from Mary. So I like the idea of bringing it back into the cathedral.’ Jerram goes on to note that ‘the moon has always inspired humanity, acting as a ‘cultural mirror’ to society, reflecting the ideas and beliefs of all people around the world. Over the centuries, the moon has been interpreted as a god and as a planet…. Different cultures around the world have their own historical, cultural, scientific and religious relationships to the moon. And yet somehow, despite these differences, the moon connects us all.’ As with all three globe works, Jerram encourages appropriately themed events and local research at each location, so that new stories and meanings arecollected and compared from one presentation to the next. The Museum of the Moon is currently touring and will be on view next in Bristol and Durham cathedrals.

If the 17th century development of the telescope marked a turning point in humanity’s perception of the moon, the comparable point for Earth was just 50 years ago. Prior to NASA’s Apollo 8 mission in 1968, grainy black and white images were all that was available, explains Jerram, and they had little emotional impact. ‘People didn’t know what colour the earth was – the extent and nature of its blueness was a revelation.’ Seeing that became a catalyst for the environmental movement, triggering what has been termed the ‘Overview effect’. Common features of the experience for astronauts, says Jerram, ‘are a feeling of awe for the planet, a profound understanding of the interconnection of all life, and a renewed sense of responsibility for taking care of the environment.’

Gaia artwork by Luke Jerram. Photo credit: Ben Foster

His artwork Gaia aims to evoke the effect through an internally lit sculpture in which each centimetre describes 18km of the Earth’s surface. ‘By standing 211 metres away from the artwork’, he notes, ‘the public cansee the Earth as it appears from the moon.’ During October Gaia (2018) can be seen in Gloucester Cathedral, where the Museum of the Moon has already been shown. Jerram says that he prefer to put the Earth in a cathedral only if the moon has preceded it, so the local public have a wider understanding of his projects. Otherwise, given that those early images of the earth from space became a symbol of evangelical Christianity, he fears that Gaia is too likely to be seen in narrowly religious terms in that setting. Jerram prefers the primary message to be that Earth is ‘an incredibly beautiful and precious place. An ecosystem we urgently need to look after – our only home. Halfway through the Earth’s sixth mass extinction’ – the first for 65m years – ‘we urgently need to wake up, and change our behaviour.’

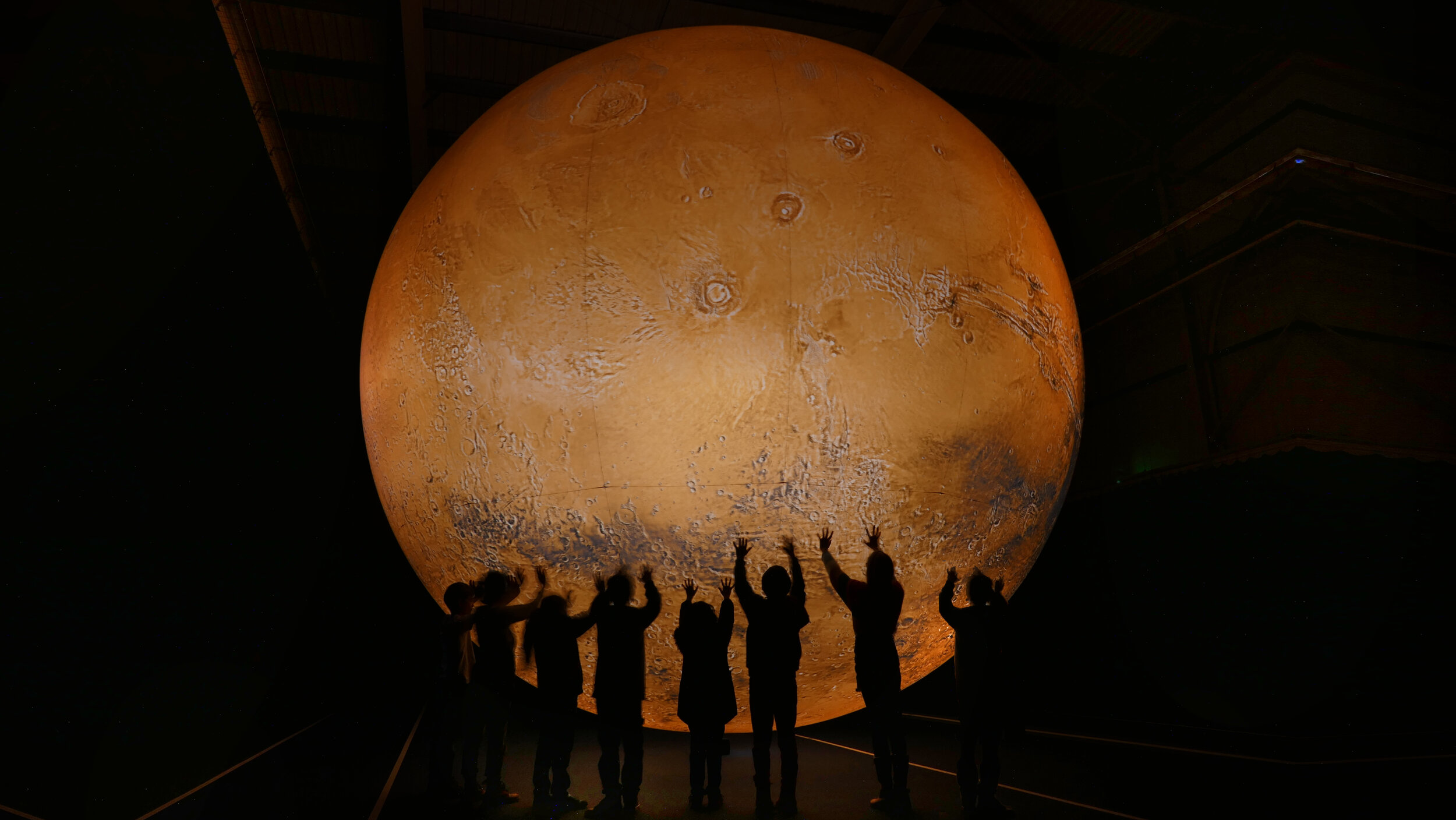

The more recent Mars (2020) is only just beginning to tour. It doesn’t conceptually fit in with cathedrals, says Jerram, and so it will be seen mainly in science museums. Similarly created from high resolution NASA data, this will offer a chance to study the surface of the planet upclose.

Mars by Luke Jerram

Over the coming months Jerram will be researching humanity’s historical relationship with Mars, drawing out the stories, myths and beliefs to present back to the public. No doubt it will provoke wonder comparable to the Moon and Earth.

People find it amazing to ‘be in the same room’ as the moon; children have sought reassurance from Jerram that he will return the moon to the sky after borrowing it; and Jerram recalls that he has heard a young man bringing his girlfriend saying ‘Let me take you to the moon and back’. The film documenting Gaia includes emotional and even tearful responses.

Luke Jerram, then, has found engaging ways to combine the transformative aspects of art with the clarity required of public education. The works discussed also tap into our cultural heritage and our sense of the ‘romantic sublime’ - of the limitless or incomprehensible aspects of the natural world inspiring awe at what is beyond and greater than ourselves. Moreover, the new perceptions generated have the potential to affect our attitudes and actions in such areas as medicine and climate change: this is art that can make a difference.

Swine Flu and artist.

All images and videos courtesy of © 2020 Luke Jerram